Edna Adan: Afropean’s First Lady

By Tommy Evans

One of my heroes in the Afropean universe, Edna Adan, recently took to the stage at the Southbank Centre as part of the Africa Utopia festival. I should have been convalescing after (minor) surgery the day before, but the opportunity to meet an inspiring activist committed to delivering healthcare for all at the grand old age of 77 was too good to miss. Those who have witnessed Edna lecture will know she is a passionate orator and captivating storyteller, so our interview was very much a case of pressing record and letting her flow. Nevertheless, time was very brief so conversation centered on Edna’s early career as a medical graduate returning to a newly independent Somaliland and the subsequent challenges of practicing midwifery in a developing country. If I ever get the chance to meet Edna again, I would ask how she left her life of luxury for the ‘beautiful struggle’ and ultimately succeeded in establishing her nation’s first maternity hospital – whilst ‘retired’. So in the meantime, enjoy what we hope will be a prequel.

Tommy Evans: I thought we’d start with a discussion about firsts: you were the first bouncy castle for sale Somali lady to study as a midwife in the UK.

Edna Adan: Yes, that’s right.

TE: The first woman to drive in Somaliland.

EA: Yes.

TE: You were a First Lady.

EA: Well, my husband was Prime Minister, yes.

TE: The first female government minister.

EA: Cabinet minister, yes.

TE: You set up the first maternity hospital in Somaliland.

EA: A private initiative, yes.

TE: And, you were the first Somali woman to travel on Air Force One.

EA: I did, yes!

TE: So what was it like as a young woman from east Africa coming to live and study in the UK?

EA: Well, I first came out to England in 1954. I was on a colonial welfare and development scholarship and there was another young lady from Aden (a port in Yemen and a crown colony of Britain); the two of us were sent here with a whole bunch of other boys and we studied at the Borough Polytechnic –

TE: Which is now London South Bank University.

EA: Of course.

TE: Where I’ve studied too.

EA: There you are! We did our pre-nursing course there because our English wasn’t good enough and we were too young. We had to be at least 18 before we could start nursing in those days so to fill all that up you were sent to the Borough Polytechnic. From there I went on to do my nursing at a hospital that is no longer in existence – the West London Hospital of Hammersmith – and after graduating as a general registered nurse I went on to do my midwifery at the Hammersmith Hospital in Ducane Road. I did further specialisation at Lewisham, did oncology at St. Marks, diseases of the chest at Clare Hall Hospital, Hertfordshire and also did some further studies in administration at West Middlesex.

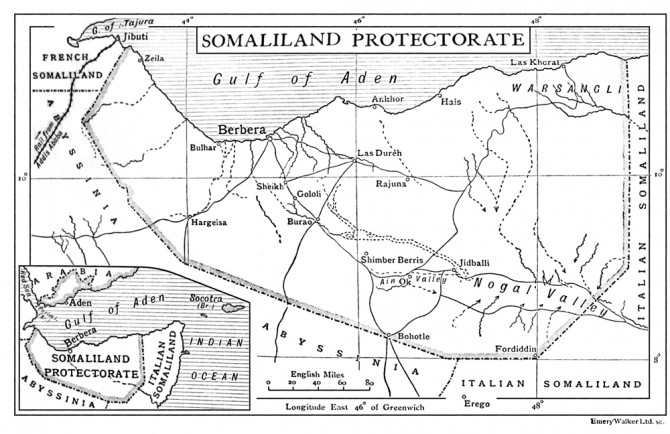

Then, in 1961, after Somaliland had become independent in 1960 (Somaliland is the former British Protectorate of Somaliland), it was time for me to go home. In fact, our late president Mohamed Ibrahim Egal (Edna’s former husband), who had been a student here when I first came out, had become the first president of an independent Somali nation and then united with Somalia (the former Italian colony), which was the plan to unite all Somali speaking countries. And Somaliland, being the first-born independent country, waited for the independence of neighbouring Italian Somalia and when Italian Somalia also became politically united, I went back in 1961 to a Somalia.

TE: Was there a bit of a culture shock?

EA: It was a culture shock coming from there to here; the language was different, the culture was different, the climate was different, the food was different and in those days there weren’t that many black people so very often I would be the only black face in class. And it was very important for me to do my best, first because I wanted to prove to my parents that allowing me to come here was not a bad thing and I was not going to bring all those embarrassments and shame that women predicted I would bring upon my mother if she allowed me to come to England. So I had to make sure that I did not become all the things that they said I would become but, on the contrary, the education and opportunity that was given to me was going to give something back to me, my family and my country. So you have those standards to maintain. And then being the only foreigner, or the only black face in the class, also makes you hold on to even higher standards to prove to everybody that, “Yes, my skin is different, my skin is black but my brain is not deficient.” So, you become very competitive! I loved studying, I loved what I was being taught, so it was not really that hard – I still love learning. And you make friends, you mix with people – I love people, any colour, whatever background – and that’s how I spent seven years or more as a student at different institutions.

And then going back, there was a reverse shock again. Going to a hospital that had no equipment, going to a hospital that had no hierarchy, there was no order, there was nothing! I went back asking, “Okay, what would you like me to do?” expecting that someone would tell me the brief, my terms of reference, all my job descriptions, what I was entitled to and what I was expected to perform – but there was nothing. So I had to set my own standards and I had to just do things the best way I could, the best way I knew how and that’s how you just get on. And then you realise that, whatever you do, you must never put yourself in a position where – how should I say – you look down upon others; I am neither superior nor inferior to anybody, I’m just a person. I may do some things better than some and many people do other things far better than I can, so I’m just a little person in this great big humanity who’s trying to do my share, my little bit to the best of my abilities and you gain respect and you gain confidence.

Let me share a little story with you. A few months after I went home, one of my uncles came to me at five in the morning, banging on the door saying, “Quick! Quick! Quick! Quick! Khariya’s having a baby and you have to go there!”

I said, “Well, where is Khariya? Why didn’t the hospital call me?” (If the person is in the hospital and they have a problem the hospital used to call me.)

“She’s in the house.”

I said, “Why is she not in the hospital?”

“But this is Khariya!”

Now, I don’t know who Khariya is, but if she’s having a problem, she should be in a hospital. But then I couldn’t argue with my uncle so I said, “Let’s go find out what the problem is.”

I went to the hospital, grabbed my bag and was driven to Khariya’s house, where a dozen women were around Khariya. And Khariya had given birth to a baby but the placenta was still inside so I said, “Do you mind if I examine her?” because I needed people out of the room so, “Please, If you guys will excuse me!”

Now I’m very small and I was very thin in those days – it’s hard to imagine now – and they looked at me and thought, “We’re going to trust Khariya with this skinny little thing!?”

But I’m all they had. So one or two remained, the others went out and I examined her. And all Khariya had was a full bladder that was obstructing the placenta so I put in the catheter, drew out a liter of urine and just delivered the placenta uneventfully. Now the certificates and diplomas I had from Hammersmith Hospital, Lewisham Hospital didn’t carry any weight; delivering Khariya of the placenta that many other midwives had failed to get out – that was my qualification. I was really someone who could do something that they could not.

So that opens doors, which gives you confidence and once you get the confidence of the people you build on that. For instance, you’re just one pair of hands and you’ve got to do this and that and a hundred other things so I went to some of the girls I used to teach at school and said, “Look, I need you to come and help me on Wednesdays when I have antenatal clinic.” All they would do is just fill the register of the names of the women, their ages and their details so this would give me more time to look at them. But I would have to go seek permission from the father for this young lady to come help me on a Wednesday afternoon at the prenatal clinic. I’d assure the father that, “No, she will not touch sick people,” “No, his daughter will not be working with men,” “No his daughter will not get out of my sight,” “No his daughter is not going to get up to any mischief” – she’s just going to fill registers for me and put the women in line and get them in to see me one at a time.

“I promise you, that’s all your daughter is going to do!”

So, he said, “Okay, if that’s it, then she’s fine.”

Then I need another girl to come and help me wash the newborn babies. And I go to another father to say, “Can I have your daughter to help me and come in the mornings, maybe for an hour or two just to give a bath to the newborn babies?”

“Oh, no, no, no – I don’t want my daughter to work in a hospital.”

I said, “No, she’s not going to work in a hospital, she’s going to work in a maternity ward and she’s going to wash the newborn babies. I promise you they’re not sick, they’re not infectious, they have no disease – and you want your daughter to marry and have kids one day and to know how to look after little babies, right? Well, this is going to give her that experience.”

That’s how I got the second one! One step at a time you get people to come and collaborate with you, your family of assistants grows and the confidence of the community grows.

TE: One final question, as I know you have to dash off. There’s a brilliant photograph of you and your husband with the former American President, Lyndon B. Johnson, and I was wondering what was more amazing for you: being the first Somali woman to drive or to fly on Air Force One?

EA: Building my hospital was far more exciting! Opening my hospital on the ninth of March 2002, that was more awesome.

www.ednahospital.org

Thanks to Nicola Jeffs at the Southbank Centre for hooking up the interview.