The ‘Black Fairy’ of Mannheim: Mabel Grammer’s Good Work in Post-War Germany

Written by Robert Fikes Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

It may be hard to imagine the deep reservoir of love and benevolence of a married couple who in 1955 welcomed into their home a half-German 9-year-old boy who was rejected by his guardians because he would likely die of leukemia within weeks. But this act of kindness was emblematic of Mabel and Oscar Grammer. Now 68 years later that boy is entombed with the Grammers in the historic Arlington National Cemetery. The private initiatives of Mabel Grammer in particular that radically improved the circumstances of 500 vulnerable kids, thereby attracting international attention, was more than an audacious rescue mission. Her crusade to place these innocents with loving families from Mannheim to Missouri also proved an opportunity for middle-class African Americans to demonstrate their willingness to respond to a humanitarian emergency far from their racially segregated communities.

The war that deposed Hitler in 1945 brought 1.6 million American troops to German soil, and over the next two decades an occupation force of several hundred thousand served mainly in Southern Germany (Bremen, Hesse, Bavarian, Baden-Württemberg). Military commanders routinely reminded their young subordinates to avoid fraternizing with local women but, in the grand tradition of every conquering army of the past, that advice was ignored. By 1955 nearly 68,000 children had been born to soldiers and their girlfriends in the Federal Republic of Germany, 4,800 of whom had fathers who were of African descent. Germans tagged the latter ‘mischlingskinder’ (a disparaging word for mixed-race or biracial children)while the black press in America popularized the non-judgmental term ‘brown babies’.

Enter Mabel Treadwell Grammer, a granddaughter of slaves, born in 1913 in Hot Springs, Arkansas, whose impoverished childhood was further marred by complications of peritonitis that nearly killed her and left scar tissue that prevented her from ever having children of her own. A graduate of Ohio State University, she married her second husband, career Army warrant officer Oscar George Grammer, in 1950 just prior to his deployment in Mannheim, Germany. A devout Roman Catholic, she soon visited Our Lady of Lourdes shrine in France where, according to a close relative, she was moved to rededicate her life to “help others instead of focusing on herself.” Upon her return to Mannheim, she was besieged by desperate young German mothers of children (some already in orphanages) whose fathers were African American.

The stigma of being the unwed mother of a child by a foreign soldier was problematic, as was the very presence of half-black children who, like the many bomb-damaged cities in the region, were an unwelcome visual reminder that the German nation had been invaded by foreign armies and suffered a crushing, humiliating defeat. These mothers knew well the sting of having their children spurned by fellow Germans on account of their colour and the bleak future likely in store for them. News reporter Douglass Hall described the children as “deserted, hungry, born amidst the ruins of Hitler’s Kingdom, hated because of [their] color, dirty for the lack of soap, diseased for the lack of medical attention.”

Fortunately, Grammer, who was a journalist and had high level experience in civil rights agitation in the United States (she had worked on such projects with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall) was uniquely equipped and predisposed to help. Her response to the pleas of struggling mothers and to the predicament of blameless at-risk kids was to establish her private adoption agency called Children Worldwide Organization, designed to cut through government red tape and bypass racially insensitive or hostile social service employees to allow speedy placement in homes both in Germany and the United States.

At the core of Grammer’s motivation was her certainty that blacks, whether in the U.S or stationed at military posts in Germany, had sufficient racial pride to compel them to intervene as best they could to improve the condition of an abused African-descended population abroad that they could readily identify with. Admittedly, that condition was brought about in part by their own young men, though it was also well known that many of them wanted to marry their beloved fräulein, legitimize their children, and return as a family to the U.S. – something roundly discouraged by German and, particularly, American custom and law during that era. Grammer also ascertained that German social welfare officials were of the opinion that the progeny of unmarried black-white unions would better profit from being placed in the home of persons of the father’s race.

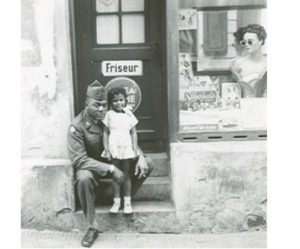

Using her professional connection with the weekly Baltimore Afro-American newspaper she bylined seven articles on the plight of Germany’s brown babies and her campaign to unite them with black families. Other leading American newspapers and magazines with majority black readerships endorsed her cause, among them the Pittsburg Courier, Kansas City Star, Chicago Defender, Ebony, and Jet. They encouraged sending care packages to German mothers whose addresses were sometimes listed in their pages; featured updated stories and announcements on the matter; and featured photos of irresistibly cute kids awaiting adoption and posing with newly acquired parents. At the same time, across the Atlantic, 35 volunteers of the Culture and Welfare Group of Mannheim, founded in 1948 by black military wives, responded by accelerating their delivery of food and clothing to the mothers of biracial offspring.

Grammer adeptly publicized her simple, step-by-step adoption guide which she titled ‘The Brown Baby Plan’. Researcher Yara-Colette Muniz de Faria explained how the plan and her partnership with the black press worked to great effect:

“While Grammer established contacts with mothers and children in Mannheim and wrote articles and made the administrative preparations for the adoptions in Germany, the Afro-American sought adoptive parents to match her reports by informing its readership about the black children in Germany. The paper functioned as Grammer’s contact address, often reporting on the front page of successfully arranged adoptions and the arrival of the children in the U.S.”

And Grammer wasn’t just a promoter of overseas adoption – between 1953 and 1961 she and her husband adopted 12 Afro-German children. She wondered: “I can’t understand why people think it is so strange for a colored couple to adopt these children. Don’t they think we have hearts, too? And you don’t have to be wealthy to adopt children. . . If you really want to do something you can.” When not advocating on behalf of prospective parents in German courts, visiting orphanages, listening to distressed mothers, interviewing potential parents in Mannheim, Karlsruhe, and Stuttgart, or drowned in paperwork, Grammer was devising supportive schemes like her negotiation with Scandinavian Airlines to fly adoptees to America at a discounted fare. Small wonder German newsmen took to referring to her somewhat affectionately as ‘The Black Fairy’, ‘The Brown Fairy’, and ‘Mommie Mabel’.

For her many efforts to find homes in American cities for 50 Afro-German children and hundreds more in the homes of African American military families in Germany, Mabel and Oscar Grammer received the Papal Humanitarian Award from Pope Paul VI in 1968, three years after the Grammer family relocated to a permanent residence in Washington, D.C. It must have been even more fulfilling and heartfelt to Mabel and Oscar that 10 of their 12 adopted children served in the military and 9 earned college degrees. Unsurprisingly one became a German language teacher.

One of their seven girls was named (or renamed) Mabel and one of the five boys was Oscar Grammer Jr. Their grateful youngest daughter, Nadja Yudith West (formerly Nadja Yudith Grammer), a West Point graduate, medical doctor, and from 2015 to 2019 the U.S. Army’s Surgeon General, once mused aloud: “To go from an orphan with an uncertain future to be a flag officer, general officer in the U.S. Army – it’s really hard to fathom.”

Oscar Grammer Sr. died in 1990 and Mabel Grammer died from hypertension and dementia at age 88 in 2002, leaving behind 16 grandchildren, 2 great-grandchildren, and an extraordinary legacy of uncommon altruism and the gratitude of innumerable beneficiaries of their compassion on two continents.

loved this article!!

Wow. Exemplary lives. Thank you for researching and writing.

I’m glad I found this. I was privileged to meet some of the Grammar children when they enrolled in Coolidge High School in Washington, D.C. and had wondered about their whereabouts.