Flanders to Rwanda: ‘Going Back To Where I Came From’, then Returning Home Again

I come out of two different places. One I know all too well, the West of Flanders. It’s a place known for incomprehensible dialects, closely knit farming communities and conservative values. The other place I only knew from the news and the occasional anecdote by way of my mother. I am second generation Afropean. My father is born and bred Flemish but my mother is the product of a pretty horrendous colonial story: taken from her mother in the Rwandan countryside to be raised by the Belgian authorities in a ‘so-called’ orphanage created especially for métis children. This part of Belgium’s history has remained unrecognised by the mainstream and this is unlikely to change any time soon (however you can read Chika Unigwe to get a sense of how we deal with that past here).

You would think I would have gained some insight into the cultural identity package that comes with being ‘mixed’, but if there is one thing I noticed about how we perceive our identity it is that the differences between what my mother experienced and what I did outweigh our commonalities at every turn. For as long as I can remember I have seen myself as different to my general surroundings, engendering a sense of not belonging. This was not a negative feeling. I felt like I had an outsiders’ perspective whilst still being ‘in the loop’. Like having a secret extra bit of knowledge that allows me to bridge cultural divides and be approachable to people of different backgrounds or walks of life. Sometimes however the scales tip and the whole thing feels pretty much like being lost, however for me this usually coincides with a great musical or literary discovery, generally the best kind of solace available.

That same part that didn’t make sense back home did make sense there

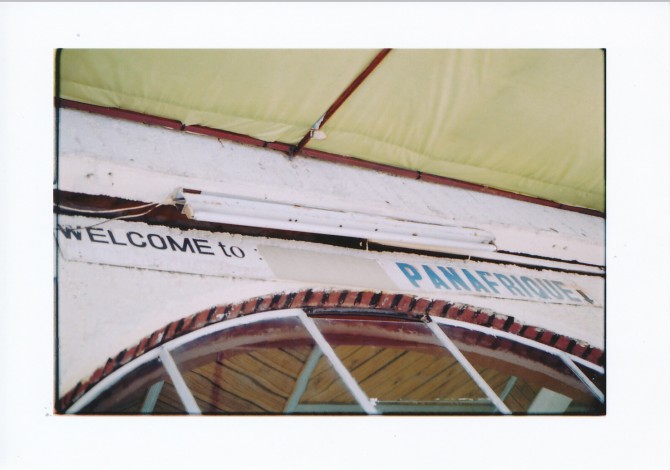

For some reason (which is pretty obvious come to think of it) I spend most of my time at university researching the Rwandan genocide and the impact that past still carries today. So, last year I decided to go to Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi for two months, alone. I couldn’t imagine that anyone would want to go with me and I also felt like I didn’t really want to share this experience. My family and my friends were happy for me and very encouraging, although sometimes I could catch a glint of “you are insane” in their eyes. I couldn’t (and I still can’t) blame them: because I was petrified. The day I left I almost fainted while going through customs. The moment I got on the plane and realised that everyone except me was really very black and very African I almost fainted again, and immediately felt like the biggest racist in the world. I wasn’t ready. I would be a huge failure and take the next flight back to my provincial, liberal and very white bubble of peace, love and middle class privilege.

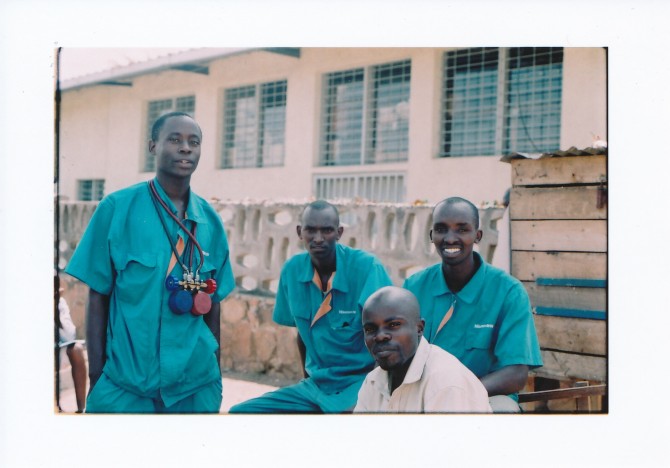

I cannot give a word for word account of everything that happened over the next few months but it was the best, hardest and most beautiful thing I ever did. It still feels like finishing a really good book where you wish you could read it again without already knowing what happens in the end. I didn’t see any exotic animals (except one hippo) but got lost in crazy East African cities, met and loved some beautiful people, ate a lot of meat and ugali, drank warm beer, found music that is so danceable it is still my standard soundtrack and I was hot for two months straight which is a big deal for most people from Western Europe. Most of all, I felt like a part of me belonged there – that same part that didn’t make sense back home did make sense there. That also implies that the part that does make sense in Belgium was pretty confused a lot of the time. When I went to meet my remaining family in the village my grandmother and my mother came from it felt almost transcendent, I was overcome by emotions I never thought capable of. It was one of the few times I wished I wasn’t alone. And I still haven’t decided if it was traumatic or great, but I know that in that moment I changed.

Identity is a tricky concept and it seems to me that a mixed identity is even more so. Sometimes everything falls perfectly into place, sometimes it seems like the parts can never fit and the thought that they might is just a fleeting illusion. When I came back I was living in that illusion and, as you can imagine, things fell apart fairly quickly after that. I had all the typical drawbacks from travelling alone a long time: harping on about the weather, missing interactions in the streets and going through a rollercoaster of highs and lows at any given hour of any given day. One thing however seemed permanently different – I had lost something along the way. My cherished privileged outsider’s perspective was gone and in its place came a general loss of connection. I couldn’t connect with my old European surroundings and I couldn’t connect with the African world inside Europe. I felt too white for some, too ‘other’ for others. My interests had changed dramatically going as far as my taste in clothing, music and even men. The Afropean inside me didn’t know which way to turn, how to unite this new person with my beloved home.

I once read that the best thing about travelling is coming back, in this case it seemed to be the exact opposite. I can tell you exactly when this changed: A while back I went to a concert in Brussels to see a Zimbabwean band. In the middle of the concert all the musicians abandoned their instruments and started singing in a beautiful harmony. Harmonies are without a doubt one of my most favourite things in the world. Music can transcend you but an acapella harmony, no matter what the music style is, amounts to the best music has to offer. In that moment I realised that there is much more to like or love about being Afropean than there is to hate. Although this sounds pretty corny it remains true, at least for me. From that moment on I decided to live by Chinua Achebe’s prophetic words: “Let every people bring their gifts to the great festival of the world’s cultural harvest and mankind will be all the richer for the variety and distinctiveness of the offerings.”

How much of who you are is defined by your racial ancestry? I was raised to believe we are all individual and special in our own right but this doesn’t ring completely true anymore. In my personal experience something makes you part of a community regardless of individual choice: the language you speak, the place you were born, your gender, your income or the colour of your skin. In this sense I feel very privileged for I was able to explore my mixed identity in a relatively safe and free environment. A lot of the issues mixed people deal with is race based, making the conversation racially tainted. As globalisation continues and people of different backgrounds continue to fall in love, more and more people like us will be born and the conversation will change. Our agency as a community is growing and with it our confidence. However, I went to that concert with a white friend of mine and the room was filled with white, black and mixed race people. People choose to enjoy a culture independent of their skin colour.

Something about being afropean is about being malleable thus not all the parts have to fit all the time. This can sometimes feel like a battle and it can just as often feel like an extra advantage, depending on the situation. But as the community grows I feel comforted by the idea that I have at least two places in the world that are a part of me and that I can ‘belong’ to both of them. This is what it means to be Afropean.

All text & photographs © Heleen Debeuckelaere

Twitter: @Hdbeucke

Loved this article and totally understand where you are coming from. I’m so happy to see you went back to your roots, being mixed raced is an amazing thing when you embrace both sides, it makes you feel whole