Lost in Otherness: Growing up as a mixed raced child in Eastern Europe

By Nina

Whenever someone asks me where I come from, answering ‘Slovakia’ always evokes a surprised reaction, no matter if it happens abroad or back home. Even though nowadays the borders are open, Eastern Europe is still the last place anyone would expect to find a mixed race or black person. In fact, we are still a rare sight on the streets and literally invisible everywhere else, because there is no media which serves us as a racial minority and educates the public about black European culture. Eastern Europe has also always had a poor track record in terms of social integration. Thus the position of any person of colour in our society is still vulnerable.

Historically, countries like Slovakia have always been isolated, far from the melting pot of Western Europe. Ironically it was communism which opened the doors to foreigners from faraway lands through various exchange programmes for students and professionals. As a result, the local people got opportunities to meet foreigners from countries such as Vietnam or Cuba. Another paradox is that the regime was quite rigorous when it came to attitudes towards race, as it demanded the equal treatment for all and hate speech could be strictly punished. However, unlike in the multicultural countries of the West, the change over here has been a lot slower and, as a result, if someone does not look like the majority they will be reminded of their ‘otherness’ in many different ways. Sometimes it can be amusing or bizarre, other times it can come as a bit of a shock, reminding you that there is lot that needs to change in people’s minds.

Growing up I remember being the only different one everywhere. School, my group of friends, my closest family. For the most part, the people I knew personally treated me well, especially when talking to me face-to-face. I noticed that many would make an effort to not say things which would be insulting or inappropriate when they referred to my looks or my father’s origin. However, interaction with strangers was a different story. It felt as if I was suddenly part of a different reality. That I was not quite fitting this picture.

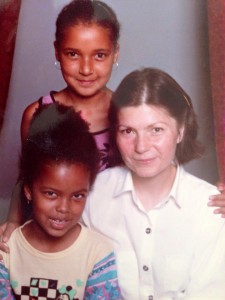

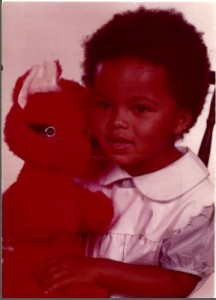

I remember being welcomed to my own home town by a person who was so fascinated by my looks that they somehow did not catch my remark ‘thank you, but I was born here’. Many people keep talking to me in English even when I respond to them in Slovak. When I was a baby, my mother told me that people would follow her when she went out with me in a pram so that they could catch a glimpse of me. I once met one of these curious passer-bys who, years later, asked me if I remembered her because she would walk behind my mother for a good half an hour looking at me.

Unpleasant experiences have included being openly told that I don’t fit the image of a Slovak person. I was and still am referred to as ‘exotic’ or ‘like that’ as if calling me what I really am is something negative. However, I have noticed that my appearance is the main reason why people want to interact with me. The negative statement which tops it all was an attempt to blame the racist behaviour of strangers on my mother who, according to some ignorant people, ‘hurt me’ by choosing a black man as my father. However, looking back, it was the unexpected remarks from family or people whom I considered to be my friends that stung the most. Everyone claims that they do not look at race but the occasional slip of a tongue proves that in their subconscious that is not so. Even after knowing me all these years.

Even though I grew up constantly associated with African culture, I actually knew little about it. After my parents’ marriage ended my father never introduced me to his culture and all I had were a few tapes of African music he left behind. There is no tuition of Black history in Slovak schools so I only had very limited information to work with. So, here I was – a black person who does not know anything about her blackness and yet is constantly reminded of it by society. It was puzzling, and still is. Looking back I now understand that I grew up without a clear sense of who I was in terms of my place in Slovak society and also in terms of understanding my individual identity.

I got used to the idea of being the only one everywhere, and without seeing people similar to me, I did not have enough motivation to explore any of these issues further, because it only aggravated the feeling of being a stranger. It was only when I moved abroad, to a multicultural country, that I started to seek other stories similar to mine. It is very comforting to find someone who has walked in your shoes and dealt with similar things growing up. Finally, I saw a reflection of myself in others and had a chance to discuss many topics which were at the back of my mind because I had no one to talk to.

To sum up, I think that Eastern Europe is not the kind of environment that a sensible person should choose for their mixed race child unless they have no other option. It’s simply not ready for us for two reasons: Firstly, times have changed. Whereas in the past it used to be relatively open and friendly, Slovakia nowadays is a country where most people have become ardent opponents of so called ‘political correctness gone mad’, therefore it is generally acceptable to put a lot more emphasis on differences than on traits that we have in common as people. Multiculturalism, which was never properly embraced, is now frowned upon. As a nation facing harsh economic conditions, Slovaks are becoming wary of everything outside of the ordinary. They no longer have trust in strangers. Secondly, a lack of education about racial tolerance makes it difficult to build bridges. Even though Slovakia has had an issue with race relations, the state still has not come up with an effective way of addressing it. The consequences of not having any such measures in place will always prompt people to be biased against those who do not look like them. The so-called protests against accepting refugees and fears of new migrants are a telling sign.

Don’t get me wrong, I think Eastern Europe can be friendly to a person of colour … but only if you are a visitor.

Follow Nina on Twitter