The Traveller: An Ode to Earl Klugh

It is the late 1980s. I’m a child in Tokyo, spending quiet weekday afternoons wandering modern and sparsely populated department stores, whilst my Dad rehearses for his role as ‘Poppa’ in the Japanese production of the musical Starlight Express. I’ve already completed the daily, mandatory requirement of two hours of homework, set by my primary school back in England, and now I’m alone with my mum in a state of childhood bliss, set adrift in a world of Gundam robots, limited edition Transformers and high-tech gadgets that, little do I know now, will still be considered futuristic in the year 2014 (once, in the Toyota factory, I saw the working prototype of a flying car).

This gentle atmosphere – the empty but exciting Japanese department stores, the tender relationship between mother and child, the happy meandering weekday afternoons that, when I look back, will one day make me truly understand the Japanese concept of ‘Mono no Aware’ – has a soundtrack. It has been filling the shopping malls with a tropical lilt for weeks, but my mum and I haven’t really noticed it, because it isn’t designed to be noticed, just to accompany you like an understanding friend who doesn’t talk, just listens.

When our six months living in Japan is drawing to a close, our minds focus. We’re going to miss this place, these moments, and we must remember to take back as much as possible… “The virtue of finding a gilded pavilion in Kyoto”, says Pico Iyer, “is that you get to take back a more lasting, private golden temple to your office” or, in our case, Sheffield terrace house.

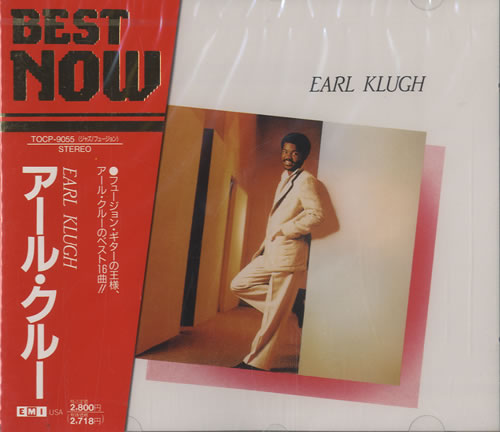

So we notice strange little things we wouldn’t have noticed before, like the mellow quiet storm jazz guitar music that has been keeping us company and had us floating on clouds the whole time. My mum asks a shop assistant who it is, but they don’t know. This is helpful Japan, though, so the shopping assistant asks her supervisor, who doesn’t know either, so the supervisor asks the shop manager, who doesn’t know either, then the manager asks security, who don’t know either, and phones the manager of the shopping centre, who leads us to a room where the music for the shopping mall is controlled. A CD lay at the side of a series of granite-coloured, metal hi-fi separates with loads of buttons on them. On the inlay in the jewel case of the CD there is the photograph of an elegantly but casually dressed black man with a neatly gelled Afro, smiling warmly. The store manager picks it up and reads the name of the artist. “Errr Krue”. He passes it to my mum. “Earl Klugh”.

It is 2014. I have two books to finish, with deadlines, a tax return that is late, at least fifteen E-mails to send, two contributions to Afropean to read, a call to the water board to make, a contract from my literary agent to sign, a change to a direct debit to initiate, and a visit to my dentist to schedule (which I’ve been putting off for months). But everything is fine, because I’m completing these tasks in my own imaginary ‘80s Japanese shopping mall, conjured up by the Jazz guitar of Earl Klugh playing through my iPod dock.

For a Grammy award winning musician whose career spans six decades, in which he has recorded 23 top-selling albums (five of which were number ones), receiving 12 Grammy nominations in the process, there is surprisingly little information about just who Earl Klugh (pronounced Earl Clue) is. But there are a few clues (excuse the pun). We know he was born in Detroit in 1953, and currently runs a very pleasant sounding Jazz weekend retreat at Kiawah Island Golf Resort in South Carolina. But that is about it.

Perhaps that in itself is a telling sign of just who Earl Klugh is: A quiet man who simply wants to share his music with the world. In an era of endless irony (“…it’s kind of, you know, good, but in a shit way… you know, shit, but knows it’s shit, so it’s good” type stuff), social media PR campaigns and reality TV shows, perhaps we can all learn from Earl Klugh’s quiet integrity and his simple, Buddhist-like dedication to mastery. Earl Klugh is a great guitar player, and it’s clear that’s all he is interested in being known as.

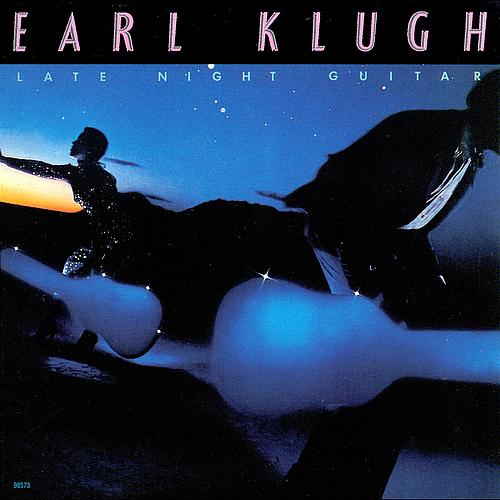

There are those who have reduced Earl Klugh’s contribution to mere ‘elevator music’, and it is true that hotel foyers, office elevators, call waiting machines and, well, shopping malls have all used Klugh’s music voraciously, but that is for a reason. When I hear his music I don’t think of an elevator (…okay technically I do think back to the ‘80s Japanese shopping mall, but not in a mundane way), his is escapist music, and a few strums of his guitar are capable of transforming an elevator into a beach shack, or a lobby into an island paradise. Even his song titles often sound like exotic ‘80s cocktails; Calypso Getaway, Santiago Sunset, Desert Paradise, Jamaican Winds… there are many more. This was middle-class black music for the wide-eyed traveller.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t have to stick up for Earl – Onyx, Nas, Jay Z, 2pac, Mary J Blige, Raekwon, Guru and J Dilla, whose music has all benefited from Earl Klugh samples over the years, can attest to his credibility as an artist. Though his leaning towards the mellow side has fixed him firmly in the Smooth Jazz genre, there is no doubt that he is one of the greatest guitarists of his generation, and the scant biography on his Wikipedia page tells me that Modern Guitar magazine wrote that Klugh is “…considered by many to be one of the finest acoustic guitar players today”.

Contemporary black music has finally managed to shake its moniker of ‘urban’; a genre type that has thankfully begun to sound like a relic of the early naughties. By the ‘90s, it was evident that so-called ‘black music’ was a somewhat clumsy term that didn’t account for some of the great white Soul singers and Hip-Hop artists that had started to emerge, and because most popular forms of black music were ‘of the street’, urban seemed a democratic replacement. Labelling music is always problematic, and when you’d see artists like Erykah Badu in the ‘Urban Music’ category, it begged the question: what is ‘urban’ about Erykah Badu? But the black music artists of my generation do have to take some responsibility for that label; in the ‘90s ‘the street’ was often the first place you’d search for blackness. If you were black and weren’t street, what were you?

It is surprising that Earl Klugh’s sense of escapism never really took hold in Hip-Hop, despite being sampled so heavily. His lilting melodies were often dirtied, and turned into dark stories of crime and death. 2Pac’s ‘Pain’, for example, which samples Klugh’s ‘Living Inside Your Love’, though a brilliant piece of music in itself, is a prime example of this. Representing the street is one thing, but what about music that could help people escape the street for a moment? Whilst so much black music was about ‘keeping it real’ and representing the streets, Earl Klugh’s evocative chord changes seemed to be the sound black people going somewhere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1LXb8RAOtA

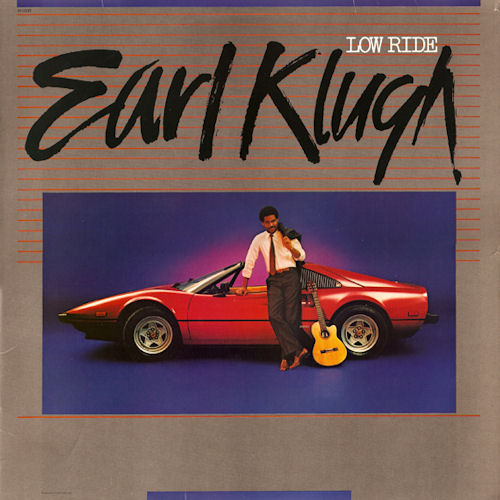

Hip-Hop is my staple, but I lament the fact that it seemed to destroy a more elegant black male identity that had started to emerge in the 1980s. As a young black man growing up in Britain, I remember the pressure people put upon me to be street. Once a beautiful white girl approached me in a club and seemed interested until she asked the question: “are you a drug dealer?” When I said I wasn’t her face dropped. I was poor and black but not dangerous, like the exciting black guys on TV, so what was in it for her?

I might be being a tad romantic, because ‘80s capitalism has a lot to answer for, but for a while, along with Earl Klugh, artists such as Luther Vandross, Bobby McFerrin, Alexander O’Neil, Quincy Jones, James Ingram, Peabo Bryson, Al Jarreau and Gregory Abbot seemed to bring a different kind of blackness to the fore, representing men like my dad; metropolitan professionals interested in seeing the world and mastering a craft; travellers less concerned with ‘swag’ and ‘steez’ and more interested in poise, discretion and etiquette.

In the mid-‘90s the all-to-brief ‘Neo-Soul’ genre came along and seemed to marry the Hip-Hop aesthetic with ‘80s quiet storm elegance (Maxwell, for instance, cites his love of ’80s Jheri-Curl Soul’ as an inspiration), but it wasn’t long before an obsession with all things ‘street’ took over and Neo-Soul artists themselves rebelled against the term. But I can see the ‘Earl Klugh’ aesthetic taking hold again in the younger generation. Perhaps it is globalisation, and the influence of the internet, which allows one to travel the world digitally, but young black kids are rocking so called ‘Cosby Sweaters’, neatly trimmed high tops and making the type of ‘dream-soul’ music Earl Klugh would love. Let’s hope Earl Klugh’s ethos of integrity and mastery over fickle fame and trashy celebrity is also reinstated, along with the wanderlust of this musical traveller.