“Societies have always had to evolve to survive…”: An Interview with Pulchérie Feupo

Written by Tola Ositelu

*(Translated from the original French. My thanks to Anne-Muriel Kouadio and Pascale Ranson for their additional input).

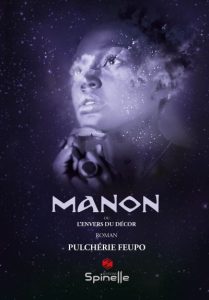

Pulchérie Feupo is a Swiss-Cameroonian author of works for both adults and children. Her latest novel Manon où l’envers du décor (Manon Behind Closed Doors), is a fictionalised account of an impoverished teenager caught up in sexual exploitation. She speaks to Afropean about the narrative she wanted to challenge with Manon…, her work with migrant communities, her hopes for the next generation of young African women, polemics around stereotypical gender roles and her aversion to the ‘F’ word.

First a little bit of background. Where were you born and where did you grow up? What languages do you speak?

I was born in Eastern Cameroon and have been based in Switzerland for around 15 years.

Raised by parents who were senior civil servants, required to travel the length and breadth of the country because of their profession, I grew up all over Cameroon; from East to West, North to South.

In regard to languages, I speak French which is [also] the language in which I write. I studied in English but after 15 years not practising it, I feel more at ease expressing myself in writing than orally. A month in England would be enough for me to get back into the habit. I understand Yemba which I speak a little. That’s it.

I am the author of a number of books. L’Âme meurtrie d’Anouck (Anouck’s Bruised Soul) published in July 2018, Manon où l’envers du décor (Manon Behind Closed Doors), as well as a collection of stories for children Raconte-nous Grand-mère (Tell Us, Grandma). This book introduces children the world over, particularly those from migrant families, to a philosophy which aims to examine self-esteem related issues and constructing one’s identity.

It is published in French and English, with a German translation soon to follow. By way of the interactive story, this collection is an invitation to enter the post-modern African world through the eyes and questions of children, who desire to know and understand.

From where came the idea to approach the subject of sexual exploitation [of a minor] in Manon où l’envers du décor, given that your childhood experience is very different from that of the main character?

I was quite saddened by how banal this scourge had become in my country of origin; to see the young accept it as a normal fact, a practical and “fashionable’ way to [financially] cope. This is in a context where the informal sector becomes the main means of escape for the mass of unemployed. The idea was to call into question what the socio-cultural context tends to normalise.

As mentioned, you have also written children’s books. Obviously, the style and approach would be very different. Were you seeking to step out of your ‘comfort zone’ by writing for an older audience?

I started writing for an adult audience with Anouck’s Bruised Soul which is in fact an essay that became a work of fiction. Writing for children is an old dream which goes back to when I was a coach. Working in this domain, I was struck by how children from migrant families developed self-esteem. There were very few reference points in regards to valuing their cultural background; almost no place in history lessons for stories about the great historical figures of Africa. There was no room given to such tales in the academic programme [to aid] a real [cultural] encounter between children of both Africa and the West.

What kind of research did you do ahead of writing Manon…?

All throughout my career as an educator, I listened to first-hand accounts of women formerly involved in the sex trade, as well as those of their children. They shared their experiences, which for some, had left indelible scars.

In addition, I kept informed via social media and elsewhere. I visited certain areas – not all – where my protagonists would have lived. I looked into the challenges some faced on their journey and sometimes just followed my instinct.

In the novel, it’s the family matriarch who quits the home, whilst the father remains. Were you keen to reverse this particular cliché?

It had nothing to do with reversing that cliché. It came to light in some of the first-hand accounts I gathered, that it was more often women who had the experience of trying to embark on a new life in Europe, with the objective of lifting their family out of destitution.

Manon...is truly harrowing. However, there is a “fairy tale” aspect to the story. Did you add this element as a means of maintaining hope?

To my mind, there is nothing “fairy tale” about it. I’ve been reproached by some of my readers for the tragic nature of the novel.

In an interview with [Swiss broadcaster] Jean-Marc Richard, you spoke of being ‘outraged’ when listening to the accounts of those who romanticise the sex industry. There is considerable controversy around this subject at the moment. Could you expound on your own perspective?

As I see it, when one goes down a road, which very often has the potential to change one’s self-perception…these women who, whether by choice or [financial] constraint, have taken this route, looking at it up close – and avoiding pop psychology – it most often occurs that they develop profound self-esteem issues. Thus, all that remains are the covetous looks they receive from those people who don’t even think to question what road they must have taken [to arrive at that point]. Others’ envy, of their purported successes, helps these women to console themselves; to tell themselves that the deviation was worth it. For them, it’s a form of social approval.

According to the same interview – and evident from your previous profession – you have an affinity with young adults. What do you believe are the specific challenges that face the next generation; young African women and girls, in particular? Would you say that these issues are very different – more significant, even – than those of your own?

I believe that entrepreneurship is the way out and the future for the upcoming generations. They must have confidence in their own inventiveness and from that, create work for themselves and others in a general context where China is occupying an ever more significant position. As women, they should no longer purely commit to preparing to be “good” for marriage, but as providers of work and revenue. Their role and their place in African society today should be interrogated and revised in such a way that they can partake in an ever more competitive and globalised context – where Africa is a little on the sidelines. You must know how to reinvent yourself in order to survive or die by stagnating.

Speaking of the potential of entrepreneurship, this wouldn’t necessarily resolve infrastructural problems such as the lack of widespread access to education or healthcare, for example. It’s an issue of governance. This is all the more evident during the current global health crisis. In your experience, how are the upcoming generation taking on this political challenge; in the Cameroonian context for example?

Entrepreneurship won’t in fact resolve problems of access to healthcare, education and others. However, it will allow for the tackling of mass unemployment through initiatives and the hiring of the workforce required to put certain projects in action. In the first instance, the shareholders could be made up of this workforce – on a voluntary basis – without necessarily having to put up funds.

The stakeholders could thus invest the capital created from this entrepreneurial venture in health and education. All the more so where populations – just to use Cameroon as an example – are left to their own devices by a political system that never ceases to show to the world its stark limitations.

You have said that as an African woman, one “puts up with their status”. Could you elucidate?

As African women, we are defined by our roles as mother, wife and rarely as business director. The current discussions are more focused on the idea of a woman suited to life as a couple. This no longer really cuts it in an economic context which leaves many jobless young men by the wayside. On social media and elsewhere, they debate the concept of a good woman. Either these women embody ideas of having their role and being “protected” by society or they shrug them off and are blamed. To survive over time, societies have always had to evolve. All those that close in on themselves have regressed or disappeared. History is there to remind us of that. China for example, has experienced both aspects.

There are also well-established African feminist movements. Don’t you think these have made a difference?

Personally, I don’t believe in feminism such as an idea [originating] from other continents and applied to Africa. The context and challenges are not the same. I believe in humanism and the simple [golden] rule ‘Don’t do to others what you wouldn’t like them to do to you’.

African feminism has existed for centuries. It’s not all about Western ideologies. This is an argument often put forward by those who want to maintain a patriarchal system in the African context. Moreover, the issues you enumerate above are evident all over the world. Of course, the context is different but there remain shared struggles all the same. Perhaps it’s time to reconsider how you define feminism?

I spoke of a feminism based on European paradigms. It would require an entire interview to go into the detail. Patriarchy and Matriarchy don’t manifest in the same way in Africa. One should know that before the great invasions, Africa was built on a system of liberal ideology where these practices materialised according to region.

Finally, what would you like your readers to take from the novel? Are you hoping to inform the public of this “hidden” reality?

I would like readers to retain some humanity, to step back and reflect on life; the probable and improbable roads of adversity. I would like them to draw from [both] the depth and levity of the content, whatever seems right to them, in fact; that they have the urge to examine the meaning of choice, the good and the less good…

As for the reality that you say is ‘hidden’, know that it isn’t the case in every country. It’s legalised in some [although] it doesn’t make it any less of a crucible of exceptional violence; as much on the psychological level as the physical.

Manon où l’envers du décor – Original French edition available now from Fnac and other retailers.

I admire the valuable information and facts you provide inside your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and also have my youngsters examine up here often. Im very sure they will learn a lot of new things here than anyone else!