Vienna to London: Black to Mixed-Race

I was born in Vienna, a place which has historically been a frontier between Eastern and Western Europe. I was primarily brought up in London, a city whose population reflects the reaches of the British Empire. It is also the place my parents forged new homes having left their respective homelands. My father is from Ghana and ethnically Asante (one should really say he is Asante first and foremost). My mother is a child of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire and my grandmother’s post-war exile from Sudetenland – her homeland. I’m mixed-race, even though the term never seems to capture the overlapping cultural and personal narratives that exist inside of myself and my family. As a child in the ‘90s, I went back and forth between being black in Vienna and mixed-race in London.

A film that conveys my times in Vienna, and interweaves the complex personal stories that reside in a society scared to embrace otherness is Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) by German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder. It’s a melodrama, a love story between an older German woman named Emmi (Brigitte Mira) and a younger black Moroccan man called Ali (El Hedi ben Salem).

Throughout the film we see Ali tread a landscape that keeps him at a distance both physically and emotionally. Fassbinder’s use of space in scenes is pivotal in showing how fragile people’s connections are. Characters group together through their isolation such as Ali and his Moroccan friends in the bar. They are also held together through their mutual distrust of foreigners, like Emmi’s neighbours who hold court on the staircase. These alliances show us how individuals seek self-preservation within a society that despises difference despite those who embrace it.

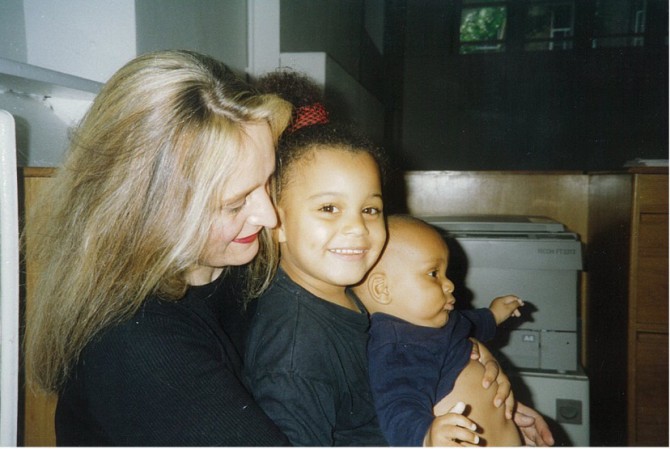

Emmi and Ali’s relationship connects us back to our human desire to be loved and the vulnerability that comes when one’s inner landscape is open to another’s. But love isn’t the panacea for the emotional devastation of racism. My grandmother, like Emmi, provided some refuge from the world outside. She encased my younger brothers and me in her flat when we would visit Vienna; it was a place of love, warmth, and family. Except this never was quite enough. Like Ali, our difference was felt and couldn’t be unseen. We still existed on the periphery.

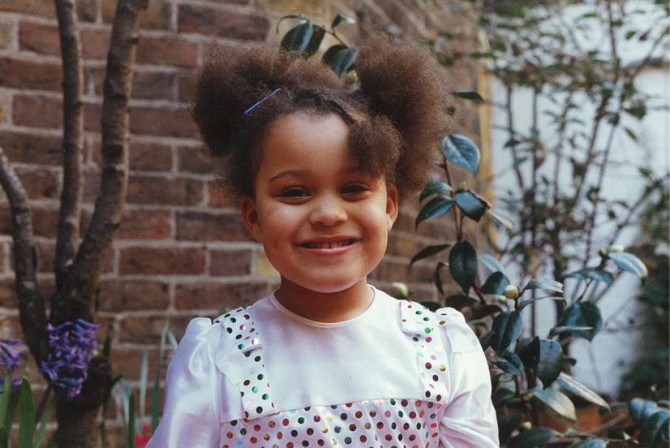

When spending my childhood Christmases in Austria, I would be greeted with the tradition of the Heilige Drei Könige. A group of four young carol singers would assemble and go door-to-door in their respective neighbourhoods; one dressed as the guiding star, the other three as wise men, except one in full black face. As a young girl I would anticipate their visit looking out the window to see them move further up the street and then to my grandmother’s front door. As I stood gazing upwards at them, I always wondered why one was painted the same colour as my father. The excuse of tradition didn’t explain the hurt of knowing my identity could become a costume.

In Fear Eats the Soul, a scene that encapsulates the destructive power of being ostracised is when Ali and Emmi are seated outside of a café. They are surrounded by rows of empty chairs and tables and an otherwise romantic scene becomes one of tragic honesty. Emmi finally admits Ali’s difference is intertwined in their relationship. The stillness that runs throughout the film doubles as a metaphor for the constant and suffocating awareness of being judged by strangers. As a group of by-standers gaze at them from a distance, Emmi breaks down and shifts between anger, despair, and then idealism. She believes that escaping briefly to somewhere, “where no one knows us and no one stares” will change their reality. The camera tracks slowly out into a wide shot as if to signify the dreamlike nature of her temporary solution.

Unlike Ali and Emmi, my escape was tangible and real. Back home in London, I was more attuned to the group of diverse friends and people I was surrounded by. In the midst of a less homogeneous society there was still the need for others to identify my difference, usually for their own comfort. Most assumptions placed me in the category of Afro-Caribbean and White-British, or sometimes strangers would play the dubious game of ‘guess the mix’. Mixed-race became a vague categorization, one steeped in a cultural heritage that did not belong to me, and tried to dictate the terms to which I could identify with my black experience.

As a child my father would tell me stories about my tribe, from the Anglo-Asante wars to Nana Yaa Asantewaa’s rebellion against the British. Colonialism had touched my family in different ways. My narrative is also embellished with their separation, losses, unity and defiance. My father’s pride and politics, coupled with my own need for self-identification, led me to seek out those who could discuss the complication of identity in its abundance and particularity. During my late teenage years I discovered writers like James Baldwin and Nella Larsen, who helped me recognise that power lay in the distinctness of my experiences. Their prose was remote from my life but intimately connected – I was understood.

Identity, like our relationships and environments, is constantly evolving. It’s a journey underpinned by our human desire to be acknowledged and know where we can place ourselves; it cannot be separated from our personal, family, and communal histories. Fear Eats the Soul shows us the fragility of human relationships when confronted with these questions. Ali’s fate is tied to a society where his obvious difference means he is always seen in opposition to it – he is a canvas for their ignorance. In my bid to interpret my own story and try to delineate between my lives in London and Vienna, I’ve found how those experiences coincide.

My understanding of difference and otherness were always in direct relation to the spaces I found myself in, it was never a question of how I identified myself but how others saw me. Now as a young woman, I recognise the importance of defining oneself on one’s own terms. As we exist in a broader European community that still struggles to let us convey the reach of our identities, whoever we may be, we have the right to assert our complex narratives. I exist partly in West Africa, Central Europe, and within a Black-Britishness that is still in the process of becoming. These unique connections are the hallmark of histories we’re all coming to terms with, in our own ways. I see my mixed-race as being rooted in the multiplicity of the African diaspora.

Beautifully written and great film reference. Still moves me to read experiences and feelings so close to mine, so close to many other afro-europeans. Thanks for sharing!