The Adventures of a Victorian Troublemaker: Henry Sylvester Williams

By Abena Clarke

His name* may have slipped through the annals of history but Henry Sylvester Williams was a man whose work back in the day is still echoing over a hundred years after his death. When considering the biographies of Sylvester Williams, WEB Du Bois, Marcus Garvey and Edward Wilmott Blyden, a group of final-year students at l’Université des Antilles et de la Guyane voted him the Father of Pan-Africanism. And why shouldn’t they? Henry Sylvester Williams coined the term Pan-African and organised the First Pan-African Conference in London in 1900, thereby sowing seeds that would yield extraordinary fruit half a century later, long after he’d been forgotten.

The conference was attended by eminent black activists from all over the world, as well as a number of the British political bigwigs of the day – Liberal Party people, Fabian Society folk, the Cobden girls – who believed social justice was for everybody. Assembled to organise for an end to colonial exploitation and racism, and for self-determination, their warm, formal reception by the British establishment – including a tea with prominent MPs on the terrace of the Houses of Parliament – is basically unthinkable to those agitating for such things today.

It’s a truth-is-stranger-than fiction type tale but essentially, once upon a time in Barbados (1867 to be exact), a baby boy was born whose family moved to Arouca in Trinidad and Tobago shortly afterwards. Henry Sylvester Williams would always identify himself as a Trini throughout his life. It’s possible he never actually knew he was born in Barbados. Non-coincidentally, Arouca is the same area in which another internationalist black activist would later be born. Once dubbed ‘the most famous black man in the world’ and a mentor of Kwame Nkrumah, while you might not have heard of Malcolm Nurse (his government name) George Padmore was a Somebody.

Young Henry Meets Ghanaian Royalty

When at boarding school in Port-of-Spain, Williams met a political refugee, who happened to be an African Prince from Ghana. Prince Kofi Intim was the son of overthrown King Kofi Karikari of Asante who had been forced to abdicate, and as fate would have it, was at school with the teenage Henry.

Prince Kofi had seen imperialism at work when he signed on his father’s behalf, with 19 other chiefs, the Treaty of Submission to the British at Cape Coast in Ghana in 1874. He shared his experiences, memories and thoughts, which, as he’d expected to become the 10th King of the Kingdom of Ashanti, may have been plentiful.

It’s hard to imagine that their conversations had no impact on Williams’ later politics, but I’m always up for a surprise. Arouca in the 1870s and 1880s was after all also home to a large population of transplanted Africans. As many had memories of their communities and lives in Africa, and many had lived through the transatlantic slave trade, Sylvester Williams’ environment perhaps enabled him to construct a full picture of late eighteenth century West Africa, the middle passage, enslavement, emancipation and ‘freedom’.

Growing up in a middle-class family in the British colony, his childhood would have been more comfortable than many of his Trinidadian peers, but born a descendant of enslaved Africans 30 years after emancipation but before meritocracy was idealised, meant opportunities were limited. Literally.

Ambitious Emigration: Establishing the African Association

Not one to shy away from a challenge, early on, however, Henry demonstrated drive, confidence and a passion for engaging with justice issues, particularly the injustices wrought by agents of colonialism. After a bout of teaching in Trinidad, and study in the US and Canada, Williams arrived in London in to pursue studies in Law at Kings College in the 1890s; seemingly just before the Law Society closed its doors to black members in 1894. He qualified and practised at Gray’s Inn.

Williams was nothing if not energetic. In his third adoptive country since leaving home, he continued undeterred: a rabble-rousing organiser on a mission to ensure that Victoria’s black subjects were conferred with the justice that British notions of fair play promised. The African Association was formed in September 1897, with an aim to:

“encourage a feeling of unity and to facilitate friendly intercourse among Africans in general; to promote and protect the interests of all subjects claiming African descent, wholly or in part, in British colonies and other places, especially in Africa, by circulating accurate information on all subjects affecting their rights and privileges as subjects of the British Empire, by direct appeals to the Imperial and local Governments.”

Bishop Alexander Walters was the first president. Henry Sylvester Williams was the secretary. In short, the African Association was concerned with raising awareness among the British public about the truth – i.e. the horrors – Africans in the British Empire suffered so that the government would be moved to fix them. Not wanting to put their public off from all the serious talk, other meetings and social events were held. The society was so successful in its self-set task that in 1898 Liberal party members encouraged the African Association to put forward MPs to forward their cause and advocate in parliament for people in the colonies. Keir Hardie, the Independent Labour Party’s first MP, would become a long-time friend to the organisation.

Naming Pan-Africanism: The First Pan-African Conference

After two years of Williams meeting people up and down the UK while lecturing on temperance, it was decided that a conference to bring together all the people concerned about the fate of black people should be organised by the African Association. Williams, with his extensive list of contacts in all corners of the Black Atlantic, was the principal organiser. He coined the term ‘Pan-African’ and delegates thereafter came to use it.

The First Pan-African Conference had 5 stated aims:

- To secure for Africans throughout the world true civil and political rights.

- To ameliorate the condition of our brothers on the continent of Africa, America and other parts of the world.

- To promote efforts to secure effective legislation and encourage our people in educational, industrial and commercial enterprise

- To foster the production of writing and statistics relating to our people everywhere

- To raise funds for forwarding these purposes

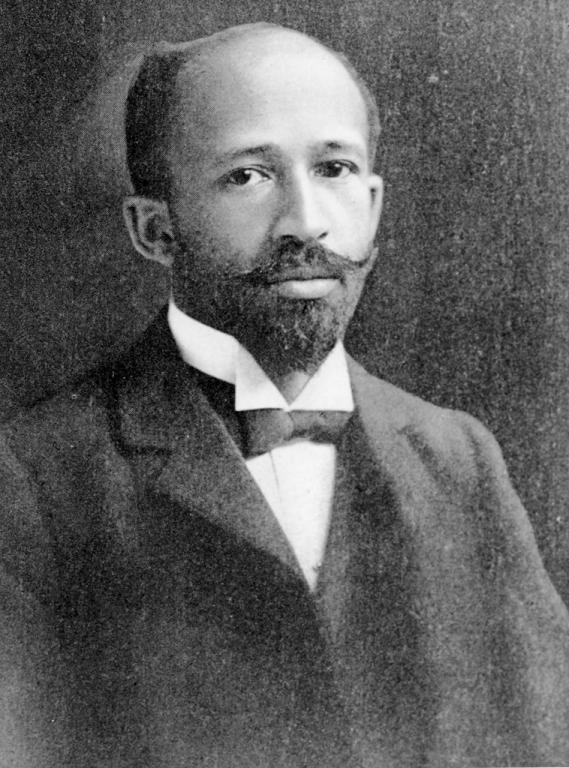

The First Pan-African Conference took place between Monday 23rd and Wednesday 25th July 1900. The American WEB Du Bois was among them and an important contributor to the debates at the landmark event in Westminster Town Hall. Alongside John Archer, John Alcindor, Anna J Cooper and Henry Francis Downing, many of the 40-odd delegates’ achievements have earned them a Wikipedia page a century later. Dr. Mandelle Creighton, Bishop of London held a tea party at Fulham Palace, his official residence, for the delegates. Samuel Coleridge Taylor, one of Britain’s most acclaimed composers at the time, provided the musical offering and later joined the committee. According to Du Bois however “the visit to the House of Parliament and tea on the Terrace was the crowning honour of the series. Great credit is due our genial secretary, Mr. H. Sylvester Williams, for these social functions.”

Serious Tings

This was not however just another, grander African Association social. Delegates of the First Pan-African Conference presented papers, shared experiences and put forward solutions. They addressed a number of issues including: discrimination, equal rights, self-government, perceived inferiority of black people, progress of the race, inadequate education, exploitation, to identify just a few.

According to Wikipedia: speakers over the three days addressed a variety of aspects of racial discrimination. Among the papers delivered were: ‘Conditions Favouring a High Standard of African Humanity’ (C. W. French of St. Kitts); ‘The Preservation of Racial Equality’ (Anna H. Jones, from Kansas); ‘The Necessary Concord to be Established between Native Races and European Colonists’ (Benito Sylvain, Haitian aide-de-camp to the Ethiopian emperor); ‘The Negro Problem in America’ (Anna J. Cooper, from Washington); ‘The Progress of our People’ (John E. Quinlan of St. Lucia) and ‘Africa, the Sphinx of History, in the Light of Unsolved Problems’ (D. E. Tobias from the USA). Other topics included Richard Phipps’ complaint of discrimination against black people in the Trinidadian civil service and an attack by William Meyer, a medical student at Edinburgh University, on pseudo-scientific racism. Discussions followed the presentation of the papers, and on the last day George James Christian, a law student from Dominica, led a discussion on the subject ‘Organized Plunder and Human Progress Have Made Our Race Their Battlefield’, saying that in the past “Africans had been kidnapped from their land, and in South Africa and Rhodesia slavery was being revived in the form of forced labour”. In South London-speak, we would describe the delegates as ‘not ramping’ – a strong way of saying they pulled no punches.

A Memorable Address

The Conference endorsed an Address to the nations of the world’. WEB Du Bois was chairman of the committee tasked with composing this document that was dispatched to leaders of countries with African subjects.

It was this text which first contained the line ‘the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line’ [sic], which would later be re-used by Du Bois in the foreword to his magnum opus The Souls of Black Folk. The address is worth reading in itself but I can’t decide whether in 2014 it makes for depressing or encouraging reading. It is such a simple request for the right to a full humanity that it could easily be made by any anti-racism organisation operating today.

The Address is clearly aimed at a white power structure, which it treats with reverence, though perhaps this was more a sign of the etiquette of Victorian England than impropriety. Of note is that in the intervening years between the first and fifth Pan-African Conferences, the hope for a change in attitude from that power structure had substantially diminished, assumedly in the face of constant evidence that this was Not Going To Happen.

Indeed, the main reason I consider this a hugely significant ‘Great, Black, British Moment’ in history is because it paved the way for the Fifth Pan African Conference, held in Manchester in 1945, at which representatives of almost all the soon-to-be independent African and Caribbean nations were present. Organised principally by Ras Makonnen, the aforementioned George Padmore, and Kwame Nkrumah under the auspices of the International African Service Bureau, change was now demanded rather than requested. And the change proposed in 1945 was full national sovereignty. At risk of sounding hyperbolical, it is difficult to over-estimate the significance of the impact of the Fifth Pan-African Conference on the decolonisation moment that began ten years later. CLR James would later remark that even the most ambitious anti-colonialists in 1945 could not have imagined the speed with which the colonial powers would relinquish the political power they’d enjoyed, for over a century, and in the Caribbean, for over three centuries.

On South Africa in 1900

As well as the Address, the First Pan-African Conference also outlined seven items that were then sent to the reigning monarch Queen Victoria, on the maltreatment of Black and Coloured people in South Africa for her immediate attention:

- The degrading and illegal compound system of native labour in vogue in Kimberley and Rhodesia

- The so-called indenture i.e. legalised bondage of native men, women and children to white colonists

- The system of compulsory labour on public works

- The ‘pass’ or docket system used for people of colour

- Local bylaws tending to segregate and degrade the natives – such as the curfew, the denial to the natives the use of the footpaths, and the use of separate public conveyance

- Difficulties in acquiring real property

- Difficulties in obtaining the franchise

The First Pan-African Conference thus specifically singled out South Africa as a problem 48 years before the election of the government that would pass the notorious apartheid legislation. The delegates may have foreseen the writing on the wall, but perhaps they also had too recent a memory of institutionalised enslavement to not speak out about a situation that appeared so identical.

The African Association was indeed effective in circulating information and fostering friendships across the diaspora: A certain John Tengo Javabu, an iconic figure in his own right in South African history would become one of Williams’ most trusted colleagues in years to come and joined the executive committee member of the Pan-African Association. Javabu founded and edited the first African-language newspaper in South Africa, Imvo Zabantsundu, and was involved in establishing the University of Fort Hare, whose alumni reads like a ‘who’s who’ of African anticolonial leaders with Mandela, Tambo, Pityana, Sobukwe, Nyere and Mugabe among many others. At the Conference, the African Association was transformed into the Pan-African Association. Henry Sylvester Williams began a period of extensive travel after the conference. He travelled to Jamaica, home to Trinidad and the US in 1901 to publicise the conference and establish branches.

This is where it gets really interesting.

On de Road: Jamaica and Trinidad

While still in England, Sylvester Williams had been corresponding with a certain Joseph Robert Love, who had arrived in Jamaica after spending 10 years in Haiti, and who Marcus Garvey would later name as a mentor. In the 1890s Love had set up a radical paper, The Advocate, and had organised the People’s Convention (not to be confused with Steve Biko’s Black People’s Convention), an organisation dedicated to changing the plight of Jamaica’s black poor. Dr. Love welcomed Williams and ensured his warm reception from the island’s like-minded folk. A Jamaican branch of the Pan-African Association was set up, to which the People’s Convention became affiliated.

When he went on to Trinidad, Sylvester Williams established several local branches of the Pan-African Association. One of his closest colleagues in Trinidad was James Hubert Alfonso Nurse. Mr Nurse headed the Arouca branch of the Pan-African Association, and in 1903 would father the boy who would become the renowned young communist and Pan-Africanist known as George Padmore.

After leaving the Caribbean, Sylvester Williams went on to the US. There he finally visited Booker T Washington’s Tuskegee Institute – he and Washington had corresponded for several years by this point. Although he did not attend the 1900 Conference, Washington had written to several black publications to encourage African-Americans to participate.

Into and Expelled from South Africa

In 1902 Henry Sylvester Williams completed his law studies in England and shortly after he left London for South Africa to ‘speak truth to power’. Being a black barrister in London at the turn of the twentieth century was not easy and Williams was constantly defending himself against spurious complaints from legal professionals. In South Africa, he was admitted to the bar, but opposed by ‘the legal fraternity’. Brotherly they were not apparently. He was nevertheless heralded as a hero for black and coloured South Africans. While working in the Eastern Cape and Cape Town he defended the grandson of the Basuto ruler Moshoeshoe. He later visited Basutoland and stayed with Chief Lerothodi, later saying ‘in those parts where no vestige of western civilisation had entered, [he] had enjoyed “the best hospitality and kindness from the people”.’

Henry Sylvester Williams appeared to leave a mark wherever he went. The African Political Organisation was established in late 1902 in Cape Town. Despite its name it agitated in favour of coloured not black South Africans. However historians have noted the striking similarity between the APO’s stated aims, and those of the First Pan-African Conference, and the wording of the APO’s Memo to Queen Victoria. The APO grew rapidly; in November 1902 it had 300 members in 5 branches, and two years later 2000 members in 33 branches. As well as Javabu, Williams was in contact with Sol Plaatje, a founding father of the ANC, and a number of other South Africans of note.

Perhaps he was too effective, because Williams was asked to leave South Africa as a result of his political agitating. Having left his wife and two children in England, he returned to them in 1905. Undeterred by his unofficial deportation, he continued his Afro-centric advocacy politics in England. Upon his return, he was elected to serve as a council for the St. Marylebone Borough in 1906 in the same election that saw John Archer first elected in Battersea.

Was it worth it?

Henry Sylvester Williams died in 1911 in Port of Spain aged only 44. He left behind a wife, Agnes Powell Williams, and five children. The family had been in Trinidad for a few years and Williams had set up a successful legal practice that had two offices at the time of his death. Between the relocation to Trinidad and Tobago and departure from England, Henry Sylvester Williams had managed one final trip; he accepted an invitation to visit Liberia extended by the President.

The Pan-African Association did not flourish, and its journal, The Pan-African was also short-lived. The resolutions and Address of the conference fell on deliberately deaf ears. The conference’s success lay in the articulation of its ambitions, in the networking it produced and the ideas it debated and enacted. At a time when the European and American intelligentsia was growing increasingly enamoured by eugenics, when pseudo-scientific racism was making strides, the counter-discourse of the early Pan-Africanists and the First Pan-African Conference would reverberate and influence generations of black thinkers around the world for well over a century.

WEB Du Bois and others tried to revive the ideal of Pan-African assembling after Sylvester Williams’ early death and a series of congresses were held between 1918 and 1929. But none had the prestige of the First Pan-African Conference, which had also been attended by non-Africans involved in anti-racist work, the suffrage movement and other social justice concerns.

In Their Own Words

The First Conference was also covered in the mainstream British press. Many people were astonished to find that Africans could articulate their own problems and conceive of possible solutions by simply working together. Only 15 years after another Conference in Berlin composed almost entirely of non-Africans had believed itself empowered to carve up Africa with a ruler, an assembly of African people asserted:

“Let the British nation, the first modern champion of Negro Freedom, hasten to crown the work of Wilberforce, and Clarkson, and Buxton, and Sharpe, Bishop Colenso, and Livingstone, and give, as soon as practicable, the rights of responsible government to the black colonies of Africa and the West Indies … Let the nations of the World respect the integrity and independence of the first Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, and the rest, and let the inhabitants of these States, the independent tribes of Africa, the Negroes of the West Indies and America, and the black subjects of all nations take courage, strive ceaselessly, and fight bravely, that they may prove to the world their incontestable right to be counted among the great brotherhood of mankind … If, by reason of carelessness, prejudice, greed and injustice, the black world is to be exploited and ravished and degraded, the results must be deplorable, if not fatal — not simply to them, but to the high ideals of justice, freedom and culture which a thousand years of Christian civilization have held before Europe.”

Friendship is a funny thing. Who could have predicted that the friendship of two boys in secondary school in Trinidad in the Caribbean, one a local boy from Arouca, one from the other side of the Atlantic ocean, the Gold Coast, would trigger a chain of events which would see their hopes manifested, in no small part through another friendship between a boy from Arouca and a boy from Cape Coast? 80 years after his father was deposed by the British, Prince Kofi Intim’s homeland Ghana would become the first colonised continental African country to become independent in 1957. Kwame Nkrumah, a strident self-described ‘Pan-Africanist’ and the former Gold Coast Colony’s first President would victoriously sign paperwork on behalf of Ghana, in the same room of Cape Coast Castle where Prince Kofi’s signature had cost him his kingdom. One of Nkrumah’s closest advisers was a certain George Padmore of Arouca, Trinidad, whose father was a close associate of Henry Sylvester Williams, principal organiser of the First Pan-African Conference held in Westminster Hall, London 23rd-25th July 1900. And school friend of one Prince Kofi Intim of the Asante.

*His name has not made historians’ attempts at recovery easy: For most of his life, he was known as Henry Sylvester Williams. But this was often hyphenated, and he also took up using the Frenchified spelling Sylvestre. So Sylvester-Williams, Sylvestre-Williams and Sylvestre Williams are all the same Henry Sylvester Williams used here.

I am trying to trace the family of my Grand Father Albert Duke Williams. Born in Port of Spain Trinidad and Tobago. My Grand Fathers mum was sister we believe to Dr Joseph pawan. I think he may have been a Grand son of Sylvester Henry Williams or a close relative. If their is anyone able to help me I would be most grateful. Thank you. Kind regards.

Good evening Shirley. Came across your post – not quite by chance, as someone messaged our daughter today to ask about Albert Duke Williams. The Pawan family is large and diverse with new discoveries being made through DNA links. Unfortunately we know nothing about the Williams family, but other members might. As far as we know, Joseph’s sister did marry, but to someone with the surname Roberts.