Election day – The Migrant’s Vote for Integration

By Zdena Mtetwa-Middernacht

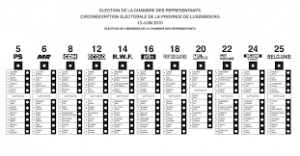

It is Election Day in Belgium. I am not voting but I’ve taken the walk to the polling station. The polling station is a school a few hundred metres from our home, in a little Flemish town on the outskirts of Brussels. I’m at the playground with the kids while my husband is voting. It’s a sunny autumn morning and I am feeling strangely out of place. I’m trying to work out the reason why. Perhaps I’ll ask someone who might be able to relate, but I see no visible people from an ethnic minority around me. I can’t make this a conclusion though, because I haven’t been at the polling station long enough, perhaps some ethnic minorities already came in to vote before us and perhaps others will come after we’ve left. And by the way, I could have voted.

I was invited to register to vote, but I missed the deadline. That was my fault. This is a comforting thought, but I’m still quite anxious to leave this place. Nevertheless, I once again engage in the painful task of putting things in perspective as I perennially have to do to navigate the kinds of spaces I occupy.

The official understanding of integration is limited to expecting the ‘immigrant’ to prove their level of assimilation, rather than collectively facilitating integration in the true sense. When you have been living in Belgium for a number of years, you qualify to vote, even before you are a Belgian national. The process of becoming a Belgian national in itself includes a requirement to prove your integration in several ways. You may need to attend an integration course that teaches you about different aspects of Belgian life for example, or you may need to take a language test to prove your language proficiency in the applicable language. Applicability means that you may have a good level of French, but depending on where you live, the applicable language may be Dutch, or vice versa. Personally while I find the language politics strange (to say the least), I don’t find the actual requirements unreasonable or unattainable. In any case, I think that giving permanent residents the right to vote is positive and is in itself a good way to facilitate integration. In fact, I cannot imagine a better way to publicly proclaim a place as one’s home than the act of voting. Casting a vote means that I have embraced a place as my home, so much so that I am willing to participate in shaping the collective future of that home. Why would one feel awkward on such an important occasion?

I dare say that this feeling may have less to do with me as an immigrant than it does with the collective. I can tick all the boxes of integration and be awarded an integration certificate. But if the national narrative is to ‘other’ me, problematise my presence and base political discussions on finding ‘solutions’ to my presence; can I ever be truly integrated? My integration depends on the others around me as much as it depends on me. I cannot fully belong until the others around me say I belong. I am coming to understand that it is possible to feel at home in a place but feel very uncomfortable publicly proclaiming that place as your home, when you are not part of its collective memory (or if you are, then the collective memory of you is that of the ‘unwanted other’).

The policy of making permanent residents eligible to vote is at least inclusive and even progressive. However, the politics at play makes the process almost schizophrenic, particularly for the ‘visible immigrant’, the person of colour (the PoC). The PoC is invited to vote, he/she stands in a queue, to publicly proclaim a community as his/her home, surrounded by those who are there to vote for something to be done about his/her presence there, and many who are curious to know where he/she ‘is really from’.

Where does this leave us?

It leaves us in a place where integration must be seen as more than an administrative process, a unidirectional effort by the immigrant to fulfil certain requirements that allow the administrators to tick the required box to grant more rights to that immigrant.

Rather, true integration should be seen as a process of facilitating a home-making process, which, while obliging the immigrant to learn a language, and take part in the culture of the host country, also educates the hosts to complete that process. The educational gap that has brought us here in the first place needs to be addressed. Closing that gap means acknowledging that part of Europe’s history happened overseas, through colonialism, enslavement and the slave trade and it is important that Europeans understand what that means. It means clarifying that migration is ‘normal’, that human beings have been migrating since the beginning of time and that Belgians are also immigrants in other countries, including in the Congo.

In terms of integration, I can only ever complete half of this process, and unless the hosts complete the other half, the process can never be complete. That in itself cultivates a new set of problems which I will not discuss here.

History is in the present, and when it comes to the issue of migration, unless there is a full understanding of history, the immigrant will be invited to the polling station, only to stand with those who ask them what they are doing there, even if only with the sound of their stares.

Zdena Mtetwa-Middernacht is a Zimbabwean woman living in Belgium. She is a PhD candidate at the University of Kent with a focus on migration and transnationalism. Zdena also works as a Researcher for Organisation Development Support (ODS) in Brussels.