Behind Somalia’s Architectural Renaissance: I

Written by Adama Juldeh Munu

Rebuilding after conflict is never simple. Countries such as Rwanda, Bosnia and Sierra Leone can attest to this. In this series, Adama speaks to Somali-Europeans that are combining culture with sustainable development to reconstruct Somalia’s urban landscapes.

It’s October 14, 2017. More than 500 people were killed and 400 injured, when two trucks filled with several hundred kilograms of military and homemade explosives were detonated at one of the busiest intersections in Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu. It’s described as the deadliest terror attack in Somalia’s history. The terrorist group Al-Shabaab claimed responsibility for this, and a series of other sporadic tragedies that have occurred ever since.

Contrary to popular belief, Somalia is not in a ‘state of war’. But like other post-conflict countries, peace and stability have a difficult and sketchy trajectory, following two decades of civil unrest, state collapse, warlordism and weak transitional governments. However, a group of young Somalians whose parents emigrated or sought asylum in Europe, are fomenting an architectural revival to celebrate Somalia’s culture.

Omar Degan is a Somali-Italian architect that is a part of this growing cohort of diasporic enthusiasts that want to contribute to rebuilding and commemorating the very best of their ancestral history. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture for Sustainability between the Polytechnic University of Torino in Italy and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and specializes in Emergency Architecture and Developing Countries with a focus on post-conflict reconstruction.

While returning to Somalia was an opportunity for him to reconnect with his heritage, the demands to construct projects were always going to be immense. As Degan explains: “the challenges [in Somalia] are similar to other post-conflict countries where war is the final result and there’s been destruction. The biggest challenge is to give a sense of belonging which means [one has] to recreate buildings, and attachments that people have to public spaces and buildings.”

These attachments are subjects of a book he’s released in July, ‘Mogadishu through the eyes of an architect’. It maps out the city’s most important buildings and monuments, whether that be a monument commemorating Ahmed Ibn Ibrahim Al-Ghazi, ‘The Conqueror’, who fought against the Abyssinian Empire. Or that of Somalia’s Dervish movement, Sayyid Mohamed Abdullah Hassan who was a patriotic anti-colonialist. He says they make up the “silent bearers of our history”.

I first became aware of his artistic pursuits back when I reported on the October 14 attack, and it was very clear to me at the time that he had a strong and impassioned desire to use the educational instruction he gained in Europe to give back to Somalia. One of the ways he wanted to do this was to design a monumental tribute to the October 14 victims, entitled ‘October 14’.

“This memorial wants to fix in the memory of the people and the urban space of Mogadishu the terrible memory of this terrorist attack, because I believe that despite the pain, it’s our duty to remember the victims,” Degan says. ‘October 14’ was not conceived as a simple monument but as a garden. The spatial dimensions would allow visitors to walk past over 500 rectangles embedded in the ground, each of which represents a victim of the attack. Then there are the rectangular embedments in the ground designed with the same breadth as a prayer rug, to function as a spiritual gathering space.

The other projects he’s been involved in include a community centre for young people and women in Baydhabo in the southwest of Somalia. And a library in Somalia’s Sool region, which has around 720,000 inhabitants who have little access to educational facilities.

I recently spoke to Degan about his latest venture, which he described as his “most iconic project and social experiment” to date. He has designed a restaurant called Salsabil in central Mogadishu which combines a modern contemporary look with the essence of Somali culture and heritage. The name Salsabil is taken from a verse in the Qur’an which refers to it as one of the water springs of Heaven:

“And there they will be given a cup whose mixture is of Zanjabil (ginger). A fountain there, called Salsabil.” (Quran 76:17-18)

Salsabil is made up of two floors: the ground floor is for a contemporary traditional cafe where Somali coffee is sold, and the upper floor is a restaurant. The interior of the restaurant is stunningly contemporary, with oatmeal white tables and walls, the latter laden with black and white photography detailing Somalia’s cultural and historical aesthetics. The modern lighting drapes from the ceiling resembling a ‘spring’, but it’s the drapes of traditional red and gold coloured material arranged across seating and some of the restaurant’s walls that give the restaurant a quintessentially Somalian essence and aurora.

“We tried deeply to put together a contemporary design but to bring back the cultural identity of Somalia by using local design and material and using local craftsmen,” Degan explains. “The experiment was in an area that was underdeveloped but giving it a high quality and interior design and space. The response of the people was great, which is proof of how design and architecture can bring back life in the neighbourhood.”

In recent years, there has been a flurry of new architectural projects across Africa, to match the great feats of the past, many of which still remain and are standing, such as Mali’s infamous Sankore University and Algeria’s Clay Palace. Senegal’s Black Museum of Civilisations opened in Dakar in 2018, 52 years after the country’s first president Leopold Sedar Senghor first proposed the idea at an arts festival in Dakar in 1966. The museum’s core objective is to celebrate and educate on the contributions of people of African descent on the continent and beyond.

And part of Africa’s architectural integrity has also been the artists who have masterminded some very impressive projects in Europe and the United States, including Burkinabe France Kéré who combines his training in Germany with African methods to incorporate solutions to high temperatures, lack of resources and seasonal weather. And British Ghanaian David Adjaye, the lead designer behind the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. He incorporated African marble and decorative ironwork found in Southern architecture that was often made by enslaved African Americans.

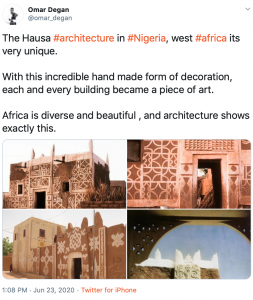

Degan’s projects take on a nationalist fervour, but he tells me that he views his work as part of the larger tapestry of change taking place across the continent through architecture. According to his Twitter biography, he is a self-professed pan-African, and often tweets photographs of different architectural wonders across Africa.

Naturally, African architecture is by no means homogenous, and as design researcher Mathias Agbo Jr argues, some countries like Mali, Sudan and Niger have been more successful than others in preserving and protecting their indigenous architecture. In my native home country of Sierra Leone, for example, the houses built by freed slaves of the Krio ethnic group are currently in disrepair.

“My hope is that through the cultural identity of Somalia and other African countries, we can bring back a strong sense of belonging. We become proud to be Somali and African,” Degan concludes. “We have to be proud of who we are, and where we come from. And I believe that architecture is the representation of this cultural identity. Architecture can be a symbol of a renaissance and a new modern era.”

Adama Juldeh Munu is a journalist and producer that is passionate to tell stories relating to the African diaspora.

You can catch up with her on twitter: @adamajmunu