Blue Story: Wrong Point of Vue

Written by Oliver Taylor

In the city of Birmingham, England, 13 and 14-year-old teenagers brawled inside Vue cinema while families queued to watch Frozen 2. Subsequently, showings of Blue Story were pulled by over 100 cinemas after Vue and Showcase Cinema banned the film, saying there had been several ‘significant incidents’ at screenings.

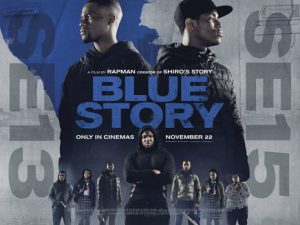

The film is about the futility of gang violence. It was made by Black British Rapper Rapman, known as Andrew Onwubolu, from Deptford, London with backing from the BBC and Paramount Pictures. Andrew’s parents are from Nigeria.

Latest sales figures since the film’s release from the Guardian show that by early December, despite or perhaps because of the ban, the film has earnt over 2.9million at the box office. So, following its reinstatement, it’s clear that from an economic point of view the cinemas did not make an intelligent decision, let alone a moral one.

During the ban and the subsequent furore, I went to the Peckhamplex cinema in Peckham to watch the movie, which accurately is where the movie is shot and set. After the film, there was rapturous cheer and applause from the cinemagoers. To say it’s influencing kids to go out and stab up some youts is inaccurate. The fact is, when the unrest started at the Vue cinema in Birmingham, the film had not begun at that point.

This is a film you will learn something from, and something right, not wrong. You will learn hard lessons. Blue story is a film I took back home with me. Back to the street where my family live. Back to the house with the curtains, I cautiously peer out of to see ‘likkle’ men run around with swords bigger than them.

There is a scene where Marco’s mother rushes into the hospital after her son is stabbed in the back. His mother, exasperated, cries, “that’s my son there, I’m his mother, and no one ain’t tell me nothing!” Leaves me wondering who’s really responsible here, and imagining the mum crying, ‘not me and not my son.’

This is just another day in the death of Britain (in the spirit of Gary Younge’s book of a similar title). Well summed up by the Manchester Evening News headline in May, ‘Another young lad dead and another mum’s life ruined‘. At the time, there had been a stabbing every 1.45 days in England and Wales.

The film is brutal and real. It felt legit seeing two boroughs of London: Lewisham and Peckham featured prominently in the movie, as both areas are where some of the gangs that are currently beefing are from.

How is it promoting violence if this is what is happening? This is their experience, so if you do not want to portray the abuse, do not expose them to the violence.

And why ban it? What was the rationale? Some petty, immature isolated incidences of young people carrying machetes into a cinema, which was blown out of proportion. The mass brawl at Vue cinema was a mass brawl, not some reaction to a screening of the film that hadn’t actually started at the point of the unrest.

Imagine being stereotyped as a bad boy and later pigeonholed as a young thug? Even though he start-offs like any other boy – with a family that shows him positive regard – society’s disregard wins. He sells some Lucazades in the playground to make some money because he’s poor and wants nice things that his parents cannot afford. Consequently, he gets suspended because his school does not see and guide his entrepreneurialism; instead, they see it as a gateway to theft and drug dealing. All the while, he internalises these negative narratives and continues to perform to toxic masculine expectations. Eventually, he ends up in a Pupil Referral Unit that’s full of other young people that have other problems. And so they just put them together and prepare them for prison – well known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

If a life of crime is all young males can see, Rapman and others like him are doing more than the current government for young people. A government which over the years has cut youth services, police, social care and mental health services. He’s giving young people an alternative, platforming them and giving them opportunities when institutions say they have run out of chances and we’re locking ’em up.

Blue Story is essential because it tells a story that is not shown. There’s no way it is inflammatory. The story is real; the story is happening. It doesn’t encourage people to go out there and commit violence; violence exists out there for social reasons, such as social exclusion, a lack of community cohesion and barriers to social mobility. I recommend it if you haven’t seen it.

Twitter: @otaylortweets

I’m looking forward to seeing Blue Story. My review of a French film called Les Miserables, which deals with police violence in a banlieu (housing estate) on the edge of Paris should appear shortly. Les Miserables will be released in UK cinemas in May 2020. Look on the positive side, if the cinemas hadn’t pulled Blue Story, would it have received the same publicity?