Rescued From Oblivion: Lope Martin, Master of the High Seas

Written by Robert Fikes, Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

Thankfully, and at long last, the amazing story of an unusually gifted and resourceful Afro-Portuguese man named Lope Martin was presented to the world in 2021. Arguably the most consequential of all Black explorers of sub-Saharan ancestry, his unprecedented nautical achievement in 1565 helped streamline world commerce, thus demanding universal acknowledgement. There is sufficient documented evidence to prove he led an exciting life, to say the least. And the plot hatched centuries ago to kill him, to discredit him, and to erase memory of him ultimately failed.

The Portuguese initiated the slave trade in 1444 in West Africa when 235 natives were transported to Portugal, from the area we now call Nigeria. It was a grim existence for any person of African descent in the port cities of Europe in the early decades of the 16th century. Menial labor for them was the order of the day. Likely born in the Algarve on the southern coast of Portugal, there is no background information on Martin’s slave and white ancestors that made compatriots classify him a free mulatto. The exact date of his birth and the place and date of his death have not been ascertained; and there is no artist’s portrait of Martin for us to contemplate. He worked the docks loading domestic and foreign ships and performing other dangerous, backbreaking tasks attending them, but unlike the longshoremen and rough sailors with whom he interacted, Martin possessed keen intelligence and ambition that compelled him to better his lot.

During the so-called Age of Discovery (or Age of Exploration) the evolution of sea navigation advanced technologically to the extent that prospective ship officers had to undergo formal training and examination before certification at the House of Trade in Seville, particularly pilots (navigators) who had to learn mathematics, cartography, astronomy, and master instruments to determine north-south latitude and the trickier triangulation of east-west longitude.

A quick study, Martin surpassed other students in the mastery of instrumentation and earned the reputation as one of Europe’s most competent licensed pilots. So, naturally, when Spain secretly committed to assembling a small fleet to outmanoeuvre Portugal, its formidable competitor that essentially operated a trade monopoly in Asia, no less a figure than King Phillip II personally dispatched Martin, a married man who artfully deceived everyone into believing he was born in Spain, to the secluded port town of Barra de Navidad, Mexico (Nueva España). He was to serve with a ‘dream team’ of captains and pilots aboard the four vessels constructed there who were directed to execute the first-ever round trip from the Americas to the Orient and back, and in doing so establish bases of operation to facilitate future expeditions.

Such a voyage was inherently fraught with peril. The initial goal was to reach the Spice Islands (the Moluccas, east of Indonesia) where two of Ferdinand Magellan’s fleet ships had landed in 1521. One expected inclement weather but also worrying were treacherous currents, shipwreck, food shortage, a host of maladies (scurvy, pellegra, malaria), pestilence, vermin, unfamiliar territories, and the possibility of encountering all sorts of scary, unpredictable people and fantastic creatures. The return route back from Asia (called the vuelta) would be more challenging, for it entailed traversing uncharted northern waters and additional weeks under sail.

The historic enterprise commenced on the dark early morning of November 21, 1564. Martin was pilot on the fleet’s smallest ship, the 40-ton San Lucas captained by Alonso de Arellano with a crew of twenty. Just ten days out from shore a storm separated the nimble San Lucas from the fleet’s other three ships, including that of fleet commander Miguel López de Legazpi, the enormous flagship galleon San Pedro. Instead of slowing to give the rest of the fleet time to catch up or circle back to try to reconnect, the San Lucas sped in the general direction of the Philippines to wait there until the other ships appeared.

All things considered this seemed the reasonable thing to do. Scarcely could they have imagined then the dire consequences of a rational decision, but Legazpi and his closest subordinates viewed the unintentional separation of the San Lucas from the fleet as a deliberate act of betrayal. They deemed the separation a premeditated conspiracy devised by Martin and Arellano to desert and claim the glory of first landing; an excuse to then enrich themselves by raiding foreign merchant ships; and take full advantage of their head-start to procure exotic commodities from fabled regions in the tropics.

When not scanning the horizon and scouting other islands in the vicinity of Mindanao and Cebu to locate members of the fleet and leaving messages and signs of their whereabouts, Martin and his crew repaired their ship and traded with the natives, but after a month, hope for a rendezvous vanished. They had run out of options and now was the moment to take a deadly gamble: attempt the epic vuelta alone back across the Pacific, a body or water nearly twice the size of the Atlantic Ocean and much more challenging to navigate.

In theory, the return voyage involved weaving up through the Philippine islands until entering open water, then taking advantage of favourable winds that would push the San Lucas into an arc that eventually nudged the 38th parallel before dipping toward North America, skirting the coastline south until finding home port in Mexico. However, lacking the support system of a fleet, immense hardship was certain to occur prior to reaching their destination. In a cramped ship plagued with vermin, inadequately stocked with food and fresh water, its torn sails patched with sailors’ clothing and blankets, Martin’s ragged, ‘virtually naked’ crew suffered starvation, exhaustion, and more, but these miseries did not prevent him from guiding the San Lucas safely to Barre de Navidad, August 9, 1565.

Martin, Arellano, and rest of the crew were hailed as heroes for their successful 9-month round trip. Two months passed before the fleet’s flagship arrived, piloted by the noted friar Andrés de Urdaneta who refused to believe the men of the San Lucas had actually docked in Mexico ahead of him, but the ship’s cargo of cinnamon, silk, porcelain, and other goods associated with Asia affirmed their boast of completing the first vuelta. Though the matter of credibility was settled, Martin’s celebrity status was short-lived. His singular accomplishment quickly morphed into a nightmare.

An investigation of the charge of treason against Martin and Arellano for allegedly abandoning the fleet for selfish motives was supposedly conducted by the colonial court (corrupt members of the Audiencia) in Mexico City. While well connected Arellano, a man of noble birth, left unscathed for Spain to report to the king, and Urdaneta, a favorite of officialdom who kept better records was touted has having pioneered the vuelta, Martin, visibly a man of African descent and of a lower caste, was detained without a protector or friends in high places to shield him from slanderous charges based on circumstantial evidence and hearsay. Instead of an outright conviction, the cynical men who dismissed the case against Martin formulated a stratagem so devious as to put Julius Caesar’s assassins to shame.

The vindictive cabal of colonial bureaucrats who believed the mean rumours and false accusations secretly set in motion a fiendish plan to have Martin, despite his invaluable service to the Crown, delivered to his executioner thousands of miles from Mexico. Knowing that Legazpi, left behind to organize a colony in the Philippines, would gladly harm Martin on sight, they conspired to have him sent on a resupply mission to Cebu. To insure he would accept the assignment they gave him 11,000 ducats to find a sturdy ship and enlist sailors. This was merely a ploy since government funds were routinely misappropriated. Martin did not disappoint. He soon squandered the money and was thrown in jail. With this added leverage the cabal pressured him to sign up to pilot the San Jerónimo to the Philippines. On the ship was a message in a sealed envelope held by the ship’s secretary instructing Legazpi to immediately hang Martin upon arrival.

But this pilot was nobody’s fool. It took a pretty tough man to rise through the ranks of seamen to a respected and responsible position in that brutal era when men of his colour in Europe rarely attained much beyond manual labourer. Not only was Martin a highly proficient navigator, he was quite perceptive, or, to use contemporary vernacular, he had ‘street smarts’ combined with ‘situational awareness’ and could be as ruthless, methodical, and diabolical as any of those who connived to destroy him. He knew the endgame his enemies had in mind and he intended to outwit them and plot his own revenge.

Martin’s one-way voyage from Acapulco to the Philippines began ominously with a violent storm on May 1, 1566. Prior to shipping off he had begun canvassing crew members—many he had hired himself and some not of Spanish birth– about the feasibility of mutiny. He even tried to both cajole and seduce the ship’s captain, the aloof and indecisive Pero Sánchez Pericón, telling him: “You are making a mistake if you think that I will take you to Cebu because the very hour that the general (Legazpi) saw me there, he would hang me on the spot . . . I could take you to Japan, where you can get more than 200,000 ducats and add shine to your lineage.” Like a Shakespearean Iago he manipulated crewmen (130 sailors and soldiers), encouraging their greed and intensifying their animosity toward an already despised captain and his petulant son, Diego Pericón, all to his advantage.

Things came to a head on June 3 after an altercation involving Diego and an admired sailor. That night as Capt. Pericónand Diego slept, the sailor and his comrades burst into their cabin with daggers drawn. Amid loud screams of terror father and son were stabbed to death while Martin and others stood guard outside armed with swords in case someone dared interfere. The following morning the mutineers persuaded a reluctant Sgt. Juan Ortiz de Mosquera to captain the ship. Two-thirds of the way to the Philippines Martin made his next move. He schemed to have Mosquera deposed – ironically accusing him of the double murder of the Pericóns, attempted murder of himself, and sodomy with unnamed men. In the infamous tradition for which pirates and mutineers were renowned, Martin ordered a shackled Mosquera to be tossed overboard.

Having eliminated the final obstacle to his survival and escape plan Martin assumed the positions of both captain and pilot of the San Jerónimo. Thus, he was in a position to control his own destiny and avoid the fate that surely awaited him in Cebu. He may have considered life as a pirate or re-establishing his Portuguese identity and offering his services to Portuguese commercial and military interests in Asia. Unfortunately for him factions within the crew – mutineers, loyalists, and undecideds – remained at odds and it didn’t help that Martin argued with and lost the support of key personnel.

A third uprising occurred on July 21 while Martin and 26 crewmen were ashore at Ujelang Atoll in the Marshall Islands (2,600 miles from the Philippines). Disgruntled rebels, who took control of the ship, were coerced into negotiating with Martin who held ashore two sails and critical nautical equipment. A bargain was struck: sails and nautical equipment for food and water. The San Jerónimo continued on to Cebu. Martin and company were marooned in Micronesia and, subsequently, lost in the dense fog of history.

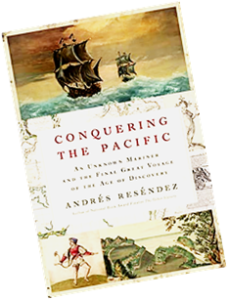

There is some evidence to suggest that Martin may have settled down to live among island natives, was picked up by a passing vessel, or used a large parao (outrigger boat) to relocate him elsewhere. These and other explanations for his disappearance were mentioned by Andrés Reséndez, a distinguished history professor at the University of California at Davis, in his widely acclaimed book Conquering the Pacific: An Unknown Mariner and the Final Great Voyage of the Age of Discovery, published in 2021, which formed the basis for this article. We are indebted to him for rescuing Martin from oblivion and giving him well deserved credit for a monumental achievement.

The significance of Martin’s round trip in the Pacific is that for two centuries Spanish fleets annually retraced the same route, bringing wealth to Spain and assorted products to its foreign possessions. It should not be overlooked that as a free professional man of some distinction he had more agency than any of the better-known descendants of sub-Saharan Africans often portrayed as explorers (e.g., Matthew Henson, James Beckwourth, Juan Garrido). He was an exemplary pilot who out of desperation became a renegade ship’s captain but who nonetheless trailblazed the vuelta which had demonstrable far-ranging, long-term economic repercussions. Small wonder some writers have begun calling Martin the “Columbus of the Pacific” (he also visited and named islands during his travels which impacted mapmaking).

When asked by an interviewer why he focused on Martin in his book, Prof. Reséndez indicated he wanted to help “undo the historical unfairness” done to him and that it was astounding that “only specialists in the early history of the Pacific ever knew Martin existed.” He reflected:

“As the world’s center of gravity is constantly pivoting to the Pacific, we need to understand how it all started. Not with the legendary voyages of Captain James Cook as people often say, but with a sailor completely erased from history.”