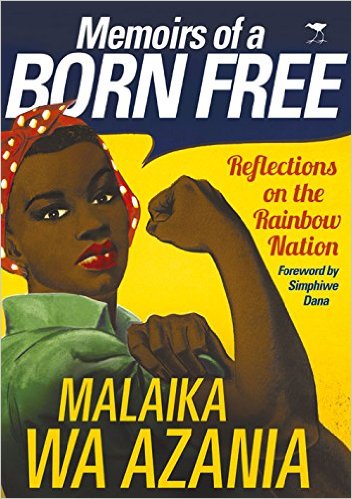

Instant Classics: ‘Memoirs of a Born Free’ by Malaika Wa Azania

By Abena Clarke

Having read about the phenomenon of the ‘Born Frees’ from abroad, and giggled at Cape Town-based blogger Tawanda’s take on the notion, I was very pleased to come face-to-face with some Born Frees when in South Africa. Even more luck befell me when I had the opportunity to attend the Eastern Cape book launch of ‘Memoirs of a Born Free’ by Malaika Wa Azania.

As I understand it, Born Frees are a somewhat romanticised way of describing young South Africans born after apartheid, and particularly after Mandela was elected in 1994. During the period of apartheid, Azania was the name activists used instead of South Africa; SA was a geographical description not a name, they argued. Azania was to be the new name of the country they were trying to build, in which the majority of the people would be ‘free’. ‘Wa’ means ‘from’, I was told.

‘Memoirs’ is the story of a young South African activist’s journey to a political home via ‘a letter to the ANC’. To a foreigner not especially acquainted with the local political history, the author offers an insider’s take on current political formations in South Africa, and an alternative view of ‘the end’ of apartheid.

Wa Azania’s tale is especially compelling given her unique location in history: she is the daughter of a committed apartheid-era ANC activist, and grew up in the townships around Soweto ‘after apartheid’. She grew up increasingly disillusioned. Her grandmother had long lost faith in The Party, but her mother was a full-time activist for much of her youth. Malaika’s story is must-read for anyone interested in the before and after of democratic South Africa.

However Wa Azania is also a writer; a popular newspaper columnist and a ‘comms’ person. As such, her book is well written and features a fully human, youthful black feminist voice. ‘Memoirs’ is both a story about a family, and a story about a changing political landscape and how people reorient themselves on shifting sands. Wa Azania’s tale re-centres the people with far less bitterness than one might expect.

Slightly reminiscent of ‘Wild Swans’ by Jung Chang in the way it deals with three generations of non-conformist women living through a particular historical phenomenon, without giving too much away, Wa Azania is also an activist, and it is on this plane that I connected with her story.

For those of us who are children of a movement, i.e. whose parents believed in ideals that they never set aside for material success, political expediency or despite shifts in political paradigms, today’s world is a harsh place. We’re talented but not built for corporations and conformity, and we’re too idealistic for petty party politics. But we’re not apathetic.

We are those John Blake calls ‘the Children’ – and grandchildren – of the movement. We may use Facebook daily on our smartphones, but we also read Biko and Fanon, while listening to music that enlightens and inspires. We hear and believe in young people, but we don’t have a set place in contemporary party politics. And we’re not sure we really want one. Perhaps because our parents got too close, got burned and we have no desire to jump into a shark pool. Or perhaps because we are rebels.

I conversed once with Cameron Duodu, a Ghanaian journalist who was present at the 1960 Congolese independence ceremony. He remembers Lumumba, and underlined that Lumumba was in the position of forming a government in a country that had four or five people with a university education and a lot of nationalists; people determined to create a fair ‘system’ which would serve the majority of the people of the Congo. Today’s neo-colonial governments, we concluded, were filled with university-educated people, but no nationalists. As a Nigerian friend put it, ‘everybody wants a slice of the national pie’. But nobody wants to cook it.

At the book launch, the young people in the auditorium at the Steve Biko Centre articulated grievances about some of the untruths that they felt subjected to. Narratives that did not reflect their lived experiences. Ideologies that they simply did not buy into. Malaika Wa Azania asked those present whether those of us interested in social change, transformative egalitarian change, were married to the vehicle we hoped would bring that change, or the change itself. Truth-telling, the young people agreed, was imperative.

The following statements, made by the young people conversing that evening, made me pause for thought:

1) There is no ‘rainbow nation’ in South Africa, let us stop fooling ourselves.

2) Whichever way the light hits a rainbow, the colours are always fixed in the same place. Blue never becomes red or orange or yellow. Green never bleeds into purple. The hierarchy between the colours never changes nor do they swap places, even momentarily.

3) I don’t believe there are born frees because even if you grow up black in South Africa with all the privilege in the world, at some point surely you must ask yourself ‘If I am truly free, why do my people continue to be on the periphery of economic activity? Why do my people continue to be at the periphery of knowledge generation?’

Written by Abena Clarke

Abena Clarke is a Caribbean-based London-born teacher, writer, historian and armchair activist. She currently lives in the French Caribbean and muses on identity, belonging and backpacking on her blog movingblack. https://movingblack.wordpress.com