For Glory and Country: Wladyslaw Jablonowski, Afro-Polish General in Revolutionary Europe

Written by Robert Fikes, Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

In contrast to the more widely celebrated accomplishments of three other African-descended military standouts in 18th century Europe — namely, Abram and Ivan Gannibal in Russia and Thomas-Alexandre Dumas in France — the perilous exploits of Poland’s deeply patriotic Wladyslaw Franciszek Jablonowski have for too long remained in the shadows.

Jablonowski’s socially awkward and rather embarrassing birth in Gdansk, Poland, on October 25, 1769 was preceded by his conception in Paris, France. His mother, British-born Princess Maria Franciszka Dealire, had had an adulterous affair with an unnamed liveried Black servant. Her husband, Konstanty A. Jablonowski, a Polish army officer who became Inspector of the Royal Mint in Krakow, seemed blithely unperturbed when her newborn was delivered with “features and skin color (that) were decidedly negroid.” Confronting his wife with clear evidence of her infidelity, Konstanty, also known to have been unfaithful to Maria, was hardly unhinged by her explanation that she had been miraculously impregnated by a wax effigy of a Negro holding a pipe outside a tobacconist shop. His voice dripping with sarcasm, he inquired: “That’s fine, my lady, but where is the pipe? I don’t see anything in the infant’s mouth.” The boy was nicknamed ‘Murzynek’ (translated as ‘Pickaninny’ but not meant as a racial slur at the time).

Perhaps because Konstanty desperately desired a male heir regardless of colour, and since anti-Black racism had not firmly taken root in Eastern Europe, he treated the boy as though he were his natural offspring, and with fatherly indulgence he started his ‘little Negro’ on a similar career path to military and government service. At age 14 young Jablonowski was sent to the elite Académie Militaire de Brienne, a branch of the Ecole Militaire de Paris (Paris Military School). During one school year he was a classmate of Napoleon Bonaparte, the future First Consul and Emperor of France, who treated him with utter contempt and verbally abused him on account of his brown skin. There was one occasion when he parried the Corsican’s insult, telling him: “Better to be a Negro with a white heart than a white man with a black heart.” He did, however, attract other loyal friends at the academy, most notably Louis Nicolas d’Avout, Duke of Auerstaedt and Prince of Eckmühl, who later became Maréchal d’Empire under Napoleon.

In 1786, upon finishing his studies at the academy, at age 17 Jablonowski was commissioned a lieutenant in the Royal Allemand Regiment. The regiment was comprised largely of German-speaking and foreign-born soldiers who were considered more reliable than native Frenchmen if ordered to break up a disturbance or subdue a rebellion. An extended stay at home in Poland resulted in the temporary loss of Jablnowski’s officer’s commission in the French army. With the explosion of the French Revolution in 1789 he cast his lot with those intent on overthrowing the Old Regime but the exact nature of any subversive activity he may have undertaken in France is unknown. In Paris he witnessed the downfall of the monarchy and survived the Reign of Terror.

Young, dashing, and ambitious, Jablonowski next surfaced in 1794 in Poland in the midst of the Kościuszko Uprising, a popular insurrection sparked by the invasion of Poland and Lithuania by the armies of Russia and Prussia, whose rulers sought to maintain their oppressive grip over the region. Jablonowski, one of the founders of the Central Assembly (later Lviv Assembly) that contested the partitions of Poland, lent his energy and intelligence to the cause of Polish unity and autonomy. He displayed bravery in the battles of Szczekociny and Maciejowice. When the fighting shifted north, he was put in command of the Kraków grenadier battalion and the Kraków militia. Elevated to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, he led them in the battles of Warsaw and Praga. In the closing days of fighting, 20,000 defenseless Poles were massacred. The uprising was crushed but Jablonowki’s reputation as a “good tactician and effective organizer” was established.

In the aftermath of defeat Jablonowski conspired with his Polish comrades to restore his country’s political integrity. Evading capture, he fled to Austrian-controlled Galicia where he and other refugees plotted, with the assistance of some French operatives, to retaliate militarily against Russia. Assuming the role of provocateur, in 1796 Jablonowski arrived in Constantinople (today Istanbul) on a secret mission to, in part, do whatever he could to instigate a raid into Russian and/or Austrian territory. Predictably, the mission to involve the Ottoman Empire in such a fanciful scheme came to naught. He then trekked to Bucharest to join with another band of Polish exiles who strategized to reunite their subjugated motherland, a dream they shared that proved wholly unrealistic.

According to historians Jan Pachonski and Reuel K. Wilson, with the formation of the French army’s Polish legions in 1797, Jablonowski resumed his military career. Tasked with leading a calvary brigade, in 1798 he fought “with great distinction” on the side of France against Austria, all the while still hoping France would one day intervene militarily on behalf of Poland. In the Franco-Neapolitan War he took charge of several hundred Italian troops from the Roman Republic in the Battle of Santa Maria di Falari, and directed a French rifle brigade in the battles of Magnano and Cassano against Russian and Austrian forces. With the successful conclusion of that war he was put in charge of the Polish Danube Legion which had fought from the Alpine mountains to the banks of the Po River. Still no special recognition or reward from Napoleon. Jablonowski’s three- month command ended with the onset of peace. Seen as redundant, the Legion was disbanded and, to Jablonowski’s further chagrin, not allowed incorporation into the French army and its troops, officers included, were denied French citizenship.

His military pay substantially reduced, he was forced to move to Passy, the Paris district residence of his fiancée, the adoring and generous Anna Barbara Pênot de Loney, who paid off his debts. On the edge of despair, a sudden change of fortune occurred and he was ordered to report for active duty, ready for deployment abroad. There are two accounts of what brought about Jablonowski’s promotion to Brigadier General. The first and most often repeated version is that it happened because Jablonowski made a personal appeal to Napoleon, his former classmate, tormentor, and now France’s First Consul, to make him a general in the regular army. But noted Polish researcher Sławomir Zagórski asserts that it was the intervention of Polish general Jan Henryk Dąbrowski and French general Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, who pressured the First Consul to grant the long overdue upgrade. Laying aside the question of who was most responsible for the promotion of a valiant and worthy officer, the act itself served the private desire of Napoleon, a master of artifice and manipulation, who viewed it as the solution to finally rid himself of someone he never liked or trusted.

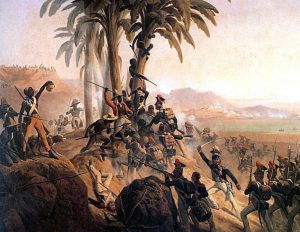

Determined to improve his financial situation, the newly decorated Black general was only given the possibility of advancing his career provided he shipped off to France’s possessions in the Americas. He could either guard Louisiana or help suppress the Black rebellion in Saint-Domingue (Haiti). War minister Louis-Alexandre Berthier recommended to Napoleon that Jablonowski be posted to the nightmarish deathtrap of Saint-Domingue. Napoleon gladly assented.

Jablonowski, along with his two adjutants, his secretary, and his devoted Anna, arrived at Le Cap in August 1802. Blinded by ambition, the quest for glory, and the possibility of gaining wealth and a secure future, he scarcely considered the cause of the colony’s Black inhabitants who fought for emancipation and independence. He had always proudly self-identified first and foremost as being Polish, not French, nor Black. The details of his few, unremarkable military actions during his one month in the colony need not be summarized here.

Like many of the 5,400 Polish legionnaires deployed to Saint-Domingue who avoided merciless slaughter but instead died of tropical diseases, Jablonowski, at age 33, died from yellow fever on September 29, 1802 in the coastal town of Jérémie. Perhaps like the 400 Poles who switched sides and fought alongside the former Black slaves or settled there after Napoleon’s colonial army was routed, Jablonowski, having risked his life numerous times for France, had he lived a bit longer, might also have had second thoughts about his allegiance to a diminutive, egocentric warmonger and a nation that failed to rescue his beloved Poland. But on this we can only surmise.

Jablonowski is immortalized as “Polish and noble” in Wacław Gąsiorowski’s 1904 novel The Black General. And he is commemorated in the acclaimed epic poem Pan Tadeusz by Polish Romantic poet-political activist Adam Bernard Mickiewicz, excerpted here:

How Jablonowski had reached the land where the pepper grows

And where sugar is produced, and where in eternal spring

Bloom fragrant woods; with the legion of the Danube there

The Polish general smites the negroes, but sighs for his native soil.