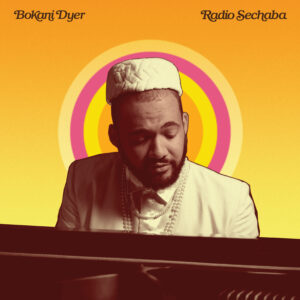

Finding Home, Politicised Art and the Resonance of Truth: An Interview with Bokani Dyer

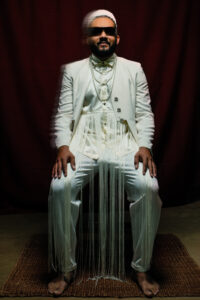

My interview with South African Jazz pianist, composer, and vocalist, Bokani Dyer is off to an inauspicious start. Both of us are having freak tech issues. The interview ends up being delayed by a couple of hours. Much to my relief, Bokani is serenely gracious about it all. Once order is restored, he joins me to discuss his new album Radio Secheba, released on Brownswood Recordings in May.

Was the choice to play the piano about carving out a distinctive musical identity?

‘I was just drawn to the piano’ Dyer recounts ‘It’s mysterious. At my high school in Botswana, I asked this guy I met in one of the practice rooms to teach me some piano. Before formal lessons, I was learning Janet Jackson songs from this dude who was completely self-taught by ear. When he wasn’t there, I would still practise but with no instruction, no strategy…none of that stuff. I started composing before I knew what I was doing.’

Does he remember the first song he wrote?

‘Oh crazy!’ he reminisces, bemused ‘I have an early memory of something I ended up calling The Morning After…I was probably trying to be cheeky but it was completely innocent. I can’t remember how it goes.’

Dyer’s musical DNA – as he would put it – continued to be shaped by a close, younger relative of Jazz.

‘The whole Neo-Soul movement was huge for me’ Bokani recalls ‘I pinpoint the Voodoo album by D’Angelo as the one where I felt “if this is what music is, I want to be here”. To this day, I can’t say enough good things about it’

The Neo-Soul scene and its derivatives have also left an indelible imprint on Bokani’s vocal style. He counts Erykah Badu, Glen Lewis and Carl Thomas amongst his inspirations, as well as bygone titans such as Nat King Cole and Donny Hathaway. Moses Sumney and Jordan Rakei are more contemporary influences. It might come as a surprise that, despite a clear similarity in cadence which he acknowledges, Dyer is not especially drawn to the music of John Legend. Neither is he one for the sort of sentimentality that has propelled Legend’s career. More on that later.

As for his formation as a pianist, Bokani lists amongst early favourites South African composer and multi-instrumentalist, Bheki Mseleku, Bill Evans, Michel Petrucciani and in particular, Ahmad Jamal. Bokani considers the recently-departed Jazz pioneer to have been… ‘…one of the most prolific but underrated artists. I guess it just happens sometimes. It doesn’t get picked up by the droves.’

A conservatoire-trained and award-winning Jazz musician himself, Dyer’s music is a 21st Century iteration of the Fusion movement. He’s not precious about embracing R&B sensibilities or interloping strong elements of Afro-Funk and House. He is a self-professed “anti-elitist”.

‘With Radio Sechaba, I decided “Screw it. I’ll do what I want to do”, he says.

So far, so confident but the decision came with its qualms.

‘There were times where I felt apprehensive; is this going to make sense?’ Dyer confides ‘We exist in a context. You check out the scene and say “How is this going to fit with what’s going on?”.’

To that end, Bokani considers himself fortunate to be signed to Brownswood.

‘I feel they’re the perfect label. It follows Gilles Peterson’s legacy as a selector and tastemaker. In 2018, I watched him in New York play everything during a four and a half hour set. I thought “This is the musical world I want to live in!”’

South Africa often seems to be at the vanguard of a vibrant music scene; from internationally-acclaimed acapella choirs and world-dominating permutations of House, to modern day Fusion acts like EMAMKAY and of course, Dyer. How does he position himself within the current musical landscape? Not for the first time, he takes a slight digression.

‘They’re a lot of people trying out new things. Forging an identity is a big issue. They’re looking to dismantle the hangover from a colonial past in a really honest and positive way. They’re not afraid to be themselves and to express what they feel’.

Bokani contrasts this with previous generations. ‘I remember speaking to older musicians, who’d advise me when travelling overseas to just make sure I’m giving that “African flavour”. It didn’t sit well with me but now I can understand why. It’s about marketing. You think “I’m going to ramp up the African-ness of my music so that it is so unique, the Western world can more readily consume it”. As an artist, it’s important for you to have the licence to go where your heart leads. It shouldn’t be a situation where Africans are trying too hard to be African. Does that make sense?’

Radio Sechaba is an album of understated beauty; a slow-burner. If one track instantaneously penetrates the soul, it is single Resonance of Truth. The second movement in particular, seems touched by the Divine. The word transcendent comes to mind. Dyer’s lyrics cover a refreshing breadth of subjects. The search for truth is a refrain throughout the project. Specific to Resonance… Bokani speaks of self-liberation from people-pleasing. What was his state of mind when creating the record?

‘I’m going a bit of a distance from your question but will come back to it’ Dyer warns, good-naturedly ‘I use the idea of ‘home’ quite a lot on different tracks. That’s about feeling displaced, as in, being at home within yourself. Living in this social media generation, it seems people are almost destroying themselves to please others. It’s one of the afflictions of our time. We can see that in the mental health struggles of so many. When I was writing Resonance of Truth, the first line was “Be careful not to run far from home”. From that I tied together a story. It was totally instinctive.’

And what, according to Dyer, is the resonance of truth?

‘I am not aligned to any religion but I could liken the idea to “following the Holy Spirit” to help navigate the bumpy terrain of life’s journey. It’s different for each person but that’s how I frame it.’

Returning to the looming historical reality of Apartheid, Dyer was born at a time when the regime was still alive, if ailing. Bokani’s father – of English, Welsh and German extraction – self-exiled to Botswana, after refusing to serve a compulsory stint in the South African army as part of his national service.

Seven-year old Dyer returned to South Africa a year before Nelson Mandela’s election as president and the official end of Apartheid. Dyer’s music has a noticeable political thread. In light of his father’s own activism, did it necessitate a view of art as a site of political expression?

‘It doesn’t necessitate anything’ he counters ‘It’s more because of where I was and what I was thinking about at the time. I watched this Nina Simone documentary where she said “An artist’s duty is to reflect the times”. This got me thinking about where I am in my musical process. I was also doing my Master’s whilst making Radio Sechaba. My thesis was on how young composers address social issues through their music. I interviewed a bunch of my contemporary musicians in South Africa and did a deep enquiry about their process; how much they feel that they are addressing matters of social importance’

Identity was once again a leitmotif that emerged during Bokani’s research.

‘Everybody’s trying to figure out who they are. That led me to the decolonisation agenda. Beyond the music, you see it in our society. Rhodes Must Fall…these kinds of youth movements. Even if it’s indirect, musicians are also speaking to some of those issues.’

What would Dyer say to those who believe artists should steer clear of political content?

‘There was quite a big debate on this within the ANC in the late 80s’ he shares ‘Albie Sachs – a well-respected struggle veteran – wrote a paper calling for the end of struggle music. His argument was quite compelling. He said very overt political messaging removes some of the beauty and nuance of what music is. I would not prescribe it but I don’t want to put on music where I’m just hearing political manifestos. With poetic language you can say a lot’

Bokani’s choice to sing in indigenous languages – Setswana, to be precise – could be one such example of making a subtle but unmistakably political statement. Is this something that he consciously embeds in his music?

‘It’s been very conscious. I’ve wanted to get better at Setswana; the only indigenous language I speak fluently. Language carries a lot of culture and also rhythm. It has its own musicality. I wanted to open up that channel of expression for myself. English is a beautiful and vast language but it’s been tainted in certain ways. Some things won’t have the same power in English.’

An excellent example from Radio Sechaba is the haunting Ho Tla Loka. Between vocalist Yonela Mnana’s lachrymose delivery, traditional harmonies and poignant melody, the pathos is almost unbearable. Yet, lyrically it’s more uplifting than it seems.

‘Ho Tla Loka means “Everything will be fine-it will turn out okay”’ Dyer explains ‘To say that in English doesn’t have that same…’

…It would sound trite…

‘Exactly! I can’t give the English translation that conveys the feeling of those words in Setswana’

In several ways, Bokani represents a generation of South Africans born in the dying years of Apartheid; one that glimpsed the old and came of age in the new. How would he compare insights across the generations?

‘I think people choose to let history affect them in different ways’ he proffers ‘In South Africa we are experiencing the traumas of the past. We are also unresolved in that transition towards black leadership – the ANC. That also comes with its own baggage’.

He continues, ‘This is what I speak about in the song Mogaethso. It’s critiquing the leadership. This is the protest song on the album. Our past is still very much with us. The laws have changed to provide for a more equal society to flourish but we’re still dealing with a lot of those issues’.

Bokani reflects further ‘Obviously, people who have direct knowledge or experience of the days of Apartheid will have a different take on it. They felt the full might and oppression of the regime. We [younger generations] hear these stories [but] it’s a different level of attachment. It’s up to the artist to decide how much they want to engage with that or decide to sing about fast cars and how much money they have’ he adds, with a cheeky chortle.

My, is Bokani throwing shade on frivolous commercial fare?

‘No! You know, everybody is free’, he insists, still smiling.

Whilst Radio Sechaba is in no way Dyer’s first rodeo, he sees it as a fresh, stand-alone concept.

‘It is its own thing, as oppose to my trio work. I recorded the album and also started the band of the same name. They have grown into the music and taken it somewhere else. My focus now is on the project; writing new music, developing the show and travelling the world with it. We did our Radio Sechaba launch in Johannesburg last week which was great.’

There is talk of European tour dates this autumn and a Volume II studio album is envisaged for 2024.

Bokani concludes, ‘I feel there’s more that can come of it, more to add to the story’.

Radio Sechaba by Bokani Dyer – out now on Brownswood Recordings.

This is an edited version of an extended interview first published on the I Was Just Thinking… blog