Behold, I Am Here: Juan de Pareja’s Remarkable Self-Portrait

Written by Robert Fikes, Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

In discussions and biographies of the highly regarded Baroque Afro-Spanish artist Juan de Pareja it is routinely overlooked that he painted the first ever self-portrait attributed to an artist of African descent, a rather amazing occurrence in an age of growing commerce in slaves. And a unique set of circumstances that brought about Pareja’s other artistic triumphs deserve our consideration and comment.

The genre of self-portraiture essentially did not exist until the Renaissance with its humanistic emphasis on the individual and artistic expression. Thanks also in large part to improved mirrors, in the 1660s a number of leading artists drew or painted themselves, including van Eyck, Caravaggio, Rubens, Velázquez, and Rembrandt. The artist could paint himself as a solitary subject or insert his image in a crowd. The motivation to attempt a self-portrait could be to memorialize oneself, reveal some deeper aspects of personality, confirm authorship, model talent to prospective clients, or it might evince sheer egotism. Facial details were not necessarily meant to be exact – a reasonable approximation might suffice depending on the inclinations of the artist.

By circa 1606, the probable year of Pareja’s birth to a Black woman named Zulema and a native Spaniard, more than 250,000 slaves mainly from North Africa and coastal West Africa inhabited the Iberian Peninsula. They were prohibited to work in certain skilled professions but the process of miscegenation and acculturation proved inexorable. Because slave status was not necessarily heritable, the occurrence of manumission more frequent than in the Americas, and skin colour in the 16th and 17th centuries much less socially determinative than religion or wealth, it was possible for African-descended Spaniards to succeed independently, among them the lawyer Leonardo Ortiz, painter Sebastian Gomez and, most notably, Pareja and professor-poet Juan Latino.

Some myths and questions persist concerning Pareja’s city of birth (Antequera or Seville), birth year (1606 or 1610), and the conditions of his servitude over the many years he worked assisting the premier artist in Spain, Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, who was employed in the court of King Philip IV. With or without the awareness or permission of Velázquez, Pareja played close attention to his master’s preparations and techniques well enough to dare practice painting his own compositions. Literate, artistically gifted, and ambitious, he was more than a studio assistant (some contend he was never a designated apprentice): he was a trusted friend who signed and witnessed important documents for Velázquez and, in stretches of absence from home, Velázquez relied on Pareja to look after his family.

In 1650, Velázquez was accompanied by Pareja on a trip to Rome to paint the official portrait of Pope Innocent X. In preparation for the event, Velázquez had Pareja sit for a half body portrait which was then shown to local aristocrats who were quite impressed with its striking resemblance to his assistant. Often described as strangely haunting and mesmerizing, this ‘practice portrait’ of a dignified, congenial black man, whose warm eyes gazes back at the viewer (currently on permanent display at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art), today is widely esteemed as one of the finest examples of portraiture in the entire history of Western art.

But the main focus here is not a discussion of Velázquez’s motives for creating so flattering a likeness of Pareja or its superior workmanship extolled for nearly four centuries. Instead, we leap ahead to 1661, seven years after Velázquez is said to have released Pareja from bondage. Now a free resident of Madrid, Pareja had established a reputation as someone who excelled not only in portraiture (e.g., ‘Portrait of a Monk’ in 1651, ‘Portrait of the Architect José Ratés Dalmau’ in 1660) but also for adeptly rendering historical and religious scenes (‘Flight to Egypt’ and ‘The Immaculate Conception’ both in 1658).

There is near unanimous agreement that Pareja’s career masterpiece is ‘The Calling of St. Matthew’ (1661). Housed in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, the massive oil on canvas painting, measuring 7 feet by 10½ feet, was inspired by the New Testament Bible book of Matthew, chapter 9 verse 9: “(Jesus) saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. ‘Follow me,’ he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him.” Devout Christians could readily identify two figures in the scene: an oddly dispassionate Jesus at the right end of the table issuing the command, and Matthew who sat at the table next to him, hand touching his chest as if startled as he stares up at the Saviour. Also at the table are two ostensibly prosperous men dressed in the high fashion of the day. Anonymous persons surround the table and populate the background.

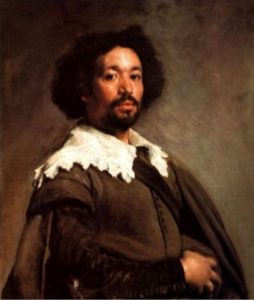

Farthest from Christ at the left margin of the scene stands a man of darker hue – the only person staring directly at spectators. This is Juan de Pareja, not as Velázquez had presented him as an assistant and travel companion in 1650, but as Pareja saw himself and as he desired to be seen by others eleven years later.

Modestly attired like in Velázquez’s portrait of him, he wears a plain, dark doublet and jerkin, unadorned white collar and sword belt. Some contemporary art critics have accused Pareja of having lightened his skin tone a bit in an effort to downplay his African heritage, but the alteration appears only slight. Though in his 50s when he painted himself his face is that of a younger man (Velázquez’s portrait of Pareja also subtracted several years). His body frame is slimer and, based on the length of his arms and torso, likely taller than Velázquez suggested. His facial expression—calm but alert—befits a more narrow, oval shaped head. His nose is longer and more pointed and his moustache has been trimmed in the style favoured by the nobility, but his hair texture and soft, fixed stare recalls what we see in the Velázquez portrait. Pareja does not pretend to be a wealthy patrician. In relation to other males in the scene he seems aloof. He is not engaged with the taxmen at the table and even fails to acknowledge the presence of the Son of God.

A pale-faced gentleman standing next to Pareja has his head turned toward the artist directing our attention to him. To further draw attention to himself Pareja positioned a large golden plate behind his head that mimics a halo, something that would not have gone unnoticed in a period of intense religiosity. Far from wanting to blend into the tableau, Pareja purposely isolated himself in order to extend a special invitation and convey a message to every viewer, one that announces: “Behold, I am here, see me, the man who painted this astonishing scene. Marvel at my artistry and remember me”.

Neither an indelicate display of vanity nor a sure indicator of hubris, his decision to insert a full body portrait of himself in the scene was primarily a deliberate act of self-promotion. Not seeking to immortalize himself or overly concerned about posterity, in effect he offered a business card advertising his proficiency. Removing any doubt that he’s an employable master craftsman for hire, in his left hand he holds a slip of paper that reads: ‘Juan de Pareja in the year 1661’. Of his self-portrayal one is left with the general impression of a proud man of substance and intelligence who was supremely confident in his abilities.

Across the Atlantic Ocean in the Americas, we find no comparable Black or mixed race artist. Pareja’s historic achievement of a self-portrait was not duplicated there until 178 years later when Julien Hudson, a ‘free man of colour’ in New Orleans, state of Louisiana, painted himself in 1839. The same year Pareja elegantly inserted himself into a religious painting Virginia became the first British colony to legally establish slavery and the first permanent British settlement in Africa was established at Fort James at the mouth of the Gambia River.

Considering his humble beginnings Pareja was extremely fortunate to have benefitted from labouring in the ateliers of Velázquez, who died in 1660, and subsequently Velázquez’s son-in-law, the royal court painter Juan Battista del Mazo. Pareja towers above all Black artists known to be in Europe up to his time and well beyond, including his two contemporaries: Sebastian Gomez of Seville, once a slave of the estimable Bartolomé Esteban Murillo who instructed him, and the obscure (maybe fanciful) Afro-Austrian painter Higiemonte Indus.

In writing a synopsis pertaining to Pareja’s recently discovered ‘The Hound of Saint Dominic’,a researcher for the high end international art dealer Robilant+Voener asserted: “In a society obsessed with pure lineage and hostile towards Jews, Muslims, converts, and those of mixed race, Pareja’s success is remarkable.” The oeuvre of Juan de Pareja, capped with his stunning ‘The Calling of St. Matthew’, secured him a niche in the pantheon of Baroque ‘Old Masters’. But there are two things, almost never recognized, for which he should also be credited. Most significant, he executed the first known self-portrait by a person of Black/African ancestry. From Dürer to Rembrandt to Delacroix – Renaissance to Baroque to Romantic eras – white Europeans who sketched or painted portraits of Blacks usually did not bother to identify them by name, the inference being it wasn’t important to give the name of someone held to be of inferior social status. Pareja, an independent professional of distinction, was glad to display his name on a work of art for the world to see . . . and speak silently but eloquently to those who contemplate his exquisite creations.

“historic achievement of a self-portrait was not duplicated there until 178 years later when Julien Hudson, a ‘free man of colour’” ..is this a surprise? black people were enslaved. And being “free” still was not truly free – lacking resources.

“Pareja was extremely fortunate to have benefitted from labouring in the ateliers of Velázquez” makes sense in comparison to the living conditions of many other slaves, yet let us not put his white master on a pedestal.

“he executed the first known self-portrait by a person of Black/African ancestry” according to the history of European/Western art.

This article seems to uphold European history as the standard, and fails to acknowledge the difficulties black people faced during this time. Of course there haven’t been many artists of African descent making waves anywhere. How could they given the circumstances? This article could have better reflected the system (colonialism, slavery, imperialism) that led to the situation of the artist Juan de Pareja in the first place, rather than exalting the individual’s achievement within a world resigned to white European dominance. Of course, it is incredible that he overcame his circumstances. I just wish this article reflected those circumstances. The quotes taken from the article above particularly highlight my point.

This is really fascinating history and helps to expand the lens on who artists always have been-diverse, people of color, women , and from all walks of life. What a pity that racism and white supremacy has kept the work of so many hidden and out of sight even when they worked within the standards of European art. In the telling of Pareja’s story let us be open about his status- he was a slave and not a studio assistant. How many European artists would have survived that much less go on to produce work of high merit? Let’s stop white washing history, and darn it Velasquez owned a human being. That is dissappointing.

¿Porqué los anglosajones tenéis la manía de juzgar el pasado con los ojos del presente? Cuánta mojigatería. (Why the anglosaxons used to judge the past across the eyes of the present times?)

My brother recommended I might like this website. He was entirely right. This post actually made my day. You can not imagine just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!