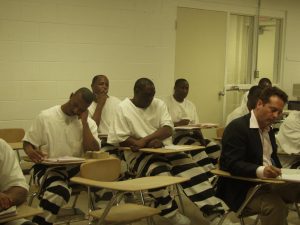

Book Review: Unit 29-Writing from Parchman Prison

Within the first few pages, Unit 29 – a collection of writings by inmates from the infamous US Parchman Prison, brought me to tears. And yet, not for the reasons you might expect. What I witnessed in these pages was a depth of humanity, seldom witnessed in other contemporary literature. Contributors to Unit 29 describe their daily lives in Parchman, a prison notorious for human rights violations due to the egregious level of infrastructural neglect. Between these pages, which include poetry, short stories, prose and journal entries, the writers display their hopes, dreams, frustrations, and every other emotion common to the human condition. Put quite simply, this is not a piece for the faint of heart. But that’s a good thing.

To understand the gravity of the words written in this book, some context about Parchman and the U.S. prison system within which it operates is crucial. Parchman Prison is a maximum security prison located in the unincorporated Parchman, Mississippi. As has been previously reported on Afropean.com, Parchman is notorious for human rights violations due to years of defunding and neglect. The abhorrent conditions, and deteriorated infrastructure led to riots that boiled over in 2020. In response, the Department of Justice opened a civil rights investigation, which led to a 2022 report that found the prison’s conditions contravened the Constitution.

The Mississippi Centre for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica reported on increases in grisly violence, gang control and substandard living conditions. Apparently, the authorities in Mississippi had known about these issues for years, but somehow never made it a priority to improve the constitution-violating conditions. This context underscores the sentiments expressed in Unit 29, imbuing a poignancy to the words.

‘Our happiness doesn’t matter, we are not human to them or society.’ Nathan Sumrall from My Life in Prison

Resilience in Repetition

What does it take for a human being to adjust to the worst conditions, to the point of attaining remarkable and graceful resilience?

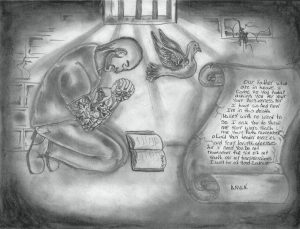

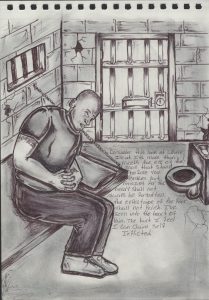

Surviving the horrid, unimaginable conditions at Parchman, let alone enduring a life sentence, forces one to contemplate the meaning of their existence. In Repetition is Life, Leon Johnson describes a meditative, graceful way of prison living. Waking up at an hour long before sunrise, he begins with gratitude to God for surviving another day, as well as praying about ‘the many devastating problems we have in this confused world’. He describes his breakfast, mentioning that he eats oatmeal ‘because of the fibre’. He still enjoys it the very same way his mother used to prepare it for him as a child; with sugar, butter and milk.

Then Johnson begins his job cleaning various bathrooms in the administration building, describing the meticulous steps. He never cuts corners. ‘When you do something, do it right’. It seems Leon has unlocked a level of wisdom many of us strive for, yet few achieve. The simplicity of finding solace in routine, in repetition and managing to find some level of satisfaction within that structure is something people pay thousands of dollars at retreats and workshops to find. By contrast, devoid of those privileges, Johnson has managed to find serenity and contentment in some of the worst living conditions imaginable. And yet, for Leon, ‘It’s just another day’.

Forgiveness

‘Why can’t I have another chance? What happened to not repaying evil with evil? Why can’t any of us with life sentences have another chance?’ surmises Nathan Sumrall in My Life in Prison. And I’m inclined to agree. Given that the U.S. is a country that so complacently rests on its so-called Christian morals, why do we seem so averse to actually practising and applying those morals within our justice system? Surely this is not the way Jesus would have dealt with crime. Part of the reason we can’t seem to adhere to our stated morals is due to, like many problems in the U.S., racism and our history of chattel slavery.

There are major discrepancies in the way the law is applied among certain demographics within the U.S.; race being the obvious one, but also class. The justice system in the U.S. theoretically functions to protect a democratic, free country. In reality, it serves to protect the interests of capitalists and maintain hierarchies along class and race lines. The history of the U.S. justice system stems from slavery, like many of our modern-day structures. The police act as surveillance and patrollers, ready to capture any runaway slave/civilian, and then they are hauled away, detained, and isolated from their community for an arbitrary amount of time.

The U.S. lives this double-consciousness reality when it comes to forgiving crimes, especially murder. We allow certain groups, such as police, soldiers and disgruntled white teenagers, to commit murder, while punishing other groups (such as via abortion bans) for committing the same crimes. We define the criminals before we define the crime.

The writing in Unit 29 should be read by everyone, everywhere, especially those of us in the U.S.; a country with an ever-increasing surveillance state and proto-facism setting in. The line between civilian and criminal is becoming thinner and thinner by the day, especially if you belong to a marginalised group. By reading Unit 29, my hope is that these words serve to humanise the individuals incarcerated at Parchman and other prisons, and that in turn, we see more clearly the unjust systems by which they – as well as the rest of us – are impacted.

References:

Please follow the link for more information on how to purchase Unit 29.

Absolutely gorgeous writing

Great read!