The Form

By Daphné Mia Essiet

I was 23 the first time I was asked to officially identify my race.

The day I had to fill that employment form was full of confusion and concerns: I had been

taught in biology that there was no such thing as ‘race’; that we all belonged to humankind. I

stared at the words on the piece of paper: I was only allowed to pick one answer. This was my

first time ever facing this type of situation. Although I was born in the United States, I spent my

formative years in France. Thoughts were rushing through my head: I am not white – but could I

call myself black? I was anxious and afraid to be challenged on either of my choices and face an

already very unfamiliar and uncomfortable situation. Finally, the insistent clerk picked for me

and I went on my way.

Since a young age, people always asked: “Tu es de quelle origine?” or just assumed I was [insert

whatever brown ethnicity they are acquainted with here]. I was several times told I did not look

black. Such remarks always came across as micro-aggressions, ways to impose personal

opinions rooted in stereotypical ideas of what black should look like, and a way for people to

minimize their own cognitive dissonance.

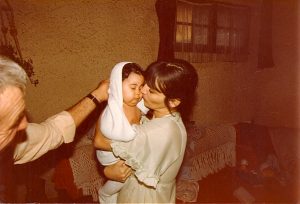

My mother is French and white, and I found out in my twenties that my father is an American-

born Nigerian. Until that discovery, it was never openly acknowledged that I was black,

especially by my mother’s family: a bit like the Lacey Schwartz documentary “A White Lie”, I

had to discover this part of myself on my own. Race was not something discussed in my family,

and in France racial dynamics differ from those in the United States. For that reason, I had little

to no concept of what diversity meant or entailed. Sure, I denoted my difference from other

members of my family and some circumstances emphasized the fact of my difference, but

essentially, I was just one of them.

My interaction with the outside world, however, made it clear that there was something

different about me. I was made aware that my complexion was darker, my body bulky and my

unmanageable hair would never grow long, which made my appearance undesirable within that

context. I felt ugly, fat and poor. I internalized, accepted and carried those qualifiers with me

for a long time. Furthermore, and since there were no black nor mixed race kids around, I had

several times been mistaken for a North African by strangers, which in itself wouldn’t have

meant anything if the narratives about immigrants had been positive. I recall one incident when

the lunch school attendant had refused to serve me pork chops. I could not understand why.

Upset and confused (I LOVED pork chops), I reported the offense to my grandmother. No later

than the next morning, she stormed to the school, outraged by what had happened. At the

time, it was not explained to me why I was refused the meal, but I realized that the way I was

perceived had prevented me from enjoying the same privilege as everybody else: I became

ashamed of what I seemed to represent at a deeper level.

From that moment on, life unraveled awkwardly. I was (and still am) an empath and although it

was not an everyday issue, the unspoken facts surrounding my appearance overshadowed my

existence. I grew up in a middle class white community with little to no diversity; and I would

have been the only exotic bird, had it not been for this beautiful brown little girl named Sana:

she was a first generation French-born Tunisian and pretty ‘woke’ compared to me. She lived in

La Gavotte Peyret projects, but her parents tricked the system by pretending they were living in

my home town so she and her brother could enter my school district. Sana’s father, Moncef, is

probably one of the fieriest personalities I have ever been around. Smart and kind-hearted but

abrasive, never afraid to speak his mind (loudly) and a bit of a revolutionary, he had come to

France from Tunisia when he was a child and had been a brilliant student. Unfortunately, his

own father rejected his ambitious attempts to become an accountant because of a lack of

funds, so he became a mechanic. He was the one who gave us Malcom X’s autobiography to

read in 7th grade and challenged us with geography questions at dinner. Sana’s mother, Naima,

was kind and motherly. She helped me acquire my first admin internship in 9th grade, and later

helped me get myself a job cleaning offices during the school break so I could save and go on

vacation to Tunisia with them. Both hard-working and focused individuals, they were

determined to give to their children anything that hadn’t been afforded to them growing up,

including access to a higher education, as well as a taste for culture and travel. From the time

we met, they had claimed me as their own and even jokingly pretended I was their daughter. I

lived a dual life, where I would alternate vacations between my uncles and aunt in the Alps or

Switzerland, and bus trips with kids from the projects. It was interesting for me to see that

despite their seemingly different livelihoods, how similar they were in many aspects; however,

despite flawlessly ‘passing’ in both worlds, I never felt as if I completely fitted in.

When I was 10 years old, I moved to Corsica to join my mother and her new boyfriend: things

got tricky and I felt extremely isolated. The population of the island is known for being very

conservative and as an outsider – let alone a brown one – it was even harder to make new

friends. At the house it wasn’t any better: when I expressed the difficulties I had encountered in

school I was told by my mother that “it was in my head”. I took it as my cue to keep things to

myself, and as an early teen developed a strong inclination for independence and solitude.

Thankfully, we moved back to the continent when I was 14, and things got a lot better. For

starters, I got back in touch with Sana and old classmates, and although I did not feel like I truly

belonged, the landscape was far more multicultural.

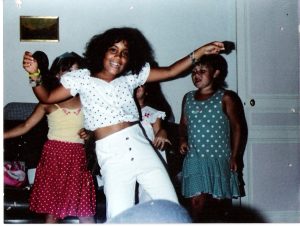

In the early to mid ‘90s new genres were slipping through the radio waves: Hip Hop and New

Jack Swing started their ascension in France’s music charts and we even had own French

rappers such as MC Solaar and IAM. I loved the groove and the energy, however, the cultural

impact was limited. My English was good, but I was not fluent enough to understand what was

said and why it was said. Moreover, there was no access to any types of ‘visuals’ at the time

that could have assisted me in grasping the lyrical meaning.

My pivotal moment happened in 1995, when right before entering high school my mother took

me on my first trip back to the US. I don’t expect anyone to understand how it feels to see for

the first time people who look like they could actually be related to you – your long lost tribe – so prolifically engaging on major media platforms such as TV and magazines. Until then I had never realized how invisible people of colour were in the French landscape. I returned to France a changed teenager.

The Lycée Montgrand high school was located in downtown Marseille. The languages taught in

the school attracted a variety of students from all over and it was the ultimate cultural melting

pot. For the first time in my life I was physically surrounded by a rainbow of complexions.

Youngsters from everywhere: first generation Cape Verdeans, Comorians, Ex-Yugoslavians,

Tunisians, Greeks, Vietnamese, Malagasy, even Brazilians, just to name a few. The ones we

considered ‘white’ were usually second or third generation Italian or Spanish. In my opinion, it

was very integrated – for the most part. Never before had I felt a stronger desire to identify as

‘something’. My English professor explained to the class I had been born in the United States

(my mother had explained in a note why I had missed the first week of high school) and soon

the newsworthy information spread and I became ‘Daphne l’Américaine’, a nickname that

stuck for years to come.

This was not enough – I often had to elaborate about my background. My very limited

cognizance of Black-American culture was based on series like the Cosby Show, the Prince of

Bel Air, Sister Sister etc… and it seemed that in the United States, being black refers to one’s

culture, for instance, individuals who are of African-American descent are considered black

regardless of their complexion or features, even if one of their parents is not – Barack Obama,

Lenny Kravitz, Halle Berry, Tracee Ellis Ross or Alicia Keys to name a few are considered black

even though they have a white parent. This was a concept that was unheard of in France where

‘black’ is only a generic term associated with one’s complexion; people of African descent

always identify themselves by their country of origin and the nuances of their specific tribe

(Senegalese: Peul or Mandiac etc…); and mixed race people like myself are not really

acknowledged as ‘metisse’. So in order to legitimize my blackness (or at least my mixed race

status) my very good friend Sofaya and I decided we would pretend to be each other’s sisters:

this is how after 15 years of blurred lines and uncertainty I finally had concrete answers to the

ever annoying “what are you” questions: I was a ‘metisse Franco-Américaine’. Along with this

newly discovered identity I was eager to learn everything I had never been exposed to. I felt I

had so much to catch up on what I thought it meant to be black. I immersed myself in

everything I could put my hands on: music and TV were the easiest and most accessible means

to do so – we would stay awake late to watch the latest American RnB and rap videos on cable,

exchange cassette tapes and imitate our favorite artists. Later on, in college, I was able to

access more Afrocentric literature and cinematography. Mind you, this was before the internet

and on a teenager’s budget.

There was only so much I could understand from a distance, and although I was somehow

familiar with the black African experience in France, what I knew about the African-American

experience was very superficial. At the time I moved to the United States in 2004 and was asked

to officially ‘claim’ a race, my understanding was still very limited, and I did not know that

although perceived as black, this same blackness would often get challenged due to my – until

then unidentified – light skin privilege.

This experience encouraged me to familiarize myself with and better recognize the racial

dynamics that ruled the social American landscape, it took me a while and a lot of interactions

with different people, but after living in the US for many years, I came to some conclusions of

my own. Mainly that it is complicated and that my specific set of lenses allows me a unique

perspective. Finally, although I acknowledge race and gender are social constructs, I am also

aware that stenotypes associated with it have real socio-economic consequences in the real

world. Ultimately, my racial identity is just another layer making up the complex and ever-

evolving person I believe I am.