Portrayals of a Queen and a Princess Exalted: The Artist Ben Enwonwu

It is generally acknowledged that the most esteemed and significant African artist in the second half of the 20th century was the modernist, Ben Enwonwu. His career benefited greatly from having sculpted a statue of Queen Elizabeth II and painting three portraits of Nigerian Princess, Adetutu Ademiluyi, when both women were in their 20s. There were quite a few other artistic works that assisted in bringing him international acclaim. However, it was his portrayals of these noblewomen that accelerated the trajectory of his career and, in the case of Princess Ademiluyi, famously endeared him to his compatriots.

Born Odinigwe Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu on 14 July 1917 into a relatively affluent family in Onitsha, Anambra, Nigeria, as early as age three he demonstrated something he believed he naturally shared with his engineer father: sculpting. His mother and grandmother recounted how, as a child, he littered their home with bamboo and wood chips. Enwonwu himself admitted that early on he was obsessed with sculpture, carving and moulding his own toys, buildings, animals and more; all that which inhabited the child’s world he created and called “Man”.

By the time he entered Government College (secondary school) he had already experimented with clay, alabaster, and bronze. Tutored by Kenneth C. Murray, a British colonial civil servant, upon graduation in 1939 he was hired to teach art at the school. The upshot of his successful one-man exhibition in Benin and Lagos in 1942 was a scholarship that allowed him to travel to London to study at the Slade School of Art, and later at Oxford University, to earn a degree in Anthropology.

In 1948, Ben Enwonwu was appointed art supervisor to advise the colonial government on matters pertaining to art and act as a sort of ambassador when abroad. He made frequent trips to Europe that kept him abreast of that art scene. In 1950, he went to the United States where, among other places, his exhibitions at Howard University in Washington, D.C., the Schweitzer Festival in Boston, and Roosevelt House in New York City were warmly received. Returning home from his American triumph, he resumed his duties as a civil servant, made additional tours of Europe, and earned more awards, commissions, and recognition.

The Politics of Fame

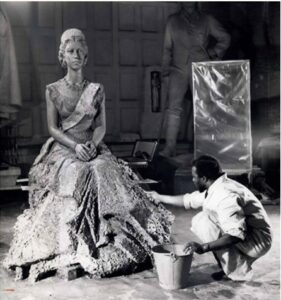

Dwarfed by oversized, dramatically posed statues in a borrowed London studio, Enwonwu moved methodically, occasionally tilting his head and repositioning his body to better mould and evaluate his creation before his distinguished model arrived for another sitting.

A year earlier in 1956, when Queen Elizabeth II visited Nigeria, it was Enwonwu himself, in his role as an art consultant in the provisional Nigerian government, who first proposed sculpting a likeness of Her Majesty to mark the event. Alan Boyd, Secretary of State for the colonies, approved the idea and a commission was offered. The project would be a win-win for both government authorities and the artist. British proponents of empire and the continuance of a sprawling but shrinking British Commonwealth, and influential Nigerians who saw themselves advancing inexorably toward independence, were of the opinion that a statue of the Queen done by a native Nigerian would symbolise and cement bonds of friendship and goodwill between nations- or so it was hoped. Few may have understood at the time that this would be the first artistic rendering of a member of European royalty by an African artist. For the already well-appreciated Enwonwu, a political moderate who embraced Negritude and Pan-Africanism, such an enterprise could mean a tremendous career boost, the extent of which he could only have guessed.

Enwonwu at work on the late Queen Elizabeth II’s statue

Having settled matters pertaining to protocol, Enwonwu relocated to Buckingham Palace where, starting in March 1957, the Queen’s first five sittings occurred. These were followed by seven additional sittings at the private studio of Sir William Reid-Dick. He made a watercolour profile and frontal sketches of the Queen, modelled clay busts of her, and was careful to shroud his work with cloth sheets until he was ready for the public to view it. The artist admitted to being in awe of his subject, and though he had to direct the Queen’s poses and touch the royal body he found her cooperative and considerate. She even relieved whatever discomfort he felt by initiating pleasant, reassuring conversation and made comforting inquiries about his family members. Sylvester Ogbeche, Enwonwu’s principal biographer, wrote that: ‘. . . between March and May 1957, the interaction between artist and model would become somewhat informal and the Queen humanised. Enwonwu described the young Elizabeth as a shy yet charming woman, thus showing that he penetrated her public visage despite the stern gaze of the Royal chaperones who were present in all these instances.’

A photo in the New York Times, 30 November 1957, subsequently appearing in a number of other publications, showed Enwonwu and the Queen standing together peering upward at her statue which was unveiled in London at the exhibition of the Royal Society of British Artists (RSBA). A bit larger than life size and formally attired and bejewelled, the monarch’s face is oddly serene, nearly expressionless. She is seated, bedecked with regal sash, tiara, and a spreading gown. When the commission to portray the Queen was announced—something the British press downplayed- a reporter for the West African judged it as conferring ‘the royal seal on the renown of West Africa’s most famous artist’. Indeed it did, as Enwonwu’s status among the world’s great artists skyrocketed. However, there was grumbling from some quarters.

British traditionalists like one writer for The Times thought the statue evinced the ‘requisite sense of regal dignity’ but left him with a ‘feeling of constraint and lack of vitality.’ Others seemed bothered by the fact that a black African had been allowed to sculpt the Queen. The Daily Mail’s Pierre Jeannerat suggested Enwonwu could not suppress his natural (less “civilized racial”) inclinations, leading him to conclude the ‘likeness is there all right, but I personally feel a distinct Africanisation of the features.’ The “unwelcomed” African features were believed to be most noticeable in the lips and the abstract geometric pattern in the folds of the gown, all of which were said to be more obvious when the statue was viewed close up but were not so apparent from a distance and elevated on a pedestal.

Petty sniping notwithstanding, fellow artists were generous in their praise of Enwonwu’s artistic vision and the project’s execution, including the art critic for The Times. Within months Enwonwu was interviewed on BBC television, was awarded the Bennett Prize by the RSBA and made a member of the prestigious group, received the Commonwealth Certificate of recognition from the Royal Institute of Art, Commerce, and Agriculture, and earned the distinction of M.B.E. (Member of the Order of the British Empire) from the Queen herself. Not to be left behind in the rush to honour him, back home authorities gave Enwonwu the upgraded title of Art Advisor in the Information Service Department of the Nigerian government.

The course of Enwonwu’s personal life in London was in stark contrast to his public image as a tactful, serious-minded visitor. Away from the studio he lived a colourful life. Known to always sport a flower in his lapel, he cruised urban streets in a large, luxury automobile- a flashy American Packard. A rather scandalous affair with his married British personal assistant resulted in her abandoning her husband to live with Enwonwu. Although the affair produced a child, he declined to marry the woman (he later married another British woman, then a Nigerian woman, and fathered nine children). Ogbeche commented: ‘. . . (He) enjoyed an upper-class lifestyle secure in connections and social status. He was a widely travelled cosmopolitan, articulate and firmly convinced of his superiority to many British artists and individuals.’

Intended for placement at the entrance to the Nigerian parliament building, the Queen’s statue arrived at its destination in 1959, a year prior to the nation’s independence from Britain in 1960. The statue seemingly vanished in the upheavals that followed independence until the year 2000, when a British representative of Bonhams’ art auction house discovered it in a room used by caretakers in the Nigerian National Museum in Lagos. It was spruced up and put on display at the British Residence in Ikoyi, Lagos, to be admired by the then Prince of Wales (now King Charles III) when he toured the country in 2018.

Hero of National Unity and Reconciliation

It was love at first sight. Enwonwu couldn’t shake the overpowering attraction to the elegant Princess Adetutu Ademiluyi, the granddaughter of an Ooni (king) of Ife. The long, slender-necked beauty first caught the artist’s attention in 1970 when he taught at a regional university. Though unsuccessful in persuading the royal family to consent to marriage, he was permitted to have her sit for a portrait in 1973. To ensure he would never lose her haunting image, he painted two versions of the original, and we are truly fortunate that he did. Each portrait was titled Tutu.

The hopeful, celebratory mood that ushered in independence from Britain was far overshadowed by the awfulness of the three-year Nigerian Civil War—an ethnic conflict from 1967 to 1970 that wasted the lives of an estimated one million citizens. In the wake of that national catastrophe, there could not have been a more opportune moment for national healers to emerge. Enwonwu was certainly one of them. He was Igbo and his unobtainable romantic interest, the alluring and graceful Princess Ademiluyi (Tutu), was Yoruba. Moreover, the fact that he had personally dealt discreetly and respectfully with Yoruba royalty resonated with those who accepted Tutu as a sincere gesture of reconciliation. It was an effort that comforted a deeply wounded nation.

Portraits of the princess soon became the iconic artistic masterstroke Nigerians could relate to. Prints of the portraits adorned walls in many homes throughout the land. Oliver Enwonwu, the artist’s youngest son, told the Guardian he believed that, in essence, the portrait ‘epitomised what he was trying to push about Africa.’ World-class Nigerian novelist Ben Okri elaborated, ‘Ben Enwonwu wasn’t just painting the girl, he was painting the whole tradition. It’s a symbol of hope and regeneration to Nigeria, it’s a symbol of the phoenix rising’.

Aside from the faint smile and calm, enigmatic countenance of the princess – who wears traditional, stately clothing – there’s another reason why Tutu has repeatedly been described as the African Mona Lisa. Like Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda, the initial Tutu (which Enwonwu considered his supreme masterpiece), secured in his bedroom, was stolen and eventually recovered. Four decades after the first of the two long-disappeared copied versions vanished, it was discovered in an unpretentious London flat in late 2017. The discovery came 23 years after Enwonwu’s death from cancer (a death that may have been hastened by the devastating theft of the original Tutu).

Okri compared its re-emergence to a ‘rare archaeological find . . . the most significant discovery in contemporary African art in over fifty years.’ The art world agreed. Instead of selling for a predicted £300,000, a private buyer paid £1.2 million in a Bonhams’ auction that was concurrently televised in both London and Lagos. At the time, it was the most expensive piece of contemporary Nigerian art ever purchased.

Writing in the Financial Times, bestselling author and art and culture journalist, Charlotte Jansen, thought Enwonwu’s significance was underappreciated, due in large part to his simultaneously straddling the opposing forces of Pan-Africanism and colonial governance. Noted African art historian Bea Gassmann de Sousa has offered her verdict on the artist, ‘He was reluctantly politicised; unwittingly he became a political spokesperson, but away from politics, there are so many works (paintings and sculptures) you can fall in love with. They have a power that rivals any European modernist.’

In his obituary in The Independent, Enwonwu was lionised as the ‘leading light in Nigeria’s aggregation of contemporary artists’, his creations enhancing the homes of private collectors and enriching museums worldwide. Prior to the ascent of Enwonwu it had been assumed that an African could hardly suppress his “primitive” impulses and “indigenous traditions” to master classical (Western) realism, but he confounded those doubters by merging the two artistic idioms. He was always conscious of his role as a pioneering modernist and an inspiration to Black artists everywhere. With the statue of Queen Elizabeth II he was said to have “arrived” on the international stage, whilst his paintings of Princess Ademiluyi had made him a household name in Nigeria.

Another award-winning novelist, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, joined the chorus of prominent Nigerians in declaring Enwonwu’s artwork a veritable component of national identity. Few have testified to this as emphatically and intimately as the banker and art collector Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede, who recalled, ‘My parents gave me an Enwonwu print as a child . . . Enwonwu’s work interprets African culture and tradition with sophistication and universal appeal. Beyond the intrinsic beauty of an Enwonwu, his unabashed Africanism fills me with pride.’