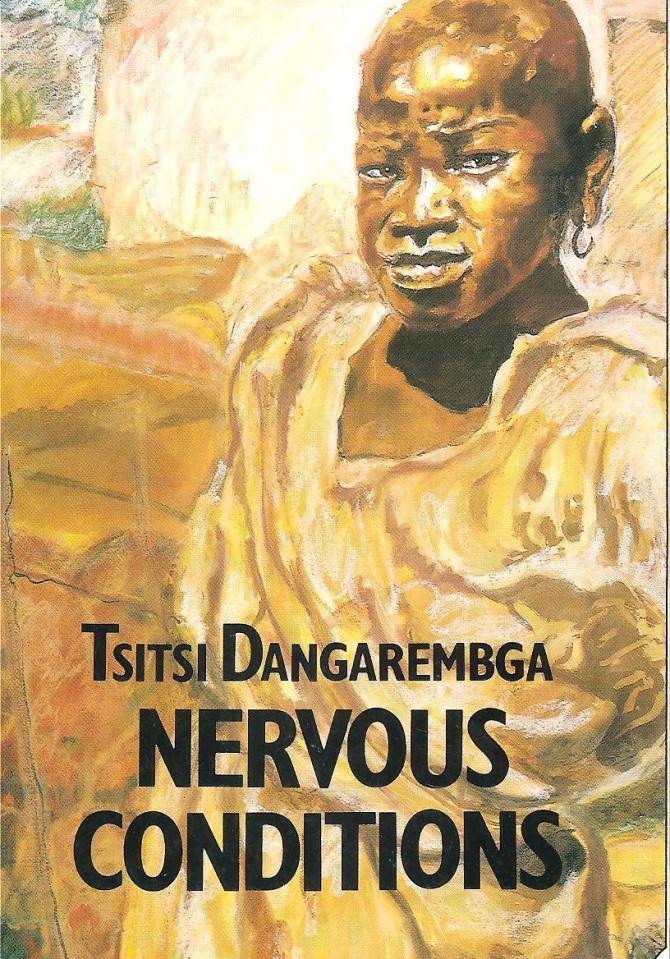

Literary Classics Revisited: ‘Nervous Conditions’ by Tsitsi Dangarembga

By Tola Ositelu

“‘This business of womanhood is a heavy burden’ she said ‘how could it not be? Aren’t we the ones who bear children? When it is like that…when there are sacrifices to be made, you are the one who has to make them. And these things are not easy; you have to start learning them…from a very early age. The earlier the better so that it is easy later on. Easy! As if it is ever easy. And these days it is worse, with the poverty of blackness on one side and the weight of womanhood on the other…What will help you, my child, is to learn to carry your burdens with strength…’

‘Nervous Conditions’ (page 16)

Impoverished Zimbabwean village girl Tambudzai is sick and tired of being treated like an inferior just because of her gender. Whilst her cocky older brother Nhamo has been plucked from the mire by their wealthy uncle Babamukuru and given a high quality education at his patron’s expense, she is expected to look after the homestead and farm with her beleaguered mother Mainini. Not so for Tambu. She manages to hustle some basic, if sporadic, schooling. Then, following the untimely death of Nhamo and she being the oldest surviving child with no other brothers to take up the academic mantle, her own fortunes change. She is invited to live with Babamukuru and his long-suffering wife Maiguru on the Protestant Mission where he is headmaster of a prestigious school for ‘natives’. Tambu gets the opportunity to fraternise with her estranged cousins Chido and Nyasha who spent their formative years studying in England. Both siblings seem to have been adversely affected by the experience in different ways.

Tambu is both fascinated and appalled by Nyasha’s worldliness and insatiable curiosity. Nyasha refuses to accept what is taken for granted as the societal norm. She is audacious and outspoken about any injustices and double standards she encounters, often putting her at odds with her uptight father. She is frustrated with her own mother’s excessive deference to Babamukuru. A brilliant academic in her own right, she has nevertheless side-lined her ambitions to preserve her husband’s self-regard. For all his good intentions, Babamukuru is imperious, lording his elevated status as the oldest-and most financially comfortable member of the family. Tambu’s father Jeremiah grovels away what is left of his self-respect and Mainini, still grieving her dead son and fearing she’ll lose her daughter to the same colonial influence that seems to have brainwashed her in-laws, grows more embittered with the years. As Tambu struggles to negotiate the culture shock of moving to the Mission and the seemingly infinite possibilities that come with this change of circumstance, her relationship with Nyasha deepens. However her cousin’s unrelenting introspection threatens to destabilise not just her world, but that of all those around her.

Author Dangarembga brings us a female-focused, 20th Century, Southern African answer to Chinua Achebe’s ‘Things Fall Apart’. An adult Tambu reflects on her journey from so-called peasant to educated, cosmopolitan woman but even with the benefit of hindsight, the bewilderment of those years stay with her. Her complicated but incredibly close relationship with Nyasha is the nucleus of the book:

‘…You could say that my relationship with Nyasha was my first love-affair, the first time that I grew to be fond of someone of whom I did not wholeheartedly approve…’ (Page 79)

Tambu admires her cousin immensely but is determined to avoid the psychological pitfalls that have beset Nyasha. It’s not so simple. Once exposed to the same uneasy cultural fusion living at the Mission, Tambu better understands why her cousin refers to herself as a hybrid. For those of mixed-heritage or second-generation immigrants like myself, this feeling of cultural ambiguity – with the blessings and curses it brings – is very familiar.

But this is not just any culture clash story. It’s that of the effects of colonialism felt on the African continent at a time when Independence movements and Pan-Africanist ideology swept across the motherland. Perhaps because it predates the recent glut of fish-out-of-water African immigrant stories of varying quality, there’s nothing derivative about it. It might be set in the 1960s long before Zimbabwe reclaimed independence but Tambu’s observations, hers and Nyasha’s internal struggles and the diverse ways they manifest, are as relevant as ever. Neither does Dangarembga write as if she has a western audience in mind, as pointed out by Kwame Anthony Appiah in his foreword. Localised terminology isn’t necessarily explained and the author doesn’t go out of her way to appease the European conscience. Nevertheless ‘Nervous Conditions’ has universal appeal. This is yet another exploration of the human condition conveyed with empathy without trying to manipulate a response from the reader. Two further factors help the novel transcend its immediate concerns. First it serves as a feminist clarion call:

‘…The victimisation, I saw, was universal. It didn’t depend on poverty, on lack of education or on tradition…Men took it everywhere with them. Even heroes like Babamukuru did it. And that was the problem. You had to admit Nyasha has no tact. You had to admit she was altogether too volatile and strong-willed. You couldn’t ignore…that she had no respect for [her father]…But what I didn’t like was the way all conflicts came back to this question of femaleness. Femaleness as opposed and inferior to maleness…’ (Page 118).

This is feminism at its most logical. It’s neither the uninviting sisterly solidarity that reeks of misandry nor the nebulous, makeshift sort that suggests shaking your booty somehow advances the cause. I could relate to Nyasha’s inquisitive, forthright nature. I could relate to how some of those around her would rather an assertive brown girl hold her peace and stay ‘in her place’. (I like to think I’m not as bloody-minded as Nyasha though). ‘Nervous Conditions’ presents many paradigms of strong but flawed women. There’s Maiguru who takes respecting her husband to an extreme that’s not beneficial for either of them. Babamukuru is answerable to no-one and she is a powder keg of suppressed dreams and unspoken opinions. Tambu’s aunt Lucia, on one hand, (apart from Nyasha) is the only woman bold enough to speak her mind regardless of what the (men)folk around her think. Then again, her inability to remain single for long means she indiscriminately takes up with unpromising suitors. Men dominate her world too; she just likes to believe she’s in control. That’s the thing with Dangarembga’s characters; no-one gets an easy ride. The men are pathetic, yes but the female contingent isn’t saintly either.

The other great weapon in the arsenal of ‘Nervous Conditions’ is its satire:

‘…The Whites on the mission were a special kind of white person…for they were holy. They had come not to take but to give. They were about God’s business here in darkest Africa. They had given up the comforts and security of their own homes to come and lighten our darkness. It was a big sacrifice that the missionaries made. It was a sacrifice that made us grateful to them, a sacrifice that made them superior not only to us but to those other Whites as well who were here for adventure and to help themselves to our emeralds. The missionaries’ self-denial and brotherly love did not go unrewarded. We treated them like minor deities. With the self-satisfied dignity that came naturally to white people in those days, they accepted this improving disguise…’ (Page 105)

Dangarembga’s sardonic wit helps to sugar the bitter pill of Tambu’s circumstances and the fact this is yet a microcosm of what was happening to her countrymen and women at the time. Moreover the effects are still being felt in Zimbabwe today.

Some writers only have one great book in them. Harper Lee well understood this. The eagerly anticipated follow-up to ‘Nervous Conditions’, entitled ‘The Book of Not’, despite being over a decade in the making, is a turgid mess. It beggars belief that the same author, so cogent and viciously witty in her first novel could produce something that it took all my started-so-I’ll-finish resolve to complete. Revisiting ‘Nervous Conditions’ has helped to eclipse the bad memory and remind me of Dangarembga at her best.