Appropriated Appellations, Cultural Fluidity, and Perpetual Dis-Location: An Interview with Andrew Moss

Written by Tola Ositelu

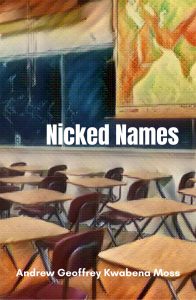

Writer, teacher and father-of-three, Andrew Geoffrey Kwabena Moss is even busier than usual. He’s hard on the publicity drive for his debut novella for young adults, Nicked Named. Loosely based on his own adolescence growing-up in monocultural Middle England, it follows the trials and tribulations of one Norman Smith; of mixed Ghanaian and English heritage. Targeted for being one of the few brown faces at school, he decides he’ll best the bullies through the power of the pen and with a little help from his friends.

Moss takes time out of the campaign trail to talk to Afropean about the genesis of Nicked Names, culturally liminal landscapes, being a lifelong knowledge-seeker and a veritable Global Citizen. He joins me remotely – very remotely – from his adopted home of Goulburn, Australia.

We take it back to the beginning and his parents’ unorthodox encounter. Moss seems to have inherited his facility with words from his Oxbridge-educated English teacher father.

“My dad was the first person from his working-class family who went on to University.”

Another point of pride for Andrew is the elder Moss’s chosen profession. He defied the low expectations of his own English teacher, William ‘Lord of the Flies’ Golding, who reckoned not with Moss Sr’s pedagogical aspirations.

Still, it wasn’t a straight trajectory. He’d initially considered the priesthood, before deciding to teach English in West Africa; first Nigeria and then Ghana. There he met Andrew’s mother, Comfort, who was also contemplating the religious life.

When Andrew was just a toddler in the late 1970s, concerns both macro-economic and familial saw the Mosses relocating from Ghana to the UK. Bedfordshire to be exact.

“It was very monocultural,” remembers Moss. “This was during the Thatcher era, of course. I could count everyone from an ethnic minority on the fingers of one hand. I was aware as a child that in people’s view, I was very dark-skinned, according to their colour spectrum. That would make sense to them when they saw me with my mum. Yet when I was with my dad, I picked up people second-guessing, looking uncomfortable. I was sensitive to their disappointment; like we were being judged in a sense. When I went to Ghana at the age of 17, I had the opposite experience. I was taken aback by how dark my mum’s relatives were. They looked at me and then looked at my dad and very quickly said, ‘You’re your father’s son’. People called me Obronni – white man – which is quite common. I started to realise how socially-constructed those perceptions are…”

Nicked Names showcases Andrew’s innate eloquence, with ample Parnassian flourishes and great word play (waggish chapter titles such as History Lessens, for instance). The novella is also strikingly personal and intimate. In one poignant passage, Norman notes ruefully…

“…It was tough, going through the motions, rehearsing and acting out a part that wasn’t really written for him, in front of an audience that frightened him. Time stood still…two torturing hands on a watch face that he couldn’t ignore…”

How much of Nicked Names is autobiographical?

“Certainly, the events are fictitious,” Andrew clarifies. “In Norman, there are aspects of myself as well as of my son. Blandford itself is a metaphor for monocultural market towns. It shares certain hallmarks of where I grew up.”

In another memorable scene, Norman takes a trip to a nearby multicultural town to have his hair styled. At the barber’s, he tries unsuccessfully to affect an ‘urban’ twang to blend in. Once again, it’s a scene lifted from the pages of Moss’ own life.

“Because hair is such a signifier of race and identification, that became important to me as I was growing up. I went to more cosmopolitan areas – Luton, for example – to get my hair cut. I was conscious – almost like double-consciousness – that I wasn’t part of that community. I wasn’t familiar with my African Diaspora heritage but I wanted to be. I felt I needed to explore that more, for my own sense of identity, well-being and pride. It was uncomfortable and that is something Norman goes through.”

As always, the concept of belonging itself can be something of a chimera…

“When I moved to London, I became more aware that your identifications were likelier to be through class,” Moss recounts. “You shared a language: Multicultural London English (MLE). I could see I was outside of that because of class. Not being from London made it harder for me to integrate with that culture. It’s something I’d wished I had grown up within.”

The novella’s protagonist has a very interethnic approach to overcoming racism. Norman enlists a close Italian friend, as well as East and South Asian classmates, to take on the racist bully through innovative rhymes rather than brute force. Is this Rainbow Alliance something Moss experienced in his formative years or rather does it speak to an ideal?

“More what I would have liked to see,” he admits. “Where I grew up, there were not many Chinese or Pakistani students. They were in Luton. You’d hear the racist chants. We had Pakistani-run corner shops and it was just everyday speech to talk about going to the ’P*ki shop’. I also got called ‘P*ki’. So [the novella’s Rainbow Alliance] was aspirational in that I heard [anti-Asian slurs] and I felt solidarity because I knew it wasn’t right.”

Andrew is a prolific poet, with a string of publication and performance credits. Nicked Names is his first major foray into long prose. How would he compare the process of working in each medium? Was prose a painful leap?

“Good question. What originally attracted me to poetry is quite pragmatic. I can write poems alongside my everyday life, whereas prose is more intense. Certainly, writing a novel is more intense as it involves a sustained thought experiment, where you inhabit that other world. When I was just starting out with poetry, I felt a great sense of achievement to produce something pretty self-contained, reasonably quickly. I like that experience of archiving, almost like a memorial. But then niggling away was the thought that I wanted to sustain a narrative. The novella was an opportunity to do that.”

Nicked Names is interdisciplinary; incorporating politics, history and even deep-cut obscure academic domains like sociolinguistics (which I happened to study for my Masters). Researched assiduously, much of it spawned from Moss’ own varied areas of personal interest. In passing he mentions the likes of Paul Gilroy, Du Bois and the mixed-heritage Chartist, William Cuffay – to name but a few.

“My history degree was a disappointment,” he explains. “Essentially, it was the wrong content; really dry, really colonial and not at all what I was interested in. I’ve always been fascinated by language. I grew up with this visceral knowledge that I’d spoken Twi to my grandmother. I felt I lost that language and with it, I’d lost particular cultural perceptions that are being reflected or activated through certain languages. I’m intrigued by the intersection between language and other cultures. And that’s a theme in the book… X stands for Y. The low-cost signals, the symbolism of language. Looking at Norman’s hairstyle and the semiotics in that. Also, how you can re-appropriate language. An obvious example is ‘n**ga’ being re-appropriated and having a community of people who trust that it has a different connotation…”

If there’s one serious gripe with Nicked Names, it’s how much female characters are sidelined, especially Norman’s mother. Whilst Mr. Smith is prominent, the matriarch is notable by her absence. It appears to reflect an unconscious tendency of some (otherwise socially-conscious) black men to overlook the perspectives of Afro-descendant women. Moss’ rationale for the apparent oversight is hardly illuminating:

“I’m not looking at it in terms of ‘Oh, I need to represent male and female in a clinical way’. To me, there’s so much that would be already influencing Norman through his mum and through his awareness of his Ghanaian culture, I guess. That’s already present and that is the backstory.”

Yet this doesn’t explain why Norman’s father – already part of the dominant culture – is given a distinct voice, whilst Mrs Smith remains a shadowy figure.

Moving on to a more positive feature of the novella, Norman expresses admirable views on the cultural significance of African nomenclature. He resents that he doesn’t have a Ghanaian forename; something he’d wear ‘as a badge of honour’ in his mostly Anglo-Saxon environment. Names are political, after all. Historically, European settlers and expats rarely ever felt the need to give their children local names to help them ‘assimilate’ with the colonised population.

Norman appears to be a mouthpiece for the author’s youthful ideals, which he’s found harder to follow through as an adult. Whilst his three children all have Akan day-names, these are not what they are known by.

“I’ve fallen into the same paradigm that I wanted to rebel against. “It is a pragmatic approach. Now I can identify with some of my parents’ decisions,” Andrew confesses. “I take your points as well. All the more reason, living in a predominantly Western society to go one step further and have [an indigenous name] as your first name. I was negotiating that with the mothers of my children. Ultimately, they are going to school in Australia, quite a monoculture…. My children are all very proud of their Akan day-names and they know the system behind it.”

Andrew acknowledges that his children are growing up in spaces where African communities are scarce, if present at all. He’s endeavouring to pass on the cultural baton in other ways.

“My children all have a copy of the book. I have a lot of conversations with them about my experiences of growing up and my interest in other cultures. They’re very proud of their Ghanaian heritage as well. I hope they have a more rounded sense of what you can learn from your own family history and how that connects with Diaspora.”

As a teacher, how has Moss’ experience being educated within a colonial system impacted his teaching style? Does he try to redress the errors of the past (and present)?

“I think my mere presence – being part of a Western education system and being someone from a minority – is powerful in itself,” he posits. “I hope I bring connections from my own personal narrative; a tolerance and an awareness that there are whole bodies of knowledge that are not represented within the Eurocentric curriculum. For example, in the Australian context, now they learn about colonisation, the White Invasion and the significance of indigenous history. I want to link that to other colonial experiences and to my own history. I suppose you’d call it an auto-ethnographic approach that informs how I teach.”

Moss spent two and a half years teaching English in the Chiba Prefecture, Japan before heading South to the Antipodes. How would he describe his experiences of ‘blackness’ in these spaces?

“In a sense, Blackness in Japan is very confusing. There’s an appropriation of Hip-Hop culture on the surface. Some of it is generational as well, from what I could glean. There are all sorts of interpretations that go on. I don’t know how much racism there was. I was Gaijin predominantly; just another foreigner,” he explains.

“I know politically that there is a history of more tolerance for the white European’ Andrew continues, ‘I don’t know if there’s also an exoticism to the interest I could see in Black American culture, in particular, but there seemed to be more tolerance than I was led to believe.”

What about the former settler colony, Australia – Andrew’s home for the past 14 years?

“I now live in a place called Goulburn. It still has that frontier mentality. You can sense that trauma of the convict history but also the treatment of indigenous people. You will not see ‘Burbong’ – the Aboriginal name for the town – anywhere. There’s literally been historical erasure,” Moss reflects.

“There were Black Africans on the first fleet [from the UK]. That’s a history that is very much marginalised. I’m certainly in an area that is very Anglo, very traditional. In more urban settings, there’s an absolute contrast. The cultural shift [between cities] is significant. Regional Australia and Urban Australia are very different, regional being much more conservative-minded”

“Certainly, Australia hasn’t come anywhere near to terms with its colonial past,” Andrew laments. “They had the Kevin Rudd apology but you also had the Cronulla riots. There’s a real tension and a gulf between people who are very politically aware of the history and the bumper stickers: ‘F*** off, we’re full!’ The irony of that in a country that is so sparsely populated. It’s just incredible. I’ve been called all kinds of names…”

Has Andrew noticed any differences in his own behaviour living on the other side of the world?

“There’s an abrasive quality about slang and language here,” Moss observes. “At first, I found it – and still find it – hard to negotiate. There’s that rebellious approach that people pride themselves on here. With that is a certain directness, with abbreviations like ‘Leb’ for Lebanese or ‘Abo’ for Aboriginal. ‘Wog’ was used for Greek and people of Mediterranean heritage. When I first arrived, I was really shocked by how blatantly racist terms were casually bandied around. The longer I’ve been here, I’ve started to challenge that more.”

Andrew’s experience as an outsider in both cultures would be familiar to many in the African Diaspora. Is there a definition of Afropean with which Andrew Geoffrey Kwabena Moss is at ease?

“Anglo-Ghanaian is in my bio. I’m happy with that identification. I feel it describes my background,” he asserts. “I think it’s important that people recognise that the ‘Anglo’ is important but I’m also proud of my Ghanaian heritage. I’m finding out more about it. I’m interested in some of the theories about the interplay between Egyptian and Akan cultures, for instance. I’d probably at some stage like to go back to Ghana. There are more questions I have to explore. It would be quite uncomfortable and challenging but I feel I need to do that.”

Moss returns to the slipperiness of belonging.

“My friend, Dr Marva McClean [author of From the Middle Passage to Black Lives Matter, Ancestral Writing as a Pedagogy of Hope], has reconciled to never finding home in a geographical place. That’s not an uncommon thing. I look at it now as gaining homes, as I continue to move around. I am also being dislocated at the same time, so there’s a pain and pleasure in it. The ambivalence is true to my experiences growing up. Being uncomfortable is my default, in a way.”

A longer, two–part version of this interview appears on the I Was Just Thinking… blog.

Andrew Moss online