Not of Heaven: Black Cult Leaders of Mid-20th Century America

The best thing you can do for the poor is not to be one of them.— Rev. Ike, 1975

Pushed into action by frequent lynchings, harsh Jim Crow laws that ensured long-term racial discrimination and third-class citizenship, as well as recognising economic opportunities created by the exigencies of World War I, Black-Americans fled their largely impoverished homelands in the South to risk their futures in the industrialised urban centres – mainly in the North and Midwest. To the extent that, between 1910 and 1970, 6.5. million of them had settled in what they prayed would be their Promised Land. Scholars refer to this relocation en masse as the Great Migration. Though sometimes naïve, undereducated, and initially unprepared for the challenges of life in crowded ghettos, they were fortified with religious values which, unfortunately for some, proved to be something that could be exploited given the right circumstances.

Mainstream Black churches simply weren’t able to satisfy the spiritual and physical needs of such a crushing influx of emigrants. A segment of this Black religious community wanted a more tangible presence of a version of the Christian God in their lives; a flesh and bone, charismatic father figure they could see, touch, and hear directly from in order to know what they must do to earn the rewards of their obedience. A minister who received authority straight from the Supreme Being would suffice. Often feeling powerless to change their temporal predicament they deeply desired to be led; to belong to a dynamic movement of true believers like themselves. Therein they could discover a source of pride to make daily life in a grim environment more bearable.

When God Rode a Rolls-Royce, Christ a Cadillac, The Prophet a Limousine

Long before there were Black megachurches and televangelists preaching the “prosperity gospel”, there were widely known Black religious cult leaders whose heyday spanned four decades – from roughly 1930 to 1970. They were treated like ancient royalty by their followers, who hoped to receive miraculous healing and material wealth from them. The big three were Prophet Jones in Detroit, Daddy Grace in Massachusetts and elsewhere, and Father Divine in Harlem and Philadelphia. All had humble beginnings and little if any formal religious training. Nonetheless, their church branches stretched from coast to coast and there were reports of admirers and nascent congregations forming in England, Switzerland, Egypt, Austria, Liberia, France, Australia, Canada amongst others. There were at least a score of imitators scattered outside the South. However, none rivalled the big three, or had nearly as noticeable an impression on American popular culture.

Father Divine (a.k.a. God)

The first priority of every aspiring cult leader is to declare his church independent of any existing denomination. This frees him from oversight and permits him to act with impunity. In the case of George Baker (left), born the son of a poor sharecropper in South Carolina, the precondition for disassociation from established Black churches was well understood, since he had apprenticed under a less gifted cultist called Father Jehovah. He moved to New York City and eventually launched his cooperative International Peace Mission movement. Through this initiative, he had the foresight to attract disciples and good publicity during the darkest years of the Great Depression by feeding desperate victims of the worst economic downturn of the century. He also entertained them, provided employment in sundry businesses, gave them communal lodging, a space for emotional release and, of course, miraculous healing of everything from sore toes to cancer. What he lacked in physical appearance (barely 5 feet tall and bald), he compensated for with organisational skills, the ability to pull in white congregants, a concern for political participation, racial parity, a knack for financial management, and the ability to awe credulous devotees.

The first priority of every aspiring cult leader is to declare his church independent of any existing denomination. This frees him from oversight and permits him to act with impunity. In the case of George Baker (left), born the son of a poor sharecropper in South Carolina, the precondition for disassociation from established Black churches was well understood, since he had apprenticed under a less gifted cultist called Father Jehovah. He moved to New York City and eventually launched his cooperative International Peace Mission movement. Through this initiative, he had the foresight to attract disciples and good publicity during the darkest years of the Great Depression by feeding desperate victims of the worst economic downturn of the century. He also entertained them, provided employment in sundry businesses, gave them communal lodging, a space for emotional release and, of course, miraculous healing of everything from sore toes to cancer. What he lacked in physical appearance (barely 5 feet tall and bald), he compensated for with organisational skills, the ability to pull in white congregants, a concern for political participation, racial parity, a knack for financial management, and the ability to awe credulous devotees.

He exhorted a rather severe moral conduct from his flock, that included no sex and no marriage without his approval—though he himself was notoriously promiscuous and married twice—no swearing (the words “hello” and “Amsterdam” were banned), and no smoking and drinking liquors. His rather stunning success in growing a movement –that even brought in a few white converts – apparently encouraged him to adopt the honorific “Father Divine”.

He also started referring to himself as God, as did his followers. He enforced the sharing of a congregation’s resources and preached the power of “positive thinking” (premier songwriter Johnny Mercer attributed the idea for the title of his 1944 hit pop tune Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive to a Father Divine sermon). As if to boost their self-esteem he told an audience: ‘I am a Negro and God dwells in me. You are a Negro and you are like unto me. Therefore you are superior to [the] whites.’ He reasoned people near– worshipped him because: ‘I am their life’s substance. I am their energy and ambition. They recognise my deity as that which was in the imaginary heaven, and if they can only get a word with me, they feel they are in heaven.’

One can only speculate whether or not Father Divine honestly believed all that he spouted about his divinity. In 1932, he famously took responsibility for the death of a judge who dropped dead three days after the jurist pronounced Father Divine a fraudster and a ‘menace to society’. He subsequently sentenced him to a term in prison for disturbing the peace. He justified his divine retribution to a reporter saying: ‘I hated to do it.’ At the height of Father Divine’s holy reign he had a fleet of expensive, chauffeured automobiles, lived lavishly in a 32-room mansion in Woodmont, Pennsylvania, and purchased the tallest apartment building in New York City, all made possible by the labour and donations of his mostly working class, socially–marginalised cult members. At age 70 he had in his entourage several secretaries, among them a 20-year-old white Canadian, a “spotless virgin,” whom he married in 1946 with hardly any blowback.

Daddy Grace (a.k.a. Black Christ)

Whilst he consistently refused to self-identify as Black or African American, Marcelino Manuel da Graça, a native of the Cape Verde Islands, clearly saw the advantage of anglicising his name to Charles Manuel Grace. The world came to know him better as Daddy Grace, founder of the United House of Prayer for All People in the state of Massachusetts in 1919. Early on, the former railway cook achieved renown for his overflowing tent revivals, faith healings, mass baptisms, use of fire hoses, stirring brass bands, “Christian Saints” parades, and rousing sermons.

Unlike the personally conservative Father Divine with whom he competed for followers from the same demographic, Grace was far less concerned with philanthropy, political activism, or social justice. Instead of projecting stability with his attire he veered into cringeworthy eccentricity. Witness his 4-inch fingernails (sometimes painted red, white, and blue to emphasise his patriotism), long hair, and flashy suits. He delighted in having members of church task groups march about in an assortment of uniforms. Like Father Divine, Bishop Precious Sweet Daddy Grace also turned out to be a very competent empire builder, who used the considerable wealth generated from numerous churches and business ventures to invest in real estate. He put his name on a variety of consumer products produced by church businesses (e.g., Daddy Grace Soap, Daddy Grace Toothpaste, Daddy Grace Cookies, shoe polish, coffee, hair straightener and so on).

Travelling with his armed bodyguards in one of his Pierce-Arrows, Packards, or Cadillacs, he capped off a buying spree in 1958 with the purchase of an 85-room palace in suburban West Los Angeles, the latest of numerous properties he owned including a mansion in Havana, Cuba, and The Eldorado, a fashionable twin-towered apartment complex across from Manhattan’s Central Park. To those who idolised Daddy Grace, hailing him the “Black Christ”, these things did not appear to matter. Others who also discounted paternity, alimony, and tax evasion lawsuits filed against him could live vicariously through Daddy Grace and celebrate his worldly triumphs, the likes of which few Black men of the era were allowed to attain.

Prophet Jones (a.k.a. Messiah in Mink)

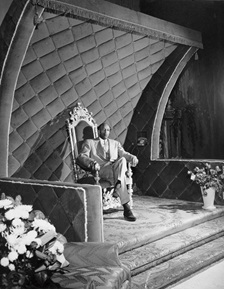

Without a doubt the most flamboyant, enigmatic, and perhaps tragic of the big three cult leaders was James Francis Marion Jones (right, circa 1952), whose ascending career crashed and burned at its peak. An elementary school drop-out in Birmingham, Alabama, he began prophesying and preaching in the Pentecostal tradition before reaching adolescence. After several years evangelising in the Midwest, he claimed God whispered in his left ear to start his own ministry in Detroit, which he did in 1944: the Church of the Universal Triumph, Dominion of God, Inc. Housed in a renovated movie theatre, it was guided by his 50 decrees and his idiosyncratic interpretation of the Bible. A pioneer in the use of mass media to spread his message, he delivered long-winded sermons over radio and for a while, could be seen on his weekly local television show.

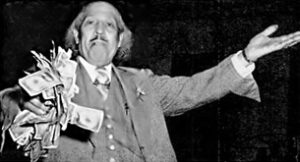

As money-obsessed as the other two cult leaders, he too became fabulously wealthy selling “blessed” trinkets at greatly inflated prices. He also sold photos of himself with numbers written on them that were supposed to bring good luck in gambling, charged a fee to those who sought a brief private audience with him and, as confirmed by congregants, regularly extorted money from groups of supplicants by locking church doors and refusing to release them until enough cash was offered to satisfy what he thought he deserved from them.

Prophet Jones lived in a 54-room grey stone French castle and gave royal titles like Arch-duke, Prince, Princess, Lord, and Lady to his subordinates because, he explained, ‘we are in God’s Kingdom.’ His castle contained enough clothing (including 400 suits and his treasured full-length white mink coat), fine jewellery, perfumes, and toys (a reminder of his impoverished youth) to stock a department store. Jones’ unusual lifestyle and ministry caught the attention of writers for the nation’s top magazines—Life, Time, Newsweek, and The Saturday Evening Post. The editors of Life thought Jones merited two separate feature stories. Its overwhelmingly white middle-class readership undoubtedly found details about these ministries to be bizarre, puzzling and amusing, with disturbing racial undercurrents. From Life, November, 1944:

‘When he appears in public they try to touch his car. When he requires something for his opulent home, his parishioners meet the need. A celibate, a teetotaler, and a mystic, Prophet Jones avowedly never reads secular literature lest his own inspired thoughts be corrupted by material concepts.’

The Sting of Disapproval

For I am the Lord thy God. You shall have no gods beside me.—Exodus 20:3

In a rare article of its kind in The Chicago Defender in 1939, Rev. Lacey Williams, President of the National Baptist Convention (NBC) tore into cultists, telling a large gathering: ‘We must indoctrinate our congregations and save them from their wild emotions. If we do this it will be impossible for Father Divine or anyone else to lead them off . . . I want to have nothing to do with these “morning glory religions”.’

The Black press seldom published hard-hitting criticism of the big three and, in contrast to its white counterpart, seemed more tolerant of their excesses, partly because of the potential of untold thousands of cult followers and the long-held fear of needlessly alienating natural allies who could be helpful in the overarching struggle against white racism. The popular Black weekly Jet magazine reported on the antics of the big three but never in a sarcastic or condescending manner, instead it let photos and numerous short articles expose their shortcomings. Only once, in November 1951, did Ebony magazine sanction a veiled criticism of Prophet Jones and others when New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. lamented the ‘tiny minority of degenerate ministers’.

Even the staid, mainstream clerics of the NBC, the largest Black supervising religious organisation, refrained from full frontal attacks of the big three, for it was plagued with its own internal problems and embarrassing publicity. Take for example what happened at its annual convention in Kansas City in 1961. The event was marred by the shocking death of Rev. A. G. Wright, reputed to be one of the wealthiest African-Americans in Michigan. After a fist fight amongst opposing factions broke out, Wright was either shoved or slipped off the stage and landed on his head. Police had difficulty getting the rioting reverends under control.

Writing in 1960 in the national edition of The Chicago Defender, poet-novelist Langston Hughes aimed for a balanced view of the ‘colourful personalities’ and their ‘unorthodox’ practice of Christianity. He quoted historians Carter G. Woodson, who characterised dispossessed cult members as being, ‘The hungry, the sick, and the heavy laden (who) have been asked to cast their troubles upon these divines and be free for evermore’; and John Hope Franklin, who described Father Divine’s operation being ‘as much a social movement as a religious development’. Once during his flirtation with communism in the late 1930s, novelist Richard Wright and a white party member visited one of Father Divine’s huge Peace Mission banquets for the downtrodden. He left chagrined, telling his comrade: ‘Oh whitey, deep down in your heart you think we’re dirt–this confirms your opinion of us’. A group of Black communists later opined in Negro Voice that Father Divine was ‘the most dangerous faker that thus far has appeared in Black America’.

Black nationalist Marcus Garvey was particularly annoyed with Father Divine’s stance on celibacy, charging that it was tantamount to ‘race suicide’. In 1944 Black anthropologist and civil rights activist Arthur Huff Fauset published Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults in the Urban North. He not only criticised cult leaders but also their enablers, i.e. cult members, as ‘gullible’ and ‘childlike’. He further implied that people should take pity and excuse their fascination with snappy uniforms and ostentatious displays of jewellery. More recently, Prof. Wilson Jeremiah Jones, author of Black Messiahs and Uncle Toms (1993), reached the harsh conclusion that the big three were essentially ‘opportunistic, egotistical charlatans who elevated themselves for purposes of self-aggrandisement’.

Twilight of the Gods

Father Divine: ‘I’m happy to meet you, your holiness’. Prophet Jones: ‘God bless you, your godliness’. -– said upon their meeting in 1953

There were recurring rumours of homosexuality levelled at both Father Divine and, more understandably, Prophet Jones. Suspicion fell on Father Divine because he advocated celibacy and routinely showcased his white “virgin wife” minus any children. In a more conservative era, to be outed as gay whilst in a leadership position meant instant career death. There had long been aspersions cast about the sexuality of Prophet Jones, who never married, had effeminate mannerisms and had had a long-term relationship with a much younger male assistant. The rumours were substantiated in 1956 when, in attempting to perform a sex act on an undercover policeman posing as a church member, he was arrested and charged with gross indecently. His cult never recovered. Moreover, his reputation as a prophet was ridiculed after he wrongly predicted that the Vietnam War would end quickly, that everyone alive in the year 2000 would become immortal and Earth would transform into Heaven. Most ridiculed of all was his claim that he had predicted the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan, when he observed steam rising from a piece of fried chicken. The Rt. Rev. Dr. James F. Jones, D.D. died from a heart attack in 1971 in Detroit. His iconic mink coat was draped over his bronze casket.

Whereas Father Divine, the most influential and prosperous of the big three, and Prophet Jones were on friendly terms—the latter hoping to inherit the older man’s ministry – Daddy Grace was an envious soul who regarded them not as brothers “in Christ” but as unwelcome competitors. Thus, when their operations faltered, he reportedly took spiteful pleasure in targeting and buying signature properties they had proudly owned. In January 1960 Marcelino Manuel da Graça, formally addressed as Bishop Charles Manuel Grace, died in Los Angeles. A 500-car motorcade escorted his hearse to Bedford, Massachusetts, where he was buried in a $20,000 glass-topped casket. At age 89 George Baker, formally addressed as Father Major Jealous Divine, died in Philadelphia in 1965. His white virgin widow, Edna Rose Ritching (a.k.a. Sweet Angel and Mother Divine, pictured above centre), inherited leadership of the cult and, to her credit, later prevented the infamous Jim Jones, instigator of the 1978 mass suicide in Guyana, from co-opting it.

As the final phase of the Great Migration ebbed and the social, educational, and economic status of Black Americans improved, new leaders emerged who were more focused on civil rights and politics. The demise of the big three resulted in the immediate, precipitous decline of their cults which could not be resuscitated to captivate masses of people willing to follow such brazen and outlandish individuals. They had directly affected the lives of hundreds of thousands, if not millions of African-Americans. But by 1970 the golden age of the Black cult leader was over and done.