Film Review: Les Miserables

Audacious, powerful debut blends Afro symbolism with classic film language, provoking challenging questions about human social organisation.

Written by Tom Pointon

*Warning: The penultimate paragraph of this review contains a spoiler.

A profoundly moving, hard hitting moral drama elevated beyond being another ‘banlieu’ film through the masterful use of cinematic language and heartfelt performances from a largely nonprofessional cast. France’s ongoing tensions around identity, race and belonging expand, confronting the audience head on with dilemmas about the sheer difficulty of the human condition.

Emerging in France in the context of prolonged social unrest, Les Miserables inevitably draws comparison to 1995’s La Haine, described by one commentator as its ‘mirror’. La Haine followed three young men of Maghreban descent stuck in Paris city centre one night, having missed the last train home due to having been stopped by the police. By way of reflection, Les Miserables follows three policemen patrolling Le Bosquet housing project in Montefermeuil, on the edge of Paris, over two fateful days.

Twenty-five years on and nothing has changed in France. The liberal assumption of progress is shown as hollow and empty in a country divided between a metropolitan elite and those excluded, literally pushed away to the margins of the city. Left with little to nothing in the way of infrastructure or meaningful opportunities. Regularly told they’re ‘not enough French’ by dint of their religion or culture and subjected to racism.

Having lived in Marseille since 2014, not a year has passed without major unrest, recently in the form of the ‘gilets jaunes’ – an amorphous, spontaneous, leaderless movement occupying major city centres on Saturday afternoons and frequently turning violent. I’ve witnessed for myself scenes shown in the film – teenagers frisked by the police because they’re waiting at a bus stop, or made to sit on the pavement, handcuffed. The anger in France, as indeed many countries, is palpable. At the time of writing, proposed pension reforms have led to weeks of strikes and demonstrations.

Les Miserables has been criticised for avoiding a position. This misses the point of the film. The same rage expressed by the gilets jaunes through violent, destructive acts, finds its counterpart here. The arson and wonton destruction reminiscent of the inchoate rage of a small child throwing and breaking its toys, thwarted when it realises it has absolutely no power. The citizen disempowered by an oppressive, indifferent and indeed hostile state being a trope of our times… the film doesn’t offer answers, instead it pushes back, confronting the audience with the imperative to start working out what the questions are which need asking.

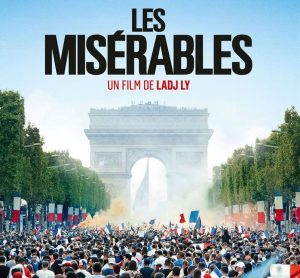

The film opens with young black teenagers celebrating France’s 2018 World Cup victory in Paris, amongst them one of the protagonists, Issa. This introduction concludes with a shot of the Arc de Triomphe, over which is superimposed the title Les Miserables (the teenagers we’ve just seen being spiritual descendants of Victor Hugo’s novel). Assuming the same title, locating his film in Montfermeil where Hugo’s classic novel was also set, Ladj boldly inserts himself into a canon of French auteurs and ensures the posterity of this audacious debut.

According to Benedict Anderson in his influential book Imagined Communities, the ‘nation’ is an ‘imagined community’ and it’s through cultural and sporting events such as the World Cup that people literally ‘imagine’ the nation – a large, amorphous community of people who otherwise wouldn’t know one another – into being. At a time of anxieties and discourses around national identity and who can be considered properly French, the irony of France’s 2018 World Cup victory was that most of the French players, by virtue of their background or parentage, were eligible to play in the Africa Cup of Nations. Indeed, some commentators argued it was Africa that won the World Cup for France. Les Miserables shows this ‘imagined community’ as a facsimile. Rather than community, there is an uneasy stasis of competing, antagonistic groups.

Following the World Cup, three policemen: Chris (Alexis Manenti), Gwada (Djebril Zonga) and newcomer to the team Stephane (Damien Bonnard in his first major lead role) are looking for a thief who’s stolen a lion cub from a travelling circus – they have a limited amount of time – if the cub isn’t returned, war will erupt between the various patriarchal groups who live uneasily alongside one another in the cité.

We’re introduced early on to Issa, the guilty party, at the commissariat. Evidently stealing is a habit. An infuriated shopkeeper cuffs him around the head and has to be restrained. Stealing has a meaning here, as will be explained shortly.

When not subtly bullying newcomer Stephane (‘he needs a nickname’), Chris abuses three girls waiting at a bus stop. While Gwada looks on, Stephane attempts to intervene and defuse an escalating situation. The state is the ultimate patriarchal authority, its power here manifested by the police. Social organisation is contingent upon order and equilibrium which is maintained through force, violence or threats of the same. There’s one scene when Chris, attempting to negotiate with the community leaders, becomes increasingly aggressive, shouting out ‘I am the law!’ Stephane has to intervene and takes Salah (Almany Kanoute), a community leader who acts as an intermediary, outside. We see the two men, from inside the shop, through a window, but we can’t hear what they’re saying. Clearly, the need to listen is paramount.

The liberal enlightenment project assumes the inevitability of ‘progress’ – it’s only a matter of time before everyone, everywhere in the world, adopts European (French) systems of democracy, liberal capitalism and so on. Human beings are rational and reasonable, living peacefully through democracy, state institutions and the rule of law. Far from operating through reason, however, human beings are driven by unconscious drives, frequently behaving in ways contrary to their own interests. Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely, as evidenced by the casual cruelty of Chris.

The film has a novel stylistic approach, combining documentary style ‘camera a l’epaule’ (handheld camera following the actors at shoulder height) with altogether more spectacular use of drone shots soaring above the apartment buildings. This implies freedom, escape yet also something more sinister. Early on the viewer is implicated in the pubescent voyeurism of the boy Buzz (Al Hassan Ly, the director’s son) using his drone to spy on women – we see from his point of view, implicating us in his voyeurism which confronts us with how so often people in marginalised communities are used by politicians and the mainstream media as objects to be exploited for entertainment or political purposes. What’s our purpose in watching this? How many times have we watched prurient documentaries about ‘tough gangs’ or ‘problem estates?’

Another effect of the drone shots is to situate the characters in their environment and emphasise the extent to which they are formed and shaped by their physical surroundings and circumstances. Everything is interwoven, interconnected and interacting in myriad ways. The police are under intense pressure, hence their behaviour, which has a negative effect upon the community they’re supposed to police.

While District 13 or La Haine are obvious comparisons, Les Miserables shares a number of aspects, including one crucial scene in particular, with Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959). Both films follow marginalised, excluded children. The same difficult age, twelve or thirteen, moving away from childhood into adolescence. Both films use real life locations and draw upon the real-life experiences of their cast. This is a kind of cinema allowing the flux and unpredictability of life to enter. In both films there’s a sense of the actors ‘being themselves’ through clearly improvised scenes and dialogue.

Located in an ‘ancestral Paris’ in the ninth arrondissement, the cramped apartment where the Doinel family live in The 400 Blows reveals the capital’s serious post war housing crisis. At this time Paris was ringed by bidonvilles, or shanty towns. Sixty years on not only are the shanty towns reappearing, this time populated by people who’ve fled wars, persecutions or simply economic hardship, but the cités such as Les Bosquet, built in the sixties / seventies to replace the bidonvilles, have in turn become a byword for social and economic ills.

Anne Gillain’s essay on The 400 Blows called ‘The Script of Delinquency’ draws on the writings of psychotherapists DW Winnicott and Melanie Klein, who worked extensively with disturbed and troubled children. Returning to Gillain’s work helps account for why and how Les Miserables is so much more than just another ‘banlieu’/ social realist film.

Issa’s mother in Les Miserables appears, like Mme Doinel, in The 400 Blows, indifferent towards her son. When the cops call at her flat, looking for him, she doesn’t know where he is. Instead, she shows Gwada a room full of female friends counting out money. Clearly she has other priorities, like Mme Doinel, who’s more interested in weekends away with her husband, who isn’t the boy’s father – without her son in tow.

Stealing is central in both films – Gillain draws on Winnicott’s interpretation of stealing as being ‘a gesture of hope’ on the part of the child to reclaim the care and love which hasn’t been forthcoming from their parent(s). Lead actor Issa Perica is perfectly cast as Issa – cub like with his delicate features, light complexion, beige combat pants and sporting a T shirt with a lion motif explicitly identifying him with the animal. This however is an animal destined for a life of imprisonment as a circus ‘entertainer’. By stealing the cub Issa at one and the same time reclaims the nurturing to which he’s entitled and by liberating the animal from the circus expresses his own yearning for potential beyond the confines of his current life. Growing up on estates like Le Bosquet, physically and socially excluded, the potentialities of young lives like Issa’s are unlikely to be realized.

The lion holds further connotations. In Rastafarian culture the creature is an embodiment of Emperor Haile Selassie, the sole leader to have expelled European invaders from an African nation (Italy from Ethiopia) and is seen by members of this religious movement as the one who will lead the lost tribe of Rastafarians back to their rightful homeland.

In ancient Egypt the lion was more ambiguous – it’s strength can become tyrannical. By stealing the lion cub, Issa symbolically attempts to stem the possibility of tyranny. Lions were often in pairs, expressing at once the dawn and also the dusk, the end and beginning. The lion consumes the day and might be read here, imprisoned as it is in a circus, as indicative of the dusk of Western industrial civilisation, when the promises of liberal humanism seem exhausted, the faith in progress extinguished.

It might be pushing the analysis too far to draw an analogy with the biblical story of Daniel in the Lion’s Den. In one scene the terrified boy is brought face to face with the lion cub’s parent. Beyond roaring, the animal can do nothing. The message of the bible story is that faced with falsehood one should stand firm in one’s beliefs.

Psychoanalytic theories account for delinquency as being one of the consequences of failures of parenting. If the parent isn’t able to give the child appropriate relationships and nurturing behaviours, the child’s personality will be malformed. He or she will be incapable of behaving in a socially acceptable manner with others, and delinquent behaviours such as stealing and violence are the result. Successful psychosocial development consists of moving from the maternal world out to the world of patriarchal authority. Both worlds in Les Miserables are found wanting – the mother is indifferent, the father incapable of leading his son by proper example. In place of calm authority supported by consensus, we have tyranny based upon strength: the circus men with their gym pumped bodies and ultimately the state, in the form of the police.

If women have little visibility in Les Miserables, I read this as a comment by Ly on the macho posturing of the patriarchal society he reflects. Men, by occluding women, don’t do a very good job of things. In place of listening, dialogue, discussion and working together towards a shared objective, we see them shouting and squaring off to one another. Women however, when they do appear, are strong figures. Teenage girls answer back when provoked by the cop Chris, an inadequate little bully of a man. An enraged mother intervenes against the cops’ abusive questioning of four small boys.

If the state has abandoned these kids, literally excluding them and their families to the peripheries, then adults, such as the owner of a fast food stall who turns the kids away when they ask him for food, are shown to be equally indifferent.

During a scene when the boys are invited to the mosque, the camera closes in on the Imam and his co-worshippers, wearing Islamic dress and beards. One boy yawns. Religion, with its imperatives of dress, conformity of appearance, closes down possibility. By contrast, when left to their own devices – playing basketball, making slides from discarded car doors or goofing around in a paddling pool with water pistols – possibility and spontaneity are expressed through camera work which opens out to long, expansive shots. Envisaged by the state as ordered, regimented public housing, the cité becomes instead a locus for the imagination – space around the blocks is reclaimed as somewhere to play. A similar binary operates in The 400 Blows with interior shots (carceral space) contrasted with exterior – the city as a place of exciting potentialities.

Carceral (prison) space manifests through cars. Patrolling the cité the three cops are confined to their car, unable to leave it for fear of attack. Ultimately, the custodians are metaphorical and soon to become literal prisoners themselves, in contrast to the kids, who occupy the space of the cité.

Little distinguishes the cops from criminals. At one stage, Chris negotiates a favour with the criminal owner of a sheesha lounge. Where’s the moral compass? The police here, as representatives of the state, behave in ways which are anything but reasonable and rational. Their lack of integrity and abuse of power shown by their casual cruelty towards the children they’re supposed to protect.

The self-appointed ‘Mayor’ of the cité (Steve Tientchu) operates some kind of scam with the market traders. He’s seen by the boys as another abusive figure, eventually being set upon and beaten by a mob. This reflects the situation across Europe and indeed much of the rest of the world. A political class, indifferent to those they ‘represent’, using political office to further their own interests.

Finally, staircases and trash feature prominently in both Les Miserables and The 400 Blows, although as different signifiers. At one point, Stephane is at the foot of the stairs of an apartment block, in the foyer, calling for reinforcements, unable to give his position. There’s no address on the building; this is nowhere and everywhere. Les Bosquets stands for every marginalised, excluded community, indeed estates like this are to be found on the fringes of every French town and city, populated in the main by those considered ‘not enough French.’

At the films climax the stairways become a trap. The apartment block becomes a space controlled by the kids, who’ve been filling shopping trolleys with discarded objects to then use as weapons against the police. Who is really imprisoned here? For me, it is those who lack the imagination to free themselves by thinking about other possibilities of how to live. Those who need to oppress others to bolster their precarious sense of self. Given human nature, is human social organisation ever possible without manifesting oppression, tyranny or abuse?

(*SPOILER ALERT)

The 400 Blows concludes with one of the most famous of all film endings. Antoine, running, turns, faces the camera, staring directly at the viewer, the action freezes. The choices facing Antoine are encompassed in that one frozen, existential moment. By contrast, at the end of Les Miserables, choices have closed down. Having trapped the police in a stairwell, Issa holds a petrol bomb aloft. Stephane aims his gun at the boy. What choices do either of them now have? Instead of an existential moment, the choices made by the characters have brought each to a deadly inertia. Like Antoine, Issa stares back at the viewer. The audience is forced to consider whether any of us, ever, really has a choice or autonomy over our decisions, contingent as they are upon circumstance and influenced by lived experience.

Like Truffaut did sixty years before him, Ladj Ly expresses a universality through Les Miserables. The Antoine Doinel of ‘50s/’60s Paris has his counterpart today in the form of Issa. Dysfunctional institutions and indifferent adults continue to prevent plenty of lost boys (and girls) reaching their potential. An ‘auteur’, once again speaking about what he knows, boldly tells his story from a banlieu every bit as French as Truffaut’s ninth arrondissement Paris. Sweeping Cannes and nominated for the academy awards, this stunning first feature is the perfect riposte to those who’d consider a filmmaker of Malian parentage and Muslim background ‘not enough French’. Hopefully it marks the beginning of a more constructive acknowledgement in France of the considerable fault lines cracking the Republique’s veneer of liberté, egalité and fraternité. Maybe even another ‘French new wave’ of new voices and talents.

Postscript: At the time of writing, more parallels with Francois Truffaut emerge. Truffaut acknowledged film critic André Bazin as having been a surrogate parent who saved him from a life of crime and delinquency by introducing him to film, first as an exhibitor-critic and then as director. The casting of Jean Pierre Leaud as Antoine was deliberate, a boy who’d also had similar difficult life experiences to Truffaut. A recent scandal in France sees Ladj Ly suing a journalist for defamation of character and racism. A story and judgement from 2011 were uncovered, during which Ladj Ly was apparently present when relatives of his carried out some criminal activity involving an abduction and he was eventually himself convicted. He’s always maintained his innocence of any wrongdoing, arguing he was present at the scene of the crime because he wanted to mediate and prevent violence. Given the strict privacy laws in France as well as a pending defamation trial, it’s difficult to get much in the way of information about this story. There are however striking parallels with Francois Truffaut, a director who experienced trouble when younger and who was redeemed through film.

Les Miserables was released in France in November 2019; the UK release is set for 24th April 2020.