Notes from a Swedish Summer

By Nina N. Yeboah

One could spend an entire hour roaming the streets of Södermalm in search of a good pastry shop and come up empty. Darkened stores with door signs explaining the owner’s holiday or its abridged summer hours are not infrequent. Stockholm is a lazy city during the summer. The days are long; the weather can be warm and breezy. Everyone wants to enjoy the sun, whether home or abroad. I went to Stockholm with few expectations; I left enamoured by the quiet city.

A simple pleasure: navigating the city

Arlanda, which is the largest of the four airports serving Stockholm, is about 25 miles north of central Stockholm. For visitors heading to city centre, there are private transport options readily available but public transport is far less expensive. From the airport to city centre and throughout, I found public transport to be easily navigable. With little understanding of the Swedish language, maps and signage were still easy to understand. Stops are called and displayed on buses and trains. I was able to use a single weekly pass on buses, metro trains and regional trains.

Art & Public Space

Kulturhuset Stadsteatern

Whenever I venture somewhere new, I start a search for black communities and cultural productions. In Stockholm, I was led to the Baroque exhibit at Kulturhuset (on view until 19 October 2014). A mix of classic and contemporary art, the Baroque exhibit stretches its titular theme to bring together work of provocation, inquiry, and documentation.

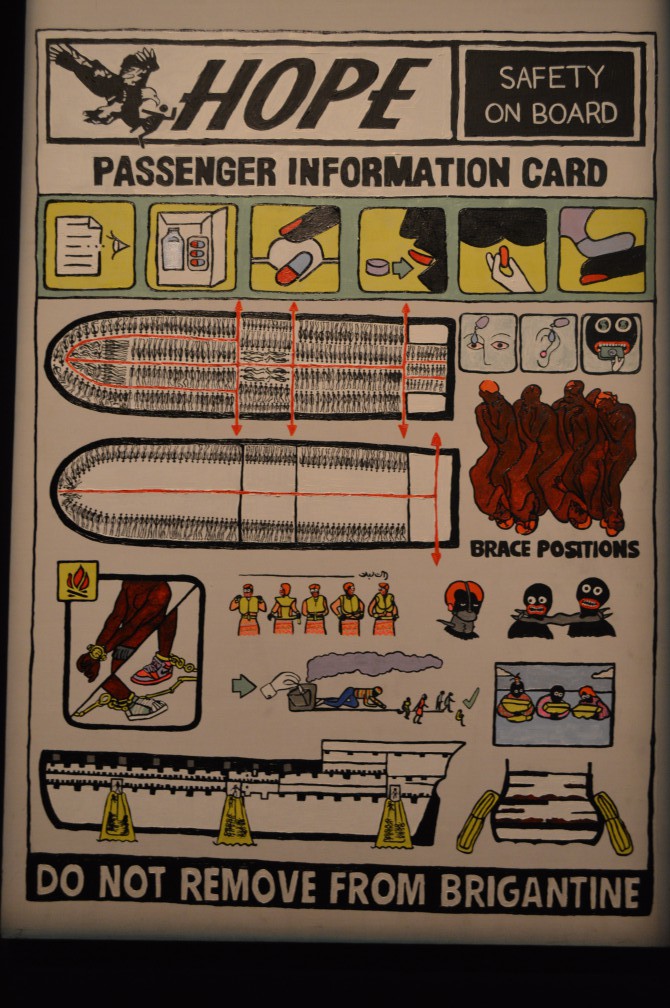

On a passenger information card, Makode Linde features emergency evacuation instructions for a ship transporting enslaved Africans. As is signature to his ‘Afromantics’ series, all of the typical figures (read: white) of a passenger information card are replaced with those in blackface. In a photograph from her ‘Back to Nature’ series, Annika von Hausswolff subverts seventeenth century portraiture of naked white women. Instead of soft fabrics or upholstery, the naked woman of von Hausswolff’s photo has been laid face down within a marshy nordic landscape. As described in its introduction, artists of the Baroque exhibit raise “questions about globalisation and the world order, the gaze and the physical body, death and impermanence, the creation of identity and roles, the spiritual, or our relationship with nature”.

The exhibit commands at least an hour but an entire day can be spent at Kulturhuset. On six levels, the centre is host to plays, films, visual art galleries, and a library. From my U.S. American viewpoint, the building is unique as an indoor space for public use. Seating areas are available without the pressure to buy tea from the cafe or a ticket to an exhibit (though visitors may have to navigate a bit to find a free toilet).

Tensta Konsthall

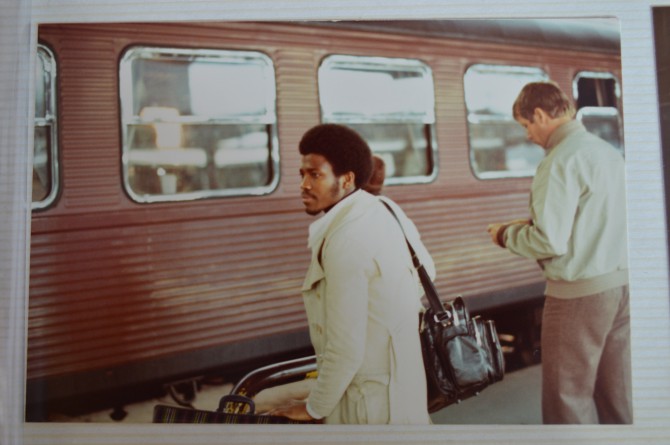

In the 1970s, the demographics of Sweden’s immigrant population shifted. Previously dominated by labour migrants from Mediterranean and Nordic nations, Sweden began to see an increasing number of asylees from the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Many of these immigrants settled in suburbs like Tensta and neighboring Rinkeby and Husby – all of which had been developed under Sweden’s Million Homes Program.

Although Sweden is often touted for its socially progressive policies, it has not been immune to Europe’s mainstreaming of political Islamophobia and racialised notions of anti-immigration. In the past four years, residents of these Swedish suburbs have collectively rebelled on at least two occasions. Civil unrest, lasting more than a week in May 2013, began after police killed an elderly resident of Husby.

Prior to my visit to Tensta Konsthall, it was explained to me that the art gallery had struggled to find its identity. By the time of my visit, the gallery seemed to be finding its balance, operating as a conversation between what is traditionally seen as the art world and Tensta as a community.

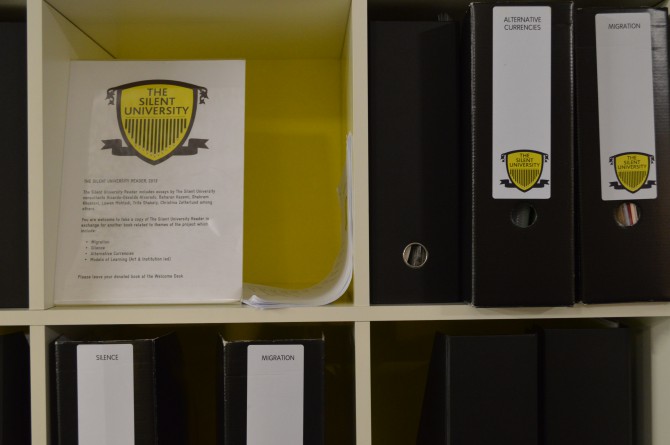

The gallery, which occupies the lower level of Tensta Centrum shopping centre, is the Swedish home of the Silent University. A two-city project, the university ‘recruits asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants with a professional background in their countries of origin’ to lead lectures or courses. At the Silent University, “careers that have been muted are included and reassigned”. In the university’s library are publications on silence, migration, and alternative currencies – all of which are available for exchange.

Tensta Konsthall is also home to temporary exhibits. Amongst the Summer exhibitions was ‘META and regina: Two (Magazine) Sisters in Crime’. The two international publications were founded by women in the 1990s. Independently, the publications are rooted at an intersection of art and feminism. As part of the exhibition guide, a conversation with the founding publishers and Tensta Konsthall staff was published. When asked of her experience of feminism in the ‘90s, Ute Meta Bauer (founder of META) recalled a collaboration with two women artists. The trio had initiated ‘The Information Service’ as an archive of female artists. Applicable to much of the work I saw at Tensta Konsthall, Bauer explained, “counter-archives are key to understanding and questioning histories”.

The People: Of Being Seen and Unseen

I stayed at a hostel on my first night in Stockholm. It was one of the few hostels that had female-only dorms. On their website, they made an appeal to solo female travellers: Stockholm is one of the safest cities and has some of the best looking men. I wondered what this meant for me, as a black woman.

Whenever I tell someone that I live in Chicago, my safety will invariably come up. I brush it off, “violence moves in networks” but the vulnerability that comes with leaving home throws all nonchalance aside. The random ways in which violence can move becomes real. In Stockholm, news of afrophobia and of attacks and protests from neo-Nazis unnerved me.

In the end, I never felt unsafe. It came down to the discomfort of being acknowledged or ignored. In walking the city, the feeling of being unseen dominated its inverse. Still, two encounters remain with me:

While waiting on the platform: Centralstation to Tensta

I eyed my phone, checking the directions to Tensta, hoping that I didn’t look like a nervous tourist. A woman wearing an ankle-length skirt approached me. She shook her paper cup and the coins at the bottom jangled. I waved her away, annoyed that she was drawing attention to me. She reached for my hand and I shook my head. No matter how often others assured me that Swedes love Americans, I refused to speak too loudly in public. The woman walked away and I went back to my phone. When I looked up again, there was a man walking along the edge of the platform. He had graying black hair that reached his waist and extraordinarily thick eyebrows. He was costumed, wearing too many layers for the weather. I made a snide remark to myself about The Lord of the Rings. His oddities held my gaze a moment too long. Just as I was turning away, he looked at me and as if he knew of my attempts to obscure myself, he greeted me, ‘helloooo Africa!’ and chuckled as he walked away.

And on my way back: Tensta to Centralstation

The two girls were standing at the top of a wide wooden staircase – something like fifteen steps between Tensta Konsthall and the metro station. As I stepped upward, they looked at me. The one who wore a white headscarf crowned by a ring of pink flowers eyed me. When I had arrived a couple of hours earlier, I experienced an immediate dissonance. The neighbourhood was predominantly Horn of African. I walked about, feeling as invisible as I do in predominantly white neighbourhoods but intensely aware of being West African. My invisibility there felt tenuous. Then I encountered the crowned girl. She was now sitting at the top of the steps. With the sun at my back, she squinted towards me. She twirled something between her fingers, her elbows at her knees, her eyes were still fixed on me. Her companion tried to enact the same boldness. They were no more than eight years old. I am still arrested: in her gaze and posture, the crowned girl was more than curious, she displayed an ownership of her space so much so that I am uncomfortable ascribing anything more to her.

There were other public encounters, none of which have registered as much as these two. I spent five nights in Stockholm. I had conversations with Swedes about race, cinema, and literature. I delighted in seeing black people perform the most mundane: walking with a lover, waiting for a bus, buying art supplies. I delighted in participating in the mundane: eating roasted potatoes or meatballs with jam, walking without aim, selecting desserts for fika. No doubt that my enamour with Stockholm’s everydayness is in part because it widened the narrative of what black life could be like in Sweden. So where the mys that accompany Swedish winters entices, I’d add the easiness of Stockholm summers.