In Preliminal Space: Notes Before Leaving Home

Written by Oliver Taylor

Nina Camara has a fascinating series featured on Afropean, called Liminal Space. At the centre of Nina’s interviews with other Afropeans is her interest in highlighting “the experience of people who have decided to leave an environment which did not reflect their story for a liminal space, ‘between the known and the unknown’, in order to put their past behind them and create a new beginning somewhere else.” Nina opens her series with the words “though the face of Europe may be constantly changing, on a social level that change is often not fast enough.” I couldn’t agree more. We might be a diverse bloc, yet we’re far from inclusive, especially with recent political events in Britain. My story is no different, and Nina inspired me to share it.

I haven’t left home… yet, so I’m in the Preliminal Space, and I’ve decided to go – in search of belonging. My story could offer something to Afropeans, like me, still taking up Pre-Liminal Spaces. For those of you who want out. If you are planning to leave, consider leaving on a high note as I hope to. We’re lineage holders, let’s have an impact. Your end could look and mean different things to mine, disrupting white-majority spaces as you leave, and telling people why you’re going, or not mentioning it at all.

Growing up, like Nina and the others, in white-majority spaces, in my case, the city of Lincoln, England, means I understand the invisible challenges we face where there aren’t many of us. More so as I’m still living here; it isn’t a distant memory that I’m thankful is no longer a reality. I’m still, as Malcolm X put it, ‘catching hell’, longing for a more immersive multicultural safe space, where I don’t suffer integration fatigue daily.

Life at Home

Describe the place where you grew up. What was it like in terms of cultural and ethnic make-up?

I was born in the City of Lincoln, of Lincolnshire, a rural county which is the second-largest county in England. I still live here. The country’s non-white population was no more than 2.5% in 2011, and the city’s 4.4%. I was the only person of colour in my primary school. I knew of one other mixed-race boy in my village. Our family didn’t know of any other people of colour locally. The city wasn’t much different, apart from within my own family, I knew very few black people. If we did see black people in the community, the chances were parents knew them from passing in the street. My mum and dad would joke about those days that you could count them all on your two hands.

How did you feel growing up in this community?

It’s strange, because I think I have always felt the way I felt until recently. Just under the surface, I was feeling out of place, feeling bizarre, and feeling guilty as a result of a general underlying hostility from my community.

Yet not being able to shake the experience of being seen as suspicious or deviant. I’ve always been self-aware and highly sensitive, but I’ve not had the language to interpret my surroundings, so I guess I thought what I felt was normal, just general anxiety that other people felt.

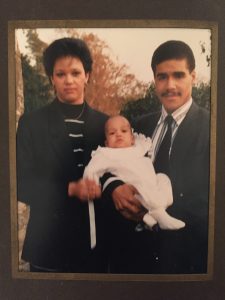

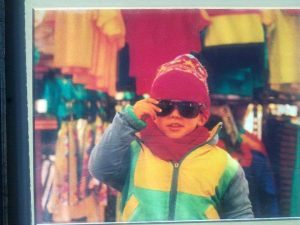

I was called dirty, by a white pupil at school, and I remember the hostility of two brothers towards me. At the time, I didn’t know it was colour. I got lauded for my dance and athletic skills. Winning running competitions and praise at school discos – not knowing I was being pigeonholed as Black with a superior physicality – both positive stereotypes, but rooted in ‘race-based thinking’. I guess my parents protected me, though they didn’t discuss race with me, they spoke to the headmaster at the school to deal with racism head-on. His wife was black/Asian biracial, the same skin colour as us according to my mum, so he empathised. The older white men around me always seemed overly paternalistic. My parents felt it best not to focus too much on the colour of our skin in our everyday lives. They had little knowledge of their own African ancestral roots back then. My mum has Kenyan heritage (Maasai and Kikuyu), as for my dad we didn’t have a clue about his African heritage (now we know, through an African Ancestry DNA Test that it’s Angolan (Mbundu (Bantu)). My mum described herself as white in term of upbringing and socialisation, while declaring herself as ‘half African’, which was cool (today she feels an affinity for the term biracial). My dad loved Michael Jackson songs, and I remember him vividly yelling in public that he was black.

How did people react when they first met you?

There were usually comments about my hair, such as how many older white women wished that their hair would curl like mine (perms were big back then). School children in my class would debate my race, saying “he’s not black,” “yeah but he’s not white either.” People were more likely to question where I was really from and assume that I’m not from my town, that I’m not a local because I’m not white.

Looking back, even though to a certain extent, I couldn’t see the wood for the trees, it’s apparent that I’ve put up with racist treatment, and it’s embarrassing. It’s hard to believe what I’ve tolerated, even from people I thought of as ‘friends’.

Nina Camara offered a perceptive interpretation of growing up as a minority: “one of the most toxic features of the spaces with no diversity is moral blindness. How they also teach you to be blind, so you excuse inappropriate remarks and even overtly racist behaviour. I feel embarrassed looking back at the stuff I used to accept.”

Were there any challenging situations? How did you approach them?

Yeah, at school, it was pupils making assumptions, due to their limited exposure to PoC. Trying to box me in, with questions like “He’s not white’, ‘He’s not ‘black’. I didn’t know where I fit either. It was humiliating and honestly degrading at times. I remember being asked if I could be called the N-word. People often asked me what my roots were, and I knew very little of the black side of my family’s history. It’s uncharted territory with gaps and blanks, due to the circumstances of both my parents’ birth. Both are bi-racial black, each with a black father, yet have no contact with them, and never had really.

So, my reaction was often confusion, I’d let behaviours slide. I remember being called a “black &£$%” for simply walking into someone by accident. I just tolerated it.

How and why do you want to leave?

Despite my environment, I am not (that) bitter – on the contrary, I’m better. I heard Angela Davis speak of growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, and how it taught her a lot about racism and white supremacist patriarchal society.

I think there’s a silver lining to Lincoln’s clouds. It’s encouraged me to trace my African and Irish roots, seek out supportive communities of colour, and understand how through Empire I live in Europe with my cultural heritage. As co-founder of Afropean.com Johny Pitts points out, “what joins Afropeans together is a history of colonialism.”

A central push factor is feeling displaced due to Empire. Although this has affected my identity to its very core, I literally wouldn’t be here, for better or for worse, if it wasn’t for the colonisation of the African continent. As Afua Hirsch says, ‘I owe it my life’.

All this consciousness raising has allowed me to disrupt spaces and call out racism, sexism and other forms of oppression. I am taking a stand against sexual harassment at work, race-based thinking of friends and family, and unconscious bias in my white-majority church. Talking about race has had an impact, though I don’t think a huge one. I want to leave on a high note or at least a constructive note.

Where would you like to move?

London. I often travel to London, to escape, to explore and to feel what it’s like to be part of Black Europe, un-isolated amongst other Afropeans. It’s there that I feel a greater sense of belonging and solidarity. Living in the Preliminal Space is culturally isolating, it’s painful. I encourage anyone to bear through it, as a supportive friend said who moved to Atlanta (known as the chocolate city), it’s the weaker part of you dying. Gain strength, put yourself first and seek out immersive spaces.

Twitter: @otaylortweets