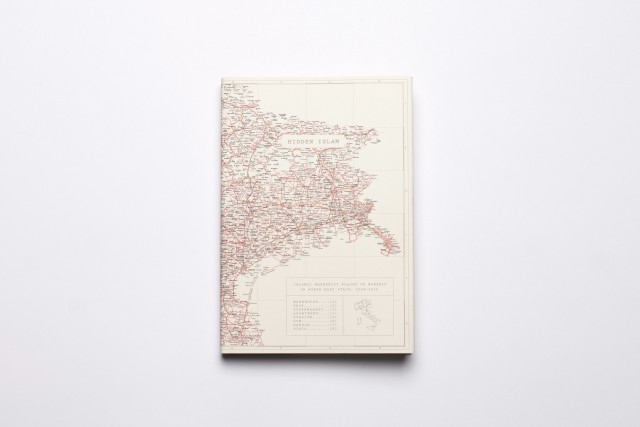

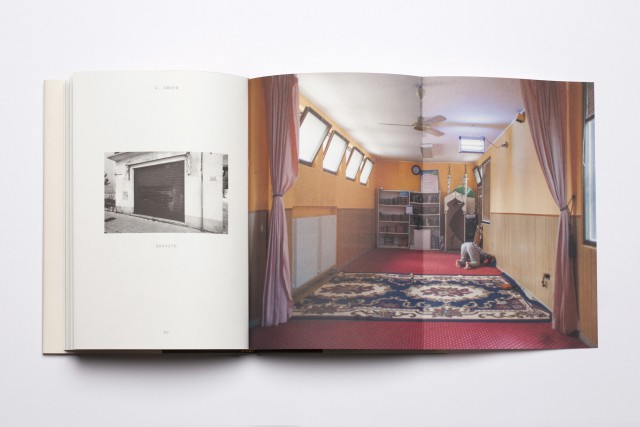

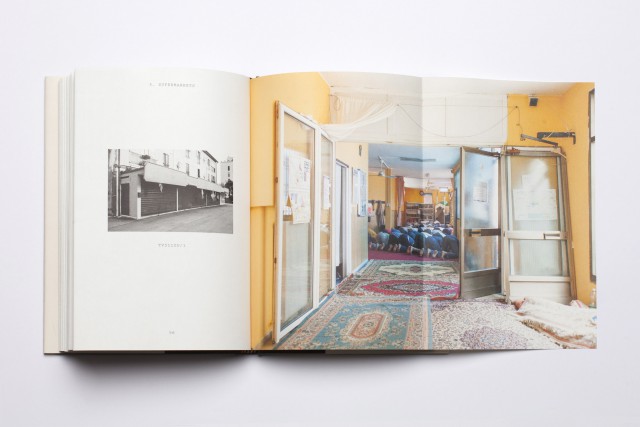

Mapping Mosques: Italy’s ‘Hidden Islam’ With Photographer Nicolo Degiorgis

By Tommy Evans

Afropean’s Tommy Evans recently met up with Italian photographer Nicolo Degiorgis to discuss his work ‘Hidden Islam’, winner of the Prix Du Livre D’auteur 2014 at Les Recontres d’Arles. The conversation was situated amidst ongoing Italian tensions concerning multiculturalism and immigration, from the abuse meted out to public figures like Cecile Kyenge and Mario Balotelli, to the rise of the far right. In this context, Nicolo has inventively captured the everyday struggle of Muslim migrants from North Africa to Italy in attempting to carve out a safe space for the expression of their faith.

Tommy Evans: Let’s begin with a brief outline of the current milieu.

Nicolo Degiorgis: The first Muslims arrived in the 1970s but those were students with no economic interests or a background of migration; they just came to Italy to study and stayed there. The rise in immigration over the past 20 years has changed the whole context. Nowadays, many Muslim migrants come from Albania, the Balkans, Morocco, North Africa and countries in Asia. That’s changed the whole situation; the Italian population wasn’t actually chateau gonflable prepared for such an event.

TE: There wasn’t a history of multiculturalism.

ND: No, there was not. So now, some parts of Italy are struggling, others less so but collectively Italians are facing immigration and finding ways to deal with it. The reason for doing this book was my interest in immigration generally, not Islam in particular. I’ve always been fascinated by traveling and other cultures so having the possibility to find other cultures in my own country was the driving force to do the book. ‘Hidden Islam’ depicts a very specific situation that can be seen as critical – and it is – because it concerns freedom of religion, a basic human right included in the Italian constitution. Nevertheless, it’s also very hard to define that line where you can say that rights are restricted or immigration happened so quickly that we didn’t have time to adjust – it’s a combination of the two things. Plus, migration varies throughout Italy and the economic situation is very different from the south to the north so that changes the context. My project depicts the north east of Italy; I was living in Treviso when I started the project and at that time, we had a populist extreme right wing party in government –

TE: Lega Nord?

ND: Lega Nord, yeah, and they had many issues with the Muslim community. I started there because I was working in a multicultural environment at Fabrica, which is Benetton’s communications research centre, and you have a lot of young people coming from all over the world from South America to Japan; and you could feel xenophobia and racism when you were in certain shops there. I was asked to research Islam because I worked on Islam in China – the Uyghur community in the northeast – for my university thesis. When I went back to Italy I wanted to work on a long-term project. Fabrica had this idea of Islam in Europe, assigning different photographers to projects in different countries. I started researching and I’ve been working on the project off and on for six years.

TE: How did you make contact with the project participants?

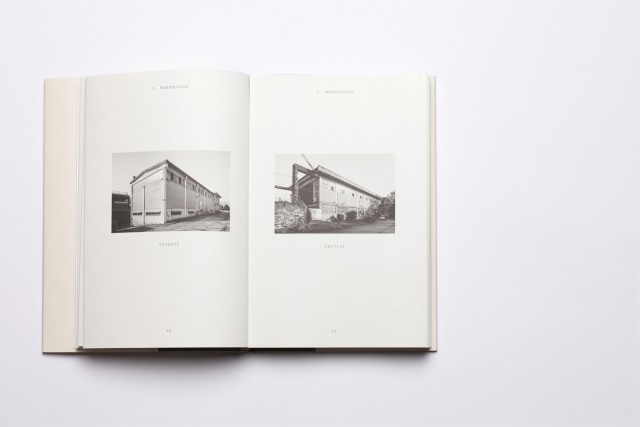

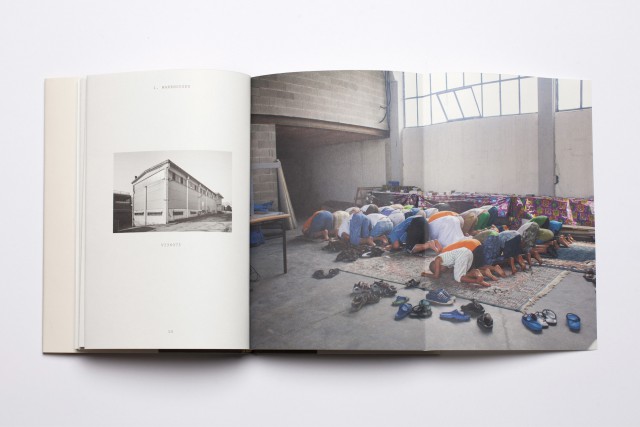

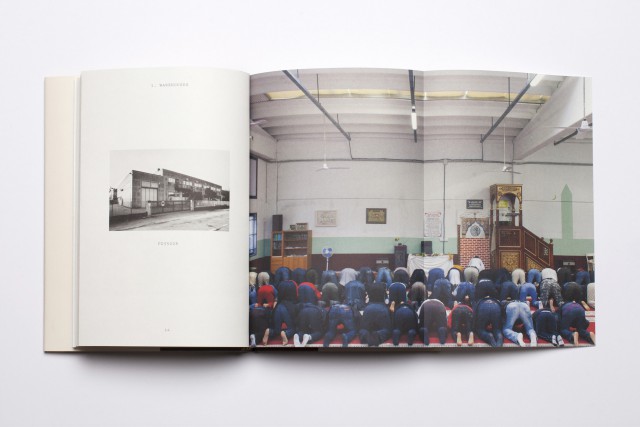

ND: What I did was approach the community that was the most visible – the community in Venice – on account of their website. I approached the head of the community and explained the project at that time, which was a very generic view of Islam. He took me to the first makeshift place of worship that was a warehouse. That fascinated me because you had this big warehouse, but when you entered inside, it was a musalla [a general prayer space, not to be confused with a mosque, an officially sanctified building for worship]. That left a visual impact: another world inside an industrial space. The north east of Italy is very famous for its economy so having migrants come from their home countries to produce wealth inside these warehouses that at the same time are places of worship – that initiated the project. From that community, I started researching Islam in Treviso (where I lived), and they had a hard relationship with Lega Nord. The community couldn’t pray in their warehouse so they had to pray in front of it even though they owned the building! This is where the project took an interest in a human rights point of view. After the first year, I understood I needed to map the places as there was no record of them and by the final year of the project, I managed to categorise the mosques architecturally since I had already completed the interior shots.

TE: It’s a very kinesthetic experience reading ‘Hidden Islam’. How did that come about?

ND: It came in the last year. I was making mock ups of the book, working, working, and seeking a publisher but nobody was prepared to take my project to the level I wanted. No one really believed a project about north east Italy could actually be done in English because I always had this idea of doing it in English.

TE: Why was that?

ND: Well, it’s because I usually work in English. I come from the north of Italy so I grew up bilingual, speaking Italian and German. If I did the book in Italian, it would have been an issue for me because it’s not German so I usually work in a third language. Also, English is universally understood and more common in the photo book scene. The project concerns Italy but it’s a situation that’s similar in many other countries, each one in a different way, but the truth at the core is always the same.

TE: What astonished me when researching your book was that there are only eight mosques for I.35 million Muslims in the whole of Italy!

ND: It’s not even eight. There are eight buildings that are seen architecturally as mosques but from a legal point of view, there is just the mosque in Rome.

TE: One?

ND: One. The Italian state establishes relationships with different religions but they don’t have that same relationship with Islam. The Italian government makes excuses saying the Islamic community is very diverse so they don’t find anyone to establish a dialogue with. At the same time, the Muslim community says that’s not true, we have our issues but we would be happy to find any kind of agreement. What happens in this game is people trying to practice their religion find some of their rights denied. You have some situations mechanical bull for sale where everything works smoothly, people have a place to worship, but in other cases, the police wait in front of the musalla at every prayer session without reason. It’s a strange situation. The practitioners of the religion suffer because of the bureaucratic and political situation that surrounds them.

TE: Finally, have you had a chance to share your work with Muslim communities in Italy?

ND: I presented the book three weeks ago to the head of the major association that includes all the Muslim communities and he was very interested, so now I’m going to help them expand the mapping –

TE: The whole country!?

ND: Yeah, because at the moment I’m probably the person who’s visited the most places of worship in Italy – more than any Muslim. It’s amazing because they hadn’t seen all these places, you know, it’s a new thing for them too.