Siyah: Haiti and the success of the Greek Independence Wars against the Ottomans

This is the fourth instalment in ‘Siyah’, a series which explores African Diaspora and Turkish social and cultural narratives, with journalist Adama Juldeh Munu. To mark 230 years since the Haitian Revolution began and 200 years since the culmination of the Greek War of Independence, the following article will summate Haiti’s support for Greek independence against the Ottoman Empire.

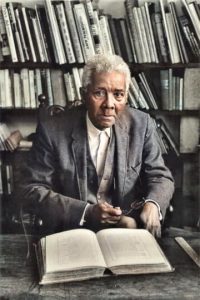

“It is Toussaint’s supreme merit that while he saw European civilisation as a valuable and necessary thing, and strove to lay its foundations among his people, he never had the illusion that it conferred any moral superiority…” ― C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution.

These words, penned by London-born Trinidadian C.L.R James in his ground-breaking work, reveals the less-than-simplistic relationship Haiti had with European powers under its first governor-general. That while Haiti’s forefathers took to Enlightenment philosophy and ideals associated with the French Revolution, its infamous and successful revolt against France served as a major source of inspiration for Greek nationalists who mounted one of the most direct threats to the Ottoman Empire’s influence in the early 19th century, the outcome of which led to Greek independence and its ongoing tense relationship with present-day Turkey today.

The Haitian Revolution was in one sense not exceptional for its time. It took place during an era that historians refer to as the ‘Age of Revolutions’, a spurt of turbulent political change in countries such as France, China and the United States, where insurrectionists were inspired by Enlightenment philosophy. In another sense, the Haitian Revolution was exceptional in its own right, not least because it transpired into the only successful slave revolt in world history (Leddy, 2004). Due to its emergence as the first independent Black majority country outside of Africa, and at the height of the transatlantic slave trade, the parameter for Black liberation was pushed beyond the scope of the African slave’s desire to be free from bondage to one to being a fully-fledged citizen with full self-determination and governance in a society of his or her own making.

The basis of revolutions is a reimagining of societal and political infrastructures. The ancient system of bondage was not a peculiar institution when it was first introduced to the colonies in what would later become a part of the United States of America, but social (white supremacist ideals) and economic (exploitation by way of capitalism) theories ushered in a new framework to justify chattel slavery. To say however that the Haitian Revolution was primarily pushed solely by L’Ouverture’s fascination with European ‘Enlightenment’ is only one part of the story. James’ argument primarily centres on the enslaved and their ‘allies’, their cultural and religious impetus for change, their collective mobilisation and the personality of Toussaint. And yet the call to freedom on this small island reverberated beyond its shores, inspiring and playing a role for other revolutionary movements, from Latin America to the Greek struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire. The latter raises some important considerations:

Click here to watch: Egalite for All: Toussaint Louverture & The Haitian Revolution

Firstly, learning about the relationship between Haiti and Greek nationalists somewhat detracts from the sole focus placed on the penultimate role the British Empire and Arab nationalists played in diminishing the Ottoman Empire’s power and influence.

Secondly, the different relationships that existed between various parts of the African diaspora and the Ottoman Empire is made apparent. Fleeing members from the island’s planter class carried tales that reached other parts of the Caribbean and the US, to the unsuspecting ears of other enslavers and the enslaved, including enslaved Black people who were emboldened by it. A fact that in 1893 abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass attested to when he described Haiti as “the original pioneer emancipator of the nineteenth century” in a lecture on Haiti:

“Until Haiti struck for freedom, the conscience of the Christian world slept profoundly over slavery. It was scarcely troubled even by a dream of this crime against justice and liberty… The mission of Haiti was to dispel this degradation and dangerous delusion, and to give to the world a new and true revelation of the Black man’s character. This mission she has performed and performed it well” (in Daley, ed., 2013).

Click here to watch: The Largest Slave Rebellion Was Hidden from U.S. History

Haiti’s demonstration of self-liberation was well known among antebellum African-Americans, who were further inspired to continue to revolt against their so-called slave masters. And while some historians are suspicious of the true extent to which Haiti played in inspiring such revolts, what is clear was that it was more than enough to rattle the most powerfully illustrious of the time, in countries like the US. Thomas Jefferson wrote to the governor of South Carolina on December 23 1793, saying he was informed by a French gentleman from Saint Domingue that two men of colour were setting out from the island to Charleston “with a design to excite an insurrection among the negroes” (Lipscomb, 1904). Also, several state governments created laws excluding West Indian Black people between 1792 and 1801 for fear the slaves of refugees (the slave planters) would ‘infect’ African-American slaves (Sheridan, 1982).

As Siyah: Deciphering the Ottoman Involvement in the African Slave Trade demonstrates, while millions of continental Africans for the most part served as the underbelly of the Ottoman Empire as slaves, Black diasporans in Haiti were actively working to undermine it.

But the discrepancy raises an important question and leads to the third consideration: Did knowledge of the social conditions of Africans impact Ottoman intellectuals’ reception of ideas linked to the French Revolution? In a discussion paper entitled ‘Between Saint-Domingue and the Sublime Porte: Revolution Ottoman Realpolitik, and the Inter-hemispheric contingencies of modern political thought’, Ariel Salzmann argues that there is textual evidence to suggest Ottoman officials like Secretary of State Mahmud Raif Efendi were aware of the strategic significance of Caribbean colonies and upheavals in a communique which he labels HAT 14217. This communique was devised at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It arrived in Istanbul on the eve of the signing of the Treaty of Amiens (March 25, 1802), which marked the restoration of Egypt to the Ottomans:

“Fransa Devleti’nin Amerika’da son Dominik [sic] adasında Tosi Lövernor [sic] ismindeki âsiyi tedip için Brest Limanı’ndan donanma sevkedeceği.” [Translation: The French Government will dispatch a fleet from the Port of Brest to the island “son Dominik” in America to put down a revolt in the name of “Tosi Lövernor”]

“When compared with the voluminous documentation to be found in the archives of Europe and the Caribbean itself concerning colonial administration, the trafficking in human beings from Africa, and the shiploads of commodities directed toward European ports and beyond, the absence of any explicit mention of slavery within the Ottoman document is in itself striking. Its writer did not comment on the fact that the slave revolt played out against the background of the ideas and politics of the French Revolution” (Salzmann, 2019).

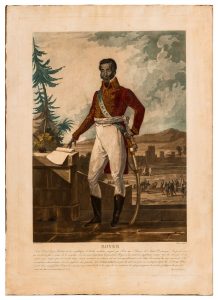

Salzmann suggests Ottoman officials may have not fully acknowledged the importance of the ideals underpinning the revolt; and that their idea of freedom would almost certainly have been limited to freedom from bondage as opposed to free citizenry. Fast forward to the period 1821-1830, the Ottoman Empire would be in direct conflict with these very ideals via Greek independence revolutionaries, marking an important juncture in its gradual decline and the political transformation of the Mediterranean writ-large. During the Greek War of Independence, revolutionary nationalists were in a struggle against the Ottoman Empire that had presided over the country from 1453. The outcome was the creation of modern Greece; the first subject peoples of the Ottoman Empire to secure recognition as a sovereign power. Their motto of ‘freedom or death’ was not quite unlike that used by Haitian revolutionaries. Revolutionary nationalists also faced a series of hurdles not too dissimilar to that of their Haitian counterparts. Early successes included the capture of Athens in June 1822, but by 1827, most of the Greek Isles had been recaptured by the Turks.

Greek nationalists sent a letter to Jean-Pierre Boyer, asking for ammunition and monetary support. Boyer was Haiti’s second president. He is remembered for his role in the unification of Haiti and the Dominican Republic – and his encouragement of free Black migration from the United States.

Freedom was hard-won, but it was fragile. Haiti’s sovereignty was thwarted by various power plays from France, Britain, Spain and the US which included threats of military invasion and ‘monetary’ compensation totalling 150 million francs, which is around $30 billion in today’s money. The extortion relates to a decree issued by France on April 17, 1825 that stated France would recognize Haitian independence at the price of 150 million francs. These led to the diminishment of the island’s wealth and political stability for decades to come. So, while the Haitian Revolution is regarded historically as a blueprint for Black liberation politics, Haiti was never allowed to blossom into a free and independent nation because of global structural racism, which is prevalent to this very day.

There was an important precedent in Greek nationalists seeking Haiti’s support. In 1815, after his defeat against Spain in Cartagena, Venezuelan revolutionary Simón Bolívar’s and a group of soldiers sought the aid of Haiti’s first president, Alexandre Pétion. Pétion not only provided shelter and food but supplied 4,000 rifles, gunpowder, military strategists and veterans for an expedition in April 1816. After the expedition failed, Haiti provided further supplies eight months later, whereby Bolívar succeeded. According to El Libertador: Writings of Simón Bolívar, a collection of public and private letters, Bolívar structured its first government and constitution after Haiti’s, and fulfilled a promise to Pétion to help other enslaved peoples in the region.

Bolívar wrote to Pétion that, “In my proclamation to the inhabitants of Venezuela and in the decrees, I have to issue concerning the slaves, I do not know if I am allowed to express the feelings of my heart to your Excellency and to leave to posterity an everlasting token of your philanthropy. I do not know, I say, if I must declare that you are the author of our liberty.”

Marlene L. Daut who is the Associate Director of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies tells me, “Significantly, Boyer saw the Greek independence movement as an extension of the one heralded by the Haitian revolutionaries in 1804, which culminated in Haiti’s freedom and independence from France.”

Below are extracts from Boyer’s response sent to Adamantios Korais, the Governor of Greece in 1822. As Sideris and Konsta explain, it “provides interesting insights into how the Haitian president viewed the role of Haiti in the world. At the same time, it highlights the allure Haitian revolutionaries had among contemporary Greek revolutionaries thousands of miles away.”

LIBERTE (The Hag) EGALITE JEAN PIERRE BOYER

President of Haiti

To the citizens of Greece A. Korais, K. Polychroniades, A. Bogorides and Ch. Klonaris In Paris

Before I received your letter from Paris, dated last August 20, the news about the revolution of your co-citizens against the despotism which lasted for about three centuries had already arrived here. With great enthusiasm we learned that Hellas was finally forced to take up arms in order to gain her freedom and the position that she once held among the nations of the world.

Such a beautiful and just case and, most importantly, the first successes which have accompanied it, cannot leave Haitians indifferent, for we, like the Hellenes, were for a long time subjected to a dishonorable slavery and finally, with our own chains, broke the head of tyranny.

Wishing to Heavens to protect the descendants of Leonidas, we thought to assist these brave warriors, if not with military forces and ammunition, at least with money, which will be useful for acquisition of guns, which you need. But events that have occurred and imposed financial restrictions onto our country absorbed the entire budget, including the part that could be

disposed by our administration. Moreover, at present, the revolution which triumphs on the eastern portion of our island is creating a new obstacle in carrying out our aim; in fact, this portion, which was incorporated into the Republic I preside over, is in extreme poverty and thus justifies immense expenditures of our budget. If the circumstances, as we wish, improve again, then we shall honorably assist you, the sons of Hellas, to the best of our abilities.

Citizens! Convey to your co-patriots the warm wishes that the people of Haiti send on behalf of your liberation. The descendants of ancient Hellenes look forward, in the reawakening of their history, to trophies worthy of Salamis. May they prove to be like their ancestors and guided by the commands of Miltiades, and be able, in the fields of the new Marathon, to achieve the triumph of the holy affair that they have undertaken on behalf of their rights, religion and motherland. May it be, at last, through their wise decisions, that they will be commemorated by history as the heirs of the endurance and virtues of their ancestors.

In the 15th of January 1822 and the 19th year of Independence, BOYER

Sideris and Konsta provide the following analysis: Firstly, the letter addresses “citizens of Greece” who at the time were subjects of the Ottoman Empire. This demonstrates Boyer recognised their nationhood or peoplehood. As such, Greek historians regard this letter as one of the earliest acknowledgements of modern Greece. The significance of support from the progenitor of the earliest forms of democracy could also be considered a symbolic triumph for the Haitian Revolution’s legacy:

“It was precisely the difference between being a citizen and being a subject that was at the heart of the war between Greeks and Persians in the fifth century B.C., as well as at the heart of the revolutions at the turn of the nineteenth century C.E in the Caribbean islands or the Balkan Peninsula. For this reason, Greek historians consider this letter to be very important, as it was the first official recognition of the contemporary state of Greece and the first official reference to Greek citizenship. The recognition of the importance of this letter abounds in the Greek historical works, both in encyclopaedias and historical treatises” (Sideris & Konsta, ed., 2005).

Secondly, Boyer’s references to Greek classic history evoked the historical connections he believed both countries shared in their struggles against imperial rule: “All of them refer to the war that broke out during the fifth century B.C. when the Persian Empire attempted to conquer the democratic city-states in Greece. More specifically, they refer to a fight between the concept of democracy, emerging de novo at that time in Greece, and the despotism of a hereditary oppressive monarchy that at that time dominated the Persian Empire. Boyer refers to two well-chosen battle leaders of this war: Leonidas and Miltiades. He also refers to two historically important battles: Marathon, a beach about 42 kilometres northeast of Athens and of Salamis, an island just across the port from Athens. At the beach of Marathon, Miltiades, Commander-in-Chief of the Athenian Army, defeated the invading Persians (490 B.C.). (The long-distance race of Marathon commemorates this event). Leonidas, King of Sparta, died together with 300 of his fellow Spartans in their heroic but unsuccessful attempt to defend mainland Greece at the narrow pass of Thermopylae (480 B.C.). Finally, at the narrow straits of the island of Salamis, the Greeks won the final battle; under Admiral of the Fleet Themistocles a small fleet, manned by free citizens of Athens…”

Historians Franklin W. Knight and K. O Laurence explain in The general history of the Caribbean: The long nineteenth century transformations, that Boyer later offered 25,000 pounds of coffee to be sold for supplies, the importance of which cannot be understated [Knight & Laurence, eds., 1997:393]. Coffee was the third most valuable commodity in global trade by the end of the 19th century. It came to dominate both European and American consumption during a time of great expansion by both regions into Asia, Africa and Oceania (Topik, 2004).

It’s important to note however that Haiti’s intervention was not a major factor in Greece’s success in gaining independence. Great Britain’s intervention, which led to the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, probably packed a far greater punch as far as the Ottoman’s retreat goes. Regardless, Haiti’s role was crucial if not at least from an ideological standpoint. So much so that in 1935, Princess Marina of Greece visited Haiti to express gratitude for its role in Greece’s independence from the Turks.