Domenico Mondelli: The Rise, Fall, and Restoration of a Black Italian Hero

Robert Fikes Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

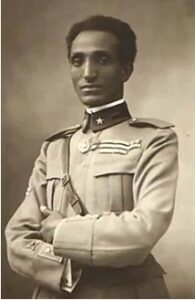

Standing dead centre in a photo surrounded by a score of fellow officers, with more shiny medals on his chest than anyone, is Domenico Mondelli, the only dark-faced man in the group. Owing to the recent work of a dogged researcher, librarians, and cooperative relatives who finally pieced together many more details about his astonishing life, we now know how he avoided death in Africa as a child to become the world’s first Black aircraft pilot; won distinction in both the Italian Army and Air Force; defied Mussolini’s fascists to eventually become the highest-ranking Black soldier in his nation’s history; and ultimately was celebrated for his singular accomplishments.

Ascent of the ‘Black Eagle’

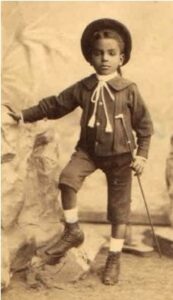

There are two plausible competing stories about how Mondelli, believed to have been born June 30, 1886, wound up in a foreign city 2,600 miles from his birthplace. Italy joined other European countries in the late nineteenth century mad ‘scramble for Africa’, first colonizing Eritrea prior to extending its imperialist tentacles into other regions on the Horn of Africa. One version has it that one day in 1890 while traveling between Debaroa and Asmara, career army officer Attilio Mondelli came upon an abandoned 4-year-old boy in extremely poor health named Wolde Selassie, felt pity for the child and decided to adopt him. The other version claims that the lad had not been ‘found’ but was in truth the officer’s natural son, the product of a liaison with an Eritrean woman, and that Attilio confessed his paternity on his deathbed. In any event, the boy was given the Christian name Domenico for he was said to have been rescued on a Sunday. Shipped off to the city of Parma in northern Italy in 1891, he had the good fortune to be raised with Attilio’s two illegitimate daughters in an upper-class household that welcomed him.

Unsurprisingly, Mondelli followed the family tradition and was set on the path for a career in the military starting with his entrance first at the Scuola Militare di Roma (Military School of Rome) in Palazzo Salviati in October 1900, then the Reale Accademia Militare di Fanteria e Cavalleria (Royal Military Academy of Infantry and Cavalry) in Modena, where he graduated in 1905 as an outstanding cadet leader with the rank of Second Lieutenant. Well prepared, he took command of a succession of elite Bersaglieri (sharpshooting attack troops) until the outbreak of World War I.

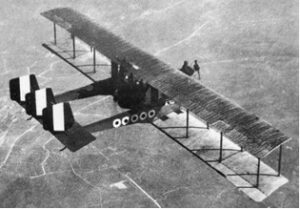

He never explained what attracted his interest in aviation, whether it was its technical aspects or simply the exhilaration of soaring high above land, but his application to join Italy’s fledging Italian Air Force resulted in training that made Mondelli the world’s first Black military airplane pilot. It had long been assumed that either Turkey’s Ahmet Ali Celikten or the American Eugene Bullard deserved such recognition, but it has been established that Mondelli began formal flight training earlier than these pilots and was awarded his flight certification from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale on February 20, 1914, almost two years ahead of them.

As squadron commander he flew numerous reconnaissance missions over enemy (Austro-Hungarian) territory, oftentimes through mountainous terrain and at other times at low altitudes to get a better look from an open cockpit which presented its own hazards. Adroit in locating artillery positions, on a bad weather mission in 1915, flying low close to the border town of Alto Isonzo his plane was hit by shrapnel but somehow he managed to land without crashing. For ‘showing calm and courage’ and ‘contempt for danger’, Mondelli was awarded the Bronze Medal for Military Valour. He next switched to large bombers that struck targets as far away as Slovenia.

The days of the ‘Knight of the Air’ as a bomber squadron commander came to an abrupt halt in 1917 when his wings were clipped and he was reassigned to the Bersaglieri. Some have speculated that Mondelli, who had a reputation for womanising, may have had an affair with a superior officer’s wife, or that he may have accidentally bombed some Italian soldiers. Regardless, he proved equally proficient leading ground forces – destroying machine gun nests, taking prisoners, and inspiring his fighters to perform extraordinary feats. Late in the war a military observer reporting on the frontlines wrote:

“On our right, the wonderful negro (sic) has broken through the enemy lines. He is one of our most beloved officers. . . the black Abyssinian, thin, curly-haired, with white teeth and perfect Italian speech; he hates bureaucracy and loves the Bersaglieri.”

Mondelli earned two additional bronze medals and two silver medals, but at a cost: twice blasted in the face with grenade fragments that permanently damaged his right eye that worsened as he aged.

Though greatly respected by subordinates who risked their lives with him in battle, Mondelli was considered a bit of a prig. He was fastidious to the point of foppishness, and went strictly by the rule book. There were three other Afro-Italian officers who fought in Europe during the war who attracted little attention. Not only did Mondelli far outshine them on the battlefield but at the start of the post-war period he had the advantage of useful social connections since he was a Freemason.

The Downfall

A lieutenant colonel in 1922 who wholly expected to be promoted to full Colonel, Mondelli could not have foreseen the ebbing of his military career. Until then he had not experienced significant discrimination on account of his race, class status, or membership in a secret order. Everything changed that year when Liberal Italy overnight became Fascist Italy with a posturing caricature of a dictator named Benito Mussolini installed as head of state, accompanied by the virulent racists Roberto Farinacci and Giovanni Preziosi. A year earlier ‘Il Duce’ told an audience in Bologna: “Fascism was born… out of a profound, perennial need of this our Aryan race.” Long before Mussolini’s association with Adolf Hitler and collaboration with anti-Semites, he professed belief in eugenics and the cultural superiority of Italy that formed the basis of his movement’s perverted nationalism, the supposed sure answer to the growing threat of ‘blacks and yellows’ and communism.

Proud, patriotic, steeped in a military tradition, and unfailingly respectful of authority, Mondelli was politically right-leaning except for, of course, the right’s flirtation with and toleration of racism. In fact, in the early 1920s he joined the Voluntary Militia for National Security (infamously known then as Blackshirts), a haven for job seekers that required him to swear allegiance to both King Victor Emmanuel III and Mussolini. However, his enlistment may well have been in part a self-serving stratagem to ensure his promotion and future ambitions in the military. If so, that stratagem failed miserably. The new regime not only disdained ethnic diversity, it also waged war against Freemasonry, fearing its members owed more loyalty to fellow Masons than to the Fascist state. A law enacted in 1925 forbade government employment of Masons, essentially ending Mondelli’s active military career, forcing him to leave the order and begin inactive reserve military service. As one writer bluntly put it: “. . . the fascist regime didn’t want him or the three other Black officers to wear a uniform.”

If the Fascist hierarchy imagined Mondelli, one of the most decorated officers in the Italian army, would henceforth wander in the wilderness, that he would quietly transition into early retirement with a generous pension, it soon had to discard such fantasy, for after his downfall he filed three successful appeals over several years against the Ministry of War. Still, Mussolini’s henchmen persisted in denying him justice until 1935 when, in the face of the government-issued circulars announcing Black and mixed-race persons could not command white Italian soldiers (and shortly thereafter race laws mimicking those decreed in Nazi Germany), Mondelli understood further resistance was pointless. Nonetheless, he had been the only one of the four Black WWI officers to challenge his nation’s fascist rulers.

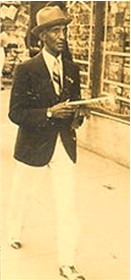

Save for his three appeals, Mondelli essentially spent the interwar decades uneventfully with his wife and two daughters in Rome. He refrained from involvement in politics. He must have had an opinion about Italy’s foreign adventurism, in particular the Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-1936), but he didn’t broadcast it. Thankfully, when American and British troops marched into Rome in June 1944, effectively terminating Italy’s military role in World War II, Mondelli could safely resume a more normal life.

Restoration

In the post-war era Mondelli flourished as a Mason and by 1956 had reached the pinnacle in the order as a 33rd degree member. Several high military honours followed. In 1968 he was made Army Corps General (equivalent to a 3-star lieutenant general). His final honour occurred in 1970 when he was awarded the title of Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic by then President of the Republic Giuseppe Saragat, a staunch socialist who had survived persecution by the fascists. It has been asserted that this last honour was given in large part as compensation for those wasted interwar years in which he had been victimised by Italian fascism. He made some film appearances (including a documentary on Africans in Italy) and resided in Rome in via Milazzo in the Appio Latino district while his wife and daughters settled in Naples. At age 88, Mondelli died in Rome’s Celio Military Hospital on December 13, 1974.

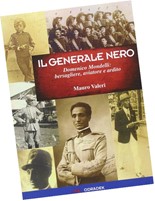

In his 2016 biography of the Black general entitled Il Generale Nero: Bersagliere, Aviatore e Ardito (roughly translated as The Black General: Domenico Mondelli: Soldier, Airman and Bold) by Prof. Mauro Valeri, it was mentioned that Michele Carchidio, one of the three other Black or biracial World War I-era officers who suffered career-ending discrimination but dared not protest, appreciated Mondelli’s ultimate triumph and acknowledged a simple distinguishing fact when he confided in a letter to a friend: “I didn’t make it, Domenico Mondelli did.”

I consider him as a hero. where about his surviving family.members?