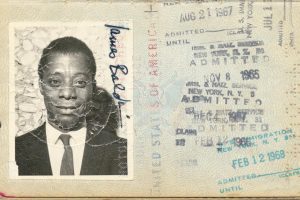

Siyah: The “Blaxit” Years of James Baldwin

This is the fifteenth instalment in ‘Siyah’, a series which explores African Diaspora and Turkish social and cultural narratives, with journalist Adama Juldeh Munu. Afropean look at celebrated African-American activist James Baldwin’s ten years spent living on and off in Istanbul at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Whenever people find out that I live and work in Istanbul, I often get asked two questions: “What made you work in Turkey?” and “What is it like as a Black woman here?” (i.e. do you face racism in Turkey?). These are questions I assume other Black creatives also face, at a time when increasing numbers of Black westerners are migrating from the countries of their birth to places in the Caribbean, Africa or other European countries, in a phenomenon known as‘Blaxit’. The term was coined in the wake of Brexit by academic, journalist, and human rights consultant Dr Ulysses Burley III. Commenting for The Salt Collective, he said, “America is on the verge of #Blaxit – a mass exodus of Black people. Where we will go I don’t know, but it’s clear that Black lives don’t matter here…”

The reasons for which people migrate vary, whether it is wanting a better quality of life, work opportunities, relationships, retirement or simply for adventure. Add to this the impact of racism, this may also include police brutality and the normalisation of far-right rhetoric in their respective countries, to name a few. It reminds me of the words of Emily Lordi for the New York Times, who remarks on the negro spiritual song ‘Steal Away’ as a fitting analogy for Black Americans who have ‘stolen’ themselves away from the United States as a response to being ‘stolen from Africa’ during the transatlantic slave trade.

‘Stealing away’ or ‘Blaxit’ are not new ideas for Black people seeking relief from racism. For instance, James Baldwin lived intermittently in Istanbul during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, having made a life for himself in Paris as a writer. Baldwin was one of the most accomplished writers of the 20th century, his repertoire traversing essays, novels, plays and poems. To do this, he broke literary ground in exploring racial and social issues – particularly his essays on the Black experience in the US amidst protests and sit-ins. His friend Zeynap Oral said that he remarked that “he couldn’t breathe” in the US, and could no longer work there. This was particularly triggered by the death of a friend who jumped off the George Washington Bridge.

In a feature for the New Yorker, in 1958, Claudia Roth Pierpont wrote that Baldwin meeting Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York was an important avenue for Baldwin to eventually migrate to Turkey. Initially, Cezzar was cast for a lead role based on Baldwin’s work Giovanni’s Room. While the play never made it to Broadway as Baldwin hoped, his liaisons with Cezzar would prove useful when he decided to visit the latter’s Taksim home in Istanbul, while working on a magazine assignment in Israel and Africa, in October 1961.

According to Magdalena Zaborowska, author of James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile, Cezzar and his wife Gulriz Sururi gave Baldwin a spare room in their apartment where he was able to work on his manuscript Another Country. The house no longer exists here like many of the places associated with Baldwin. Baldwin’s Another Country would be completed two months after his arrival.

Baldwin eventually moved out of Taksim into a “red wooden yalı, a waterside mansion, once owned by Ahmed Vefik Paşa, an Ottoman-era intellectual and statesman. He also spent some time at another multi-storied home on the Bosphorus strait located near the 15th-century stone fortress Rumeli Hisarı, from which Mehmet the Conqueror launched his attack on the Byzantines,” Suzy Hansen writes in Public Books magazine. “In those homes, Baldwin threw all-night parties and gave talks; he entertained Marlon Brando, Alex Haley, Beauford Delaney.”

Baldwin’s time in the city has left traces in his work, including his interactions with local culture and people, some of which were among some of his most important pieces because it reveals the comfort with which he could easily tie in race and sexuality. These include the essay collection No Name in the Street. Another example of this is the creator of the actor-protaganoist Leo Proudhammer in his novel ‘Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone and the conception of his last play ‘The Welcome Table.‘ He would also end up staging a play, Fortune and Men’s Eyes at the Istanbul Theatre which sadly no longer exists. As Hilal Isler recounts in James Baldwin Might Have Been Most Home in Istanbul: “Baldwin spoke of the positive ‘energy’ he felt in Turkey, and it’s been suggested this was a factor in his staying: because it was ‘easier to be gay in Istanbul than in America, easier to be black.’ Here, men could hold hands, and kiss one another in public, and maybe it meant they were gay, or maybe not. Here, people could be physically white-passing, but they weren’t considered white culturally or politically, at least not by the West. In this sense, Istanbul gave Baldwin the opportunity and space to re-examine the ways in which he had been thinking about race and sex. While he may have been fondly referred to as Arab Jimmy, his experiences in Turkey were sometimes fraught with the discrimination he escaped from in the US. While visiting a Turkish village, Baldwin was beaten by two men who used racial and anti-gay slurs against him, according to his biographer and friend, David Leeming.

But could he really escape the ‘Americanism’ of his identity and especially as a Black man? Baldwin was the subject of the film shot by late Turkish director Sedat Pakay, James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973), which was made towards the end of Baldwin’s stay in the city. It begins with a focus on Baldwin’s hands playing with Turkish prayer beads, tespih, linking him to a cultural practice that while foreign to him, speaks to a serenity that, as a Black American, had also become familiar given his time there.

In another shot, Baldwin then gets up from his bed sheets, walks to the window, looks out, and we can see over his shoulder a glimpse of the outside—an Istanbulite street view. Another scene shifts to him being in assorted public spaces as a visible Black man. We also hear his voice-over his thoughts on his voluntary exile from the US, how he felt that his freedom was paradoxically tied to American identity, that as a Black person was at this time still being hard-fought.

“I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am. But one can’t afford to worry about that … And […] perhaps only someone who is outside of the States realises that it’s impossible to get out. The American power follows one everywhere. […] One sees it better from a distance … from another place, from another country.”

Baldwin would live off and on in Istanbul for ten years, and once told his friend, the Turkish writer Yasar Kemal, “I feel free in Istanbul,” who replied, “That’s because you’re American.”