A Mother’s Personal Journey to Shame

Written by Karina Simonson

Writing from Lithuania, academic Karina Simonson critically reflects on why she felt having a mixed-race son affords her legitimacy as a white scholar of African culture and history.

“Mummy, it’s my land! What are you, white people, doing here?” These were some of the first words my son said after landing at the OR Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg this February.

I am an academic and an art historian whose research focus is on a number of diverse historical topics, including South African Jewish photography, historical connections between Lithuania and African countries, and issues of race and racism in Eastern Europe. What this means is that I am constantly reflecting on the rights and competencies of a Lithuanian academic, maybe even Europeans in general, to talk definitively about African culture and history. Is there a way by which one could earn such a right? Would having a member of one’s family belonging to the culture about which one seeks to comment give one legitimacy? At times I think it does help. I know this will raise some eyebrows but please allow me to continue.

Multiracial families, in which various members may under certain circumstances be classified in different racial categories, are relatively common. I happen to belong to one. Such families have interesting dynamics of their own, especially when they interact with the broader public.

There is something to be said about the ‘alchemy of race’, in that it can be a powerfully transformative tool; for better or worse. I witnessed this on a recent family trip to the Middle East when my son, who is a person of colour, but not particularly Middle Eastern looking, was nonetheless accepted as part of the culture. Complete strangers happily engaged him in conversation and many were kind and generous with sweets and gifts, and he could even walk freely into the mosques. I, as white person, did seem somewhat out of place, even when standing next to him, but I was nonetheless accepted as his companion.

A new generation of mixed-race kids in Lithuania

Now let us explore this issue for Vilnius. I understand that some readers may be curious to know how many mixed-race children there are in Lithuania, keeping in mind that the country is not on the map for any significant African diaspora. The local African community counts a few hundred, with people originating from different countries, mostly Nigeria, but also from Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Namibia, the Comoros Islands and others. Many of them have married locals and are raising mixed-race kids.

Other families consist of single Lithuanian mothers. In such cases, it is often that the mother was working somewhere in Western Europe (mostly UK, Sweden and Norway), had a relationship there and it did not work out, then she returned to Lithuania with one or more children. Just in our courtyard there are three children born to such families, and another three in my son’s school.

There are various strategies and approaches that people have taken for raising mixed-race children. Some parents are more conscientious about the issue of race in the way they raise their children. Such parents will, for example, order children’s books from the UK in which black kids are playing leading roles in the narrative of the story. They may even on occasion organise special gatherings for families raising mixed-race children. On the other hand, some parents do not pay much attention to the issue of race and therefore will not do anything differently from any other Lithuanian family.

The majority of Lithuanian mixed-race children are still quite young, mostly under 12 years old. Therefore, we do not know yet what the public reaction will be to brown teenagers, in the way these problems exist in the West. During the recent Black Lives Matter marches in Vilnius, only a 17-year-old named Clyde of mixed British Caribbean/Lithuanian heritage made himself vocal.

The bond between parent and child is truly special and unique, I may even call it sacred. The kind of language that connects a parent to a child is often untranslatable outside the context of that relationship. I reflect on my child’s race and have adopted the attitude that I need to be open to him about it. Yet, somehow it is not in racial terms that I engage my son, it is rather in the way that any mother would connect with her child. When I call him, ‘my sweet chocolate’, it is not a label but rather a relationship. It is my way, our way, of connecting, laughing, loving and being with each other. I know this is a nuanced and a subtle point to make, and I expect it to be so because I am trying to express something of that sacred bond between mother and child. I hope one day, if the world should remind him of his race, then he might also know that in my embrace of him, his identity was included, irrespective of what label the world gives him.

South Africa as a point of departure

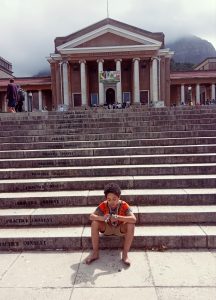

South Africa’s legacy of apartheid, in which racism was codified in a set of laws that oppressed black people, makes it the crucible for what I earlier referred to as the ‘alchemy of race’. It is a country I am quite familiar with because I studied there at the University of Cape Town for two years and continue to work on some research topics related to the country. In February of 2020 I was invited to present a paper at an academic conference in Cape Town. Since the conference would only last three days, I used the opportunity to take some holidayand spend two weeks with my son there as part of an extended visit. It was his first visit to the continent.

It was during our time in South Africa that I realised I felt proud of walking down the street with my son; going to museums and visiting my alma mater. He came with me to all my meetings with friends and colleagues. I then wondered about my own sense of unmerited pride. It was as though I was treating his identity as some kind of achievement. My son seemed to be a way in which I could gain a voice or even credibility to speak about race. He was my ‘pass’.

It took me months of quarantine back home to unravel the multi-layered complexity of my feelings about being a white scholar of African studies. At the depth of this complexity was a nagging feeling that maybe I do not feel I am ‘good enough’ to connect in any meaningful way with the very subject for which I am supposedly an expert in, and I was using my son as some kind of ‘human shield’. Maybe as a hintergedanken I felt that without my mixed-race son I could not be accepted, taken seriously, trusted or even be worthy of friendship. Having him gave me the ‘right’ to do my research.

I feel happy now that finally have unravelled this. I am extremely critical and deeply ashamed of my behaviour, and am sure it doesn’t add me any credibility as an academic in African Studies. But in everyday life, during travels, amongst old and new friends, my son is a blessing helping me to see things that otherwise I would not be able to.