African American Interest & Experiences in Russia: A Brief History

By Robert Fikes, Jr.

Robert Fikes, Jr., Librarian at San Diego State University, recounts the history of the African American presence in Russia from the 19th century, noting that African Americans have had a long and prominent history in the region, continuing to the present day, with a focus on the scholarly interest in the history and language by members of the African American intelligentsia.

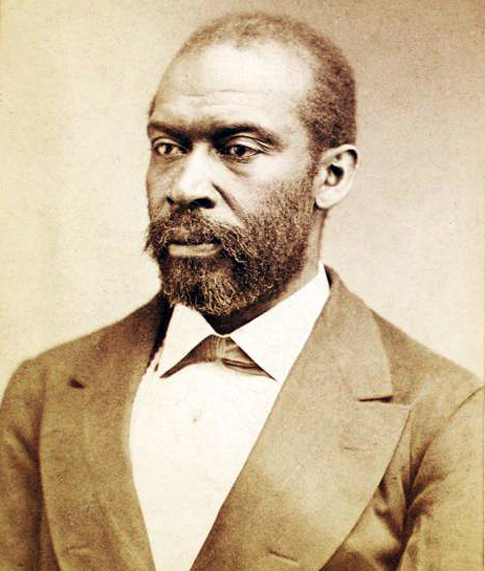

In early February 1869, Cassius M. Clay, the liberal American ambassador to Russia, was uncertain how Czar Alexander II would react to his personal request to have “a colored American citizen, presented to his Imperial Majesty, as there was not precedent.” He need not have worried however, as Civil War veteran and pioneering black journalist Capt. Thomas Morris Chester from Pennsylvania, was then asked to accompany the czar riding alongside the monarch and his staff in the annual grand review the Imperial Guard – stalwart men splendidly attired in tall black leather boots and gleaming gold and silver helmets crowned with a doubled-headed eagle – and following the awe-inspiring pageantry was treated to a fine meal at the dining table of the royal family. The educated and proudly erect son of an ex-slave, he gladly accepted the invitation and enjoyed an experience unparalleled for an African American in the 19th century. The black editors of the New Orleans Tribune thought the event significant enough that the ambassador’s dispatch to Washington concerning Capt. Chester’s gracious treatment in St. Petersburg was reprinted in the newspaper, believing it would be “instructive to the (racist) white population of the Southern States,” an example of how they should, in the ambassador’s words, “elevate the African race in America.”

Capt. Chester was not the only noteworthy African American to visit or reside in Russia, an unexpected reality that extends back to the late 1700s when black sailors were reported roaming the port cities of the empire. In 1824 Nancy Gardner Prince joined her husband who was a servant in the czar’s palace and recounted in a self-published book her nine-year stay there as a successful businesswoman and charity volunteer. Celebrated Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge made his first tour in Russia in 1858; future Artic explorer Matthew Henson learned to speak Russian while trapped in the ice-bound harbour of Murmansk in the early 1880s; the Fisk Jubilee Singers sang spirituals in Russia in 1896; and Harvard-trained diplomat Richard T. Greener served as the American commercial agent at Vladivostok at the turn of the century; while Mississippi native Frederick Bruce Thomas (a.k.a. Fyodor Fyodorovich Tomas) was a leading restaurateur and collaborated in building a grand entertainment complex in Moscow prior to the Russian Revolution.

Late 19th and early 20th century black visitors to Russia were a talented and enterprising lot who, though far away from home in a less known region of Europe, nonetheless felt acceptance there and appreciated their temporary and long-term stays in Russia, a faraway asylum from the unrelenting racism that awaited them back home. Eventually, the long acquaintance with Russia and the Soviet Union would result in a rather surprising scholarly interest in its people, history, and culture.

In the early 1900s of a number of African American professionals were in Russia’s teeming western cities. These were mostly entertainers in touring troupes, widely known as picaninny or coon shows, which profited from the vogue of black popular culture introduced to Europe and at its height from the turn of the century until the mid-1920s. In 1904 dancer Ida Forsyne began her nine-year stay in Europe using St. Petersburg as her home base, introducing the cakewalk and even adapting Cossack dance in her solo routine. A close friend who also spoke “perfect Russian” was actress-singer Laura Bowman who partnered with Pete Hampton performing in the troupe Darktown Entertainers which included Forsyne’s cousin Olga “Ollie” Bourgoyne; and Coretta Alfred, formerly of the Louisiana Amazon Guards, who studied at music conservatories in Moscow and Leningrad until reinventing herself as the actress and opera singer Coretti Arle-Tietz. Married to a Russian professor, Alfred died in Moscow in 1951. Both Burgoyne and songbird Abbie Mitchell, proprietor of a women’s apparel shop in the city that had 27 employees, were privileged to give command performances for the ill-fated Czar Nicholas II.

Other black groups and individuals who left an impression on Russian audiences in the period include the Fisk Jubilee Singers, in 1896; Pearl “The Mulatto Sharpshooter” Hobson, 1904 to circa 1916; the Creole Belles in 1905 with Georgette Harvey who took up residence in St. Petersburg when the troupe dissolved; the Black Troubadours, 1907; the Black Diamonds, 1912; Minnie Brown, 1915 to 1916; the Leland Drayton Revue, the first black jazz artists to enter the country in 1925; Sam Wooding and his Chocolate Kiddies, 1925; Benny Peyton’s Jazz Kings and the elegant male dance team of Rufus Greenlee and Thaddeus Drayton who hoofed for Stalin in 1926.

Arriving in 1904 were jockey Jimmy Winkfield who won the Moscow Derby, the Emperor’s Purse, and married a Russian baroness; and Robert Josias Morgan, the first black Eastern Orthodox priest. Though we cannot trace precisely when globetrotting business promoter-writer Henry F. Downing might have arrived, he possessed expert knowledge of the country as demonstrated in his play “The Shuttlecock; or Israel in Russia” (1913) with a cast of characters who personified upper class Russian society. And, as was the case with other African Americans, political instability compelled boxer Jack Johnson to curtail his stay in Moscow in 1914.

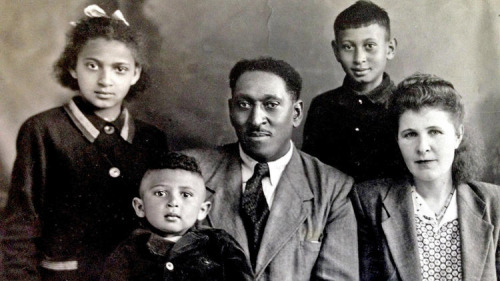

With the Bolshevik rebellion and World War I decided, African Americans departed for the nascent Soviet Union in two distinct groups: those attracted to and desiring to help fulfil communism’s promise of racial and social equality, and assorted artists and intellectuals lured by a welcoming totalitarian bureaucracy wanting to showcase its self-proclaimed accomplishment of anti-racism and international brotherhood in contrast to the United States. An early African American convert to communism was Brooklynite Otto Huiswoud, who in 1922 sailed to the Soviet Union to attend the Fourth Comintern. A trickle of visitors to the “worker’s paradise” in the 1920s grew substantially in those years leading up to World War II and included the left-leaning poet Claude McKay; agronomist George Tynes, writers Langston Hughes and Dorothy West; civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois; concert vocalists Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes; and a host of others fed up with American racism who chose to become permanent residents to live, work, fight, raise a family, and die there. Some lesser-known African Americans may have regretted their decision to emigrate there, among them factory worker Robert N. Robinson, whose presence was thoroughly exploited for propaganda value and who was prevented from returning to America; activist Lovett Fort-Whiteman, called “the reddest of the blacks,” a victim of the Great Purge who died in a Siberian gulag in 1939; and interior decorator Lloyd Patterson, mortally wounded in the German bombing of Moscow in 1941.

With the onset of the Cold War era and excesses of Stalinism exposed, African American attraction to communism waned dramatically. Confidence in the possibilities of a “Soviet miracle” was replaced with scepticism and revulsion. There remained, however, some evidence of continuing interest and curiosity in the culture and people of this enormous country. In the early 1950s there was an all-black Russian plaintext unit working inside the National Security Agency (NAS) that bolstered the career of James Pryde who became chief of a Soviet analysis section. In 1958 the government sent four Russian-speaking black guides to assist the American National Exposition in Moscow (among them Norris Garnett who later as a U.S. Embassy cultural attaché was expelled for allegedly inciting African students to actions “hostile to the USSR”); and novelist Ralph Ellison began teaching American and Russian literature at Bard College.

During the 1960s novelist-sculptor Barbara Chase-Riboud visited with dissident Russian artists; opera singer Simon Estes finished third at the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow; affected by the achievement of Sputnik mathematician Raymond L. Johnson and Charles V. Bush, the first black Air Force Academy graduate, learned Russian; television host Brian Gumble and symphony conductor Isaiah Jackson earned their degrees in Russian history at Bates College and Harvard University, respectively; poet Dudley Randall, who studied Russian at Wayne State University and had translated poems by Pushkin and Simonov, spent four months in the USSR; future astronaut Mae Jemison studied Russian throughout high school; and Barack Obama Sr. met the mother of the President in a Russian language class at the University of Hawaii.

During the 1960s novelist-sculptor Barbara Chase-Riboud visited with dissident Russian artists; opera singer Simon Estes finished third at the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow; affected by the achievement of Sputnik mathematician Raymond L. Johnson and Charles V. Bush, the first black Air Force Academy graduate, learned Russian; television host Brian Gumble and symphony conductor Isaiah Jackson earned their degrees in Russian history at Bates College and Harvard University, respectively; poet Dudley Randall, who studied Russian at Wayne State University and had translated poems by Pushkin and Simonov, spent four months in the USSR; future astronaut Mae Jemison studied Russian throughout high school; and Barack Obama Sr. met the mother of the President in a Russian language class at the University of Hawaii.

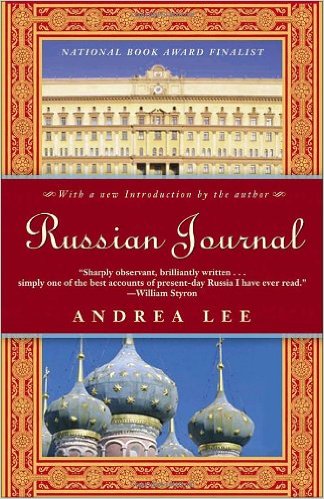

In the 1980s budding talk host and Navy Ensign Montel Williams mastered Russian at the Defense Language Institute; Gary Lee was the Washington Post’s bureau chief in Moscow; in 1989, John O. Killens published Great Black Russian: A Novel on the Life and Times of Alexander Pushkin; and in 1981 Andrea Lee published the highly acclaimed memoir Russian Journal. More recently, Ann Simmons was a reporter in Time magazine’s Moscow bureau; and diplomat Pamela L. Spratlen was posted in Moscow and Vladivostok before her appointment as U.S. Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan.

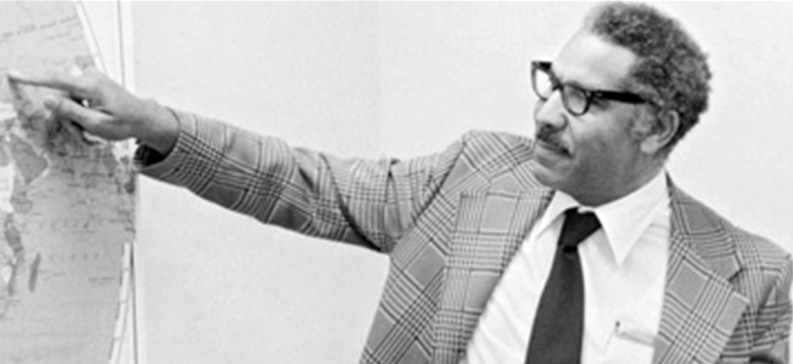

What has been least publicized about African American interest in Russia is the extent to which black scholars have studied and written on Russian life and culture. In the late 1950s Franklyn Jenifer, an alumnus and president of Howard University (a school that offers a Russian minor) learned Russian while working at the Library of Congress. In 1954, upon completing his thesis on Russian-Quaker interaction, Frederick P. Willerford graduated from the Columbia University Russian Institute. Six years later Allan B. Ballard Jr. wrote his dissertation at Harvard on the Soviet state farm system, followed in 1967 by linguist Herbert C. Miller who wrote on the fundamentals of Russian intonation at Pennsylvania State University. In 1971 Allison Blakely defended his dissertation on Russia’s Socialist Revolutionary Party at the University of California at Berkeley, and is best known today for his 1986 book Russia and the Negro: Blacks in Russian History and Thought, published by Howard University Press. Stephanie Scruggs’s Ph.D. in Russian linguistics was earned at Brown University in 1982.

Certainly over the past few decades the most visible black expert on Russia has been former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice whose book is entitled The Soviet Union and the Czechoslovakian Army (Princeton University Press, 1983). Other books are by professors Richard J. Payne, Opportunities and Dangers of Soviet-Cuban Expansion (SUNY Press, 1988); Susan M. Collins, Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the World Economy (IIE, 1991); Simone J. Alexander, who earned two university degrees in Russia, currently working to complete the book manuscript “Black Freedom in Communist Russia: Great Expectations, Utopian Visions”; and Sarah Valentine’s translation of selected poems of Gennady Aygi, Into the Snow (Wave Books, 2011). The new generation of black Russian specialists include historians Addis Mason (Ph.D., Stanford), Kimberly D. Adams at American Public University, and Cheri Wilson (ABD, University of Minnesota); language professors Raquel G. Greene at Grinnell College, Sasha Johnson-Coleman at Norfolk State University, and Kathleen J. Taylor at U.S. Military Academy; economist Lisa D. Cook at Michigan State University; and political scientist Natasha Bingham at Loyola University of New Orleans.

Certainly over the past few decades the most visible black expert on Russia has been former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice whose book is entitled The Soviet Union and the Czechoslovakian Army (Princeton University Press, 1983). Other books are by professors Richard J. Payne, Opportunities and Dangers of Soviet-Cuban Expansion (SUNY Press, 1988); Susan M. Collins, Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the World Economy (IIE, 1991); Simone J. Alexander, who earned two university degrees in Russia, currently working to complete the book manuscript “Black Freedom in Communist Russia: Great Expectations, Utopian Visions”; and Sarah Valentine’s translation of selected poems of Gennady Aygi, Into the Snow (Wave Books, 2011). The new generation of black Russian specialists include historians Addis Mason (Ph.D., Stanford), Kimberly D. Adams at American Public University, and Cheri Wilson (ABD, University of Minnesota); language professors Raquel G. Greene at Grinnell College, Sasha Johnson-Coleman at Norfolk State University, and Kathleen J. Taylor at U.S. Military Academy; economist Lisa D. Cook at Michigan State University; and political scientist Natasha Bingham at Loyola University of New Orleans.

Given the growing number of black students enrolling in Russian language classes and taking advantage of study abroad opportunities, polyglots like diplomat Terence Todman and Prof. Eugene Holman included Russian in their store of most useful languages, the State Department’s continuing sponsorship of black scholars and artists to Russia and its former Soviet republics (William Jelani Cobb, Jerry B. Daniels, Quintard Taylor, Rhodessa Jones, Terrell J. Starr, et al.) there is every indication that a broad-minded, well-educated segment of African Americans will retain and cultivate an interest, expertise, and muted passion for all things Russian.