Colourism, Passing, and the Bizarre Circus of Black Racial Imposters in 1950s America: Part One

“There ain’t a white man in this room that would change places with me. None of you. None of you would change places with me, and I’m rich!”—Chris Rock, comedian

It really wasn’t so long ago in the United States when its African-descendant citizens could hardly have conceived of or uttered such bold, self-affirming phrases as ‘Black is beautiful,’ ‘We shall overcome,’ or ‘Black Lives Matter.’ This shouldn’t be the least bit surprising when one considers that racial segregation, brutal discrimination, and routine slights and regular humiliations were the order of the day (and in many instances, sadly still are). During the 1950s, the era on which this essay focuses, the civil rights revolution was in its infancy. Blacks were systematically denied opportunities and benefits ordinary white citizens took for granted as rightfully theirs.

They had grandparents and great-grandparents born into slavery living amongst them, to remind them of how far they had progressed. Still, they could not point with pride to a Black mayor of any major city, a 4-star general, a manager of a major league sports team, a U.S. senator or state’s governor, a Fortune 500 CEO, an airline pilot, a Miss America, a TV news anchor, and so on. And there was no pre-eminently powerful Black figure to exalt and inspire them; certainly no- one resembling a Barack Obama in their midst. Confronted with a functional pigmentocracy predicated on the ‘one drop (of African blood) rule’ within and outside the Black community, and faced with fewer life options, masters of artifice found ways to bend adverse circumstances to their advantage.

“I nearly died of terror the whole nine months before Margery was born for fear that she might be dark. Thank goodness, she turned out all right.”—Nella Larsen, Passing

The Ironies of Colourism

Psychologists characterise the normal reaction to extreme danger and stressful situations well beyond one’s control as a fight-or-flight response. Often also attendant is self-loathing and the kind of desperation that compels people-in this case, Black-to go to extraordinary lengths to be respected and valued by others, even if this means mimicking the standards and habits of their white oppressors. For centuries African-Americans schemed to make themselves less hated, pitied, and disdained; not only by whites but by fellow Black folk as well. Endless examples of such behaviour are on display in the pages of the two most successful Black-oriented periodicals founded in the post-World War II era: Johnson Publishing Company’s monthly Ebony and weekly Jet magazines.

Of the two magazines, Ebony – modelled after the wildly popular white-oriented Life magazine, filled with in-depth feature articles and numerous photographs – was preferred by aspiring members of the Black middle and upper classes. It was something that could be tastefully displayed on the living room coffee table. Jet, on the other hand, nearly pocket-size with half as many glossy pages per issue, replete with easily digested single-paragraph stories that were often salacious, gossipy or gruesome, was tailored for a less discerning audience with a shorter attention span.

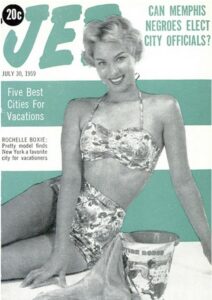

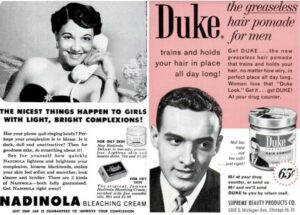

Launched in 1951, the most striking thing about Jet was its exploitation of fit young female models in swimsuits, usually four or five per issue and, most noticeably, none of whom in the 1950s were dark-skinned. There were sections on politics, religion, crime, sports, foreign affairs, entertainment and more but a light-skinned model was used on the cover of most issues to sell the magazine. Looking back from a comfortable vantage point in 2023, had these cover models and other provocatively dressed women (and the use of some light-skinned Black men) in the advertisements of both magazines been used just occasionally, it would not have attracted attention. However, the frequent showcasing of such models over an entire decade suggests something deeply disturbing: that after centuries of being told Black physical traits-in particular darker skin tone-were inherently less attractive, even repulsive, Black people themselves had internalised this. By the mid-twentieth century the overwhelming majority subscribed to the Caucasian/Nordic ideal of beauty, this being also associated with intelligence, authority, privilege, and greater access to any desirable thing.

At least every other issue of Jet had one or more stories about interracial romances and marriages happening across the nation and abroad. Taking into account the subordinate status of most of the Black population, then the not very subtle message conveyed was that the ultimate solution to the “race problem” was assimilation, amalgamation, or interracial marriage. If that couldn’t be done, soon enough the quicker alternative was to purchase heavily advertised whitening creams and lotions, and straighten those ‘stubborn’ naps with thick grease and hair relaxers. The ultimate aim was to look and feel more respectable; like white folk were perceived.

“I am an invisible man. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fibre and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” — Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Passing in Plain Sight

Maybe sometime in the near future there will be a statistical report of how many Caucasians have done a genetic test to reveal the full extent of their European roots, only to find – to their utter dismay – something totally unexpected lurking in the family tree.

Light-complexioned African-Americans with enough European heritage could and did seamlessly slip into the white world. It has been estimated that by 1950, eighty-seven years after the Emancipation Proclamation, no less than several hundred thousand – and upward of several million persons of African descent – had crossed over into unsuspecting white America. This was called “passing.” Some moved away from home, cut ties with family and friends, and never looked back. Some were part-time passers who spent the day pretending to be white but spent the night with the darker-skinned people they loved and had grown up with.

Less attention has been given to a third category: casual passers who did not actively deceive people about their racial background but instead, allowed everyone to presume whatever, while they navigated interacting with all races. A perfect example was Cynthia Hudgins in Coronado, California. Her mother was Scottish and her father passed for white. Her emotionally distant parents showed little affection for her, leaving her ex-slave grandparents to raise her. In her memoir, The Other Side of the Fence, Hudgins recounted how she spent most of her life in extreme fear of being outed as Black, and tormented by guilt for permitting people to think she was pristinely white.

Another case involving casual passers – albeit without as much psychological trauma – was that of drama students, Gabrielle Bradby and Pauline Green as well as Ebony Fashion Fair model and Jet covergirl, Rochelle Boxie (see Jet photo above). The three young ladies were considered viable prospects for the lead role in the proposed movie I Passed for White, based on a book about the true life story of a woman who hid her Black ancestry from her white husband until their fragile marriage ended in divorce. The film’s director aimed for realism in searching for the right actress. He complained that he had heard of “several (light-skinned actresses) who won’t even come to me because they are actually passing for white in real life.”

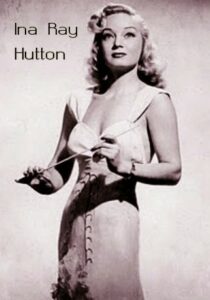

Perhaps one of those passers was star of stage and screen Carol Channing. She was late to admit her grandmother was Black and her father was Afro-German. Similarly, Ina Ray Hutton, alternately designated as “Negro” and “mulatta” in the U.S. Census, left behind her Black Chicago neighbourhood to lead an all-female band and briefly starred in her own television show in the early 1950s on KTLA, Los Angeles.

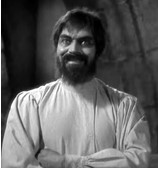

Jamaican-born character actor Frank Silvera (featured image, above), no stranger to the Black press, was steadily employed in Hollywood and on Broadway largely because it was impossible to racially classify him. He could thus be seen by 1950s movie audiences in the role of a Mexican, Native American, East Indian, Italian, or Polynesian. Having earlier performed in Othello and Emperor Jones, in 1962 he founded the Theatre of Being in Los Angeles to mentor Black actors.

A contemporary, Noble Johnson, fashioned a long career in motion pictures that closely mirrored that of Silvera’s. Though a shade darker, he played practically everyone: Arabs, Chinese, Nubian, Indian, Mexican, a Jewish man, but most often a Native American- an ethnicity for which he was typecast. Also like Silvera, Johnson never concealed the fact that he was Black or part Black. To the contrary, they both profited from being of mixed heritage.

Not to be left off the list of standout passers in plain sight, was New York literary critic Anatole Broyard. He was known to fly into a rage when someone alluded to his Blackness; something of which both his black and white acquaintances were well aware but were careful to only talk about in whispers when he was not present.

One of the saddest stories of passers was that of Philippa Duke Schuyler, a once widely publicised musical wunderkind and daughter of a far-right Black writer of some note and an overbearing white mother. In 1959 she reinvented herself as a Spanish pianist named Felipa Monterro y Schuyler so as to be judged solely on her ability as a masterful pianist, touring in Europe and lecturing in the U.S. In her mind, this would avoid the stigma of being labelled a “Black pianist”. At age 35, she aborted a child that resulted from an affair with an African diplomat, wanting instead a future with a white husband who would give her a child with “ideal” white features. Her unnecessary machinations eventually unravelled. Nevertheless, before her untimely death, during her later career as a roving journalist, she seemed to develop at least a modicum of respect for Black people and the civil rights movement and was disturbed by racism.