Border Crossings: Travelling Whilst White

Written by Nat Illumine

Last month I set off on a work trip to Amsterdam with my co-editor Johny Pitts. We had been invited on a recce to meet with a representative of The Holland Festival who have booked Afropean to curate an event as part of their performing arts month-long festival in June. It was to be a short trip – leaving London on Monday morning on the Eurostar via Brussels and returning the same route Tuesday evening – and we had a number of meetings planned: at the venue, the production office, the Black Archives. I’m normally meticulously organised, and after dropping off my child at school, I set off for St. Pancras International armed with everything I needed for the trip – or so I thought.

Upon arrival at the station, as I put my case through baggage security, and looked ahead at the immigration line, I realised the unthinkable – I had forgotten the most important piece of travel kit of all – my passport. I had that moment of sheer panic; I’m not going to be able to get on this train… Johny will have to go alone… should I run home and book a flight!? I felt mortified at letting my colleagues down. A baggage handler stood before me and I said to him, “oh my God, I’ve forgotten my passport, what can I do?” He told me to get someone to send me a photo of it on WhatsApp, and fortunately my housemate was still at home, so I had her do so. I walked up to the immigration official, utterly embarrassed (especially as Johny had just rolled up in an adjacent queue) and asked her if I’d be able to board the train with a poor scan of my passport and my driving license – both of which I know are not considered eligible as travel documents.

The immigration official called a supervisor, and with my sweetest smile, I asked him if I could travel. I told him it was a short work trip, and I couldn’t afford to miss it. He told me that there was another train five hours later, so I could return home for my passport. He was a white man around the same age as I, and our interaction was friendly, and so I pleaded with him to let me board the train, knowing I didn’t want to miss any of the meetings. He said that technically he could let me board the Eurostar, however he wasn’t convinced I’d be able to return the following day. I told him I’d chance it. He said we needed to speak to the French captain, who was also a white man. Both officials were extremely friendly and generous towards me, and after a few minutes’ discussion, I was told I could board the train but that, should I experience any difficulties on my return, the conversations between us had not happened.

Relieved, I joined Johny and we began our journey, both amazed at how I’d blagged my way across an international border without a valid travel document. But I knew why I had been able to do so. I was a young-looking white woman, with a middle-class, British, London-based accent, a diminutive frame, and a winning smile. I was the perceived antithesis of what is portrayed as a potential threat to national security. Firstly, I wasn’t a man. But more importantly I believe, I wasn’t perceived as an ethnic minority. I am an ethnic minority, a second-generation Eastern European Jewish immigrant, however I routinely pass for white British. The constructs of race, gender, class and appearance had all played their role in this interaction, both mine and those of the officials, resulting in my being able to utilise these forms of privilege to my advantage. I have never felt so keenly the value of my white skin in lieu of an actual passport.

I spent much of the train journey pondering this. Of course, I have no evidence that any of these constructs played a definitive role in the successful outcome of the situation, but as a race scholar, I knew in my heart what was happening, and although grateful I was able to continue on my journey, I was equally troubled by how it had played out. Had it been Johny who had forgotten his passport, a tall, mixed race man, with a working class Sheffield accent, I doubt we would have been able to continue our journey. I wonder how it may have played out had I had my child with me? A brown-skinned child with an afro, whom I’ve had issues with immigration officials before on account of our different last names. I wonder how it will be for her travelling as an adult with an obviously African surname.

I posted the following status to my social media accounts:

So I turned up to the Eurostar at Kings Cross to get a train to Amsterdam for a work trip for Afropean without my passport! But I managed to persuade the supervisor and his senior to let me on the train. I would argue this is a great of example of race, gender and class privilege (and perhaps a winning smile), as if it had been my mixed race male business partner I’m not sure we’d be in the same boat (or train, as it were). Let’s see if I can make it back into the UK tomorrow on the same basis.

I received about 40 comments from friends, all amazed that I had managed to blag my way across the border. A black female friend of mine responded that “race trumps gender… take it from a black girl who used to live in Brussels”. She too had forgotten her passport:

I had just returned from Germany the day before but had decided to wear another jacket on this trip. One of the Eurostar team came to assist me and when I explained she said there was no way I could travel, “impossible” in fact, and said I’d have to go home and retrieve my passport (which was an hour and 10 minutes away). I absolutely had to be there that night so had no choice but to go all the way back home, grab my passport and return. By then it was Friday evening rush hour and it soon became clear that there was no way I was going to catch that train. As check in closed I was ten minutes away. So, what to do? I collected my car, upgraded my AA cover, filled the tank and drove my ass for five hours to Brussels.

An Indian female friend of mine was also prevented from boarding a train under similar circumstances. However, a black male friend told me that a white girl had once visited him from Denmark without a return flight and had just popped up at the airport and asked to be flown home and was duly put on a plane. This seems legitimately outrageous, and quite frankly, unbelievable.

I had a number of white friends make comments such as “it’s that innocent face of yours” and “I think it’s just you Nat, nothing to do with gender or race, you’re just lovely” but I don’t agree with them. It’s easy for white women to fail to recognise their privilege when it has never been made apparent to them. But as editor of Afropean, and as the British-born daughter of an asylum-seeker, I know full well the implications of my privilege. One only has to read Zdena Mtetwa-Middernacht’s account of her experiences travelling the Brussels-South Africa route ‘Black Skin White Borders’ to realise the ramifications of race in the context of international travel.

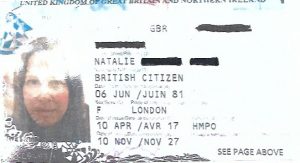

Many people warned me that it would be harder on the return journey, and I was anxious about returning the following day, but I needn’t have been. I rocked up to the Eurostar at Brussels now armed with a printout of the scan (although a really poor copy, as seen above) and my driving license and all was fine. The Brussels official laughed at my admission of having forgotten my passport and waved me on to the UKBA official. A middle-aged white man, he told me it wouldn’t be a problem, requested another official do a DVLA check on my license, and I was sent through within five minutes. Piece of cake. The ease at which I was able to traverse international borders without an official travel document was astonishing and unsettling.

Others I spoke with who had difficulties crossing borders for various reasons did not feel that their race or ethnicity had played a part. Clearly, no one individual will necessarily experience the exact same thing in these cases. The factors of race, gender, class, nationality and appearance will play out in different ways at different times. However, I refute the idea that I was just lucky. These constructs were mitigating factors in the ease of which I was able to travel, and I believe the race and gender of the officials I interacted with at each stage also impacted the result. I see my privilege. I have always seen it, but this was the most tangible example I have ever experienced. The paradox here is that I was both grateful and yet, angry. Angry that my white skin makes allowances for me that those without do not benefit from, and not only do they not benefit from, but they actually have their life chances and wellbeing impinged because of this on a regular basis.

What’s poignant about having just had this experience is that whiteness is a key research area of mine, and I am currently finishing up a five-part essay for Afropean, analysing a number of facets of the construction of whiteness, including white privilege. I am fully cognizant of how my whiteness plays out in my day to day, but never has it been made so flagrantly apparent as this.

Afropean invites our readers to both respond to this article and contribute their own experiences travelling across borders by emailing nat@afropean.com

Thanks Nat for the thoughtful and self-aware article. I agree with your friend that race trumps gender. I made the same error travelling to France 20 odd years ago. I was in my late teens. By some miracle, I had no trouble getting into France for reasons I cannot recall. I just don’t think it came up. Perhaps Eurostar was more lax back then. This was still the day when you travelled via Waterloo.

However, the return journey from France to Britain was another matter. Long story short, I was taken aside and held up until an official called the British Embassy to verify I was legit. Come to think of it, the same thing happened a mere few months ago crossing the German border from France by coach. (You don’t instinctively think of taking your passport when going by road). We couldn’t move until the Embassy had been contacted.

The other dimension to this is having a UK passport. It’s like the cachet of it mitigates the ‘stigma’ of my dark brown skin. It’s a bit of a mind-warp because a part of me hates the covering that it affords me. My maternal grandmother insisted on travelling with her Nigerian passport, despite her British citizenship. I recall some hairy moments at airports, being randomly called aside. Chimamanda Adichie famously does the same.

I think this all goes to highlight the constructs around people of certain ethnicities and how much this is steeped in economics; i.e. capitalism. The UK is a comparatively wealthy country (notwithstanding that the wealth is highly concentrated according to region etc). Wealth is associated with lighter skin and all the associated privileges…

Hi Tolita,

Thank you for your comment. I agree having a British passport mitigates stigma in a way that is paradoxically beneficial and problematic. As a second generation Jewish immigrant from the Czech Republic, I have often felt gratitude for my British passport and the opportunities living in London and the UK has afforded me (compared to living in the tiny Czech village where my family are from) but ultimately it affords me immense privileges that so many do not have the luxury of, and it’s difficult, if not impossible to reconcile feelings of gratitude with an awareness of unearned privilege. Something to muse on.

Wishing you the best and luck in all future travels! Thanks, Nat

I gotta bookmark this web site it seems very beneficial invaluable

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new surveys are added- checkbox and already each time a comment is added I receive four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can eliminate me from that service? Thanks!