Triumphant Nubia: Conqueror of Egypt, Intimidator of Assyria, Nemesis of Rome

Written by Robert Fikes, Jr., Emeritus Librarian, San Diego State University

The year was 701 BC. King Sennacherib, the cruel and spiteful ruler of Assyria, later infamous for burning Babylon to the ground, continued his trail of devastation and suffering in Israel until he reached the walls of Jerusalem. His army was poised to make an assault that he must have been confident would result in pillage and slaughter. But suddenly, inexplicably, the terrifying Assyrians departed. Why?

The Bible (II King 19-35) tells us that Hezekiah, the king of Judah, and his people were saved because of a nocturnal visitation by “the Angel of the Lord (who) went forth, and slew 185,000 in the camp of the Assyrians.” The Greek historian Herodotus reported that a plague of rats is what persuaded the would-be butcher of Jerusalem to abandon his project; and the Babylonian writer Berosus asserted that pestilence upended Sennacherib’s plan. But the truth of the matter, supported by recent scholarship, is that Jerusalem was rescued by a young Black Egyptian prince, later a pharaoh, and his mighty army that contained a substantial number of his brethren who sprang from Nubia.

Nearly seven centuries passed. Romans were the new masters of Egypt and they looked south to wring that region for more tax revenue, acquire assorted goods, and gain access to a potentially lucrative trade network. They soon learned Nubia’s Kushite kingdom and their fierce warrior queen did not fear their legions. In the aftermath of incursions made into their territory Nubians responded peremptorily in 25 BC, attacking Roman outposts, enslaving hundreds of enemy soldiers and vandalising statues of their emperor, Caesar Augustus. When Romans retaliated with an invasion, the queen prosecuted the war to a stalemate.

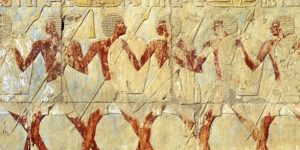

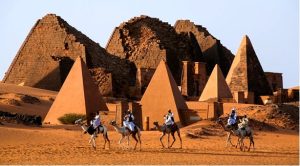

It has long been known by biblical scholars and historians, ignored or concealed by latter-day imperialists, and rarely celebrated or unrecognized by those who could have benefited most from awareness, that highly sophisticated Black Africans once successfully battled and intervened militarily to halt an existential threat posed by three of the greatest superpowers of the ancient world. These extraordinarily resourceful Africans called Nubians inhabited North-Eastern Africa that prospered along the length of the River Nile below Aswan, Egypt, in the nation we know today as Sudan. A distinct geopolitical entity since circa 2,500 BC, it had been referred to by the ancients as the ‘Land of the Bow’ (its archers were famed for their deadly accuracy and service in the armies of Egypt and Persia) and ‘The Land of Gold’, for its mines produced more of the precious metal than any other nation during antiquity. Within Nubia there existed three politically complex Nubian/Kushite kingdoms that rose and fell over 1,400 years with capitals at Kerma, Napata, and Meroë.

Egypt’s Black (Nubian) Pharaohs

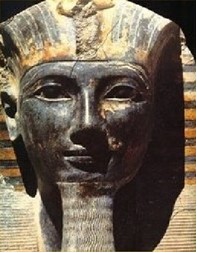

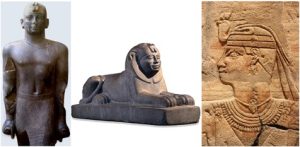

Nubians, whose history intertwine with that of Egypt, actually built more pyramids than their northern neighbours with whom they sometimes intermarried. They both adopted and transformed Egypt’s cultural manifestations. The Kushite King Kastha conquered Upper (southern) Egypt in 750 BC. Five years later his son, Piye (aka Piankhi) led his well-disciplined Kushite army – boasting superior horses, chariots, elephants, archers, and skirmishers – to overwhelm the remainder of Egypt. He established the 25th Dynasty with himself as the first in a succession of five Black pharaohs who ruled Egypt for almost a century. During Piye’s reign, both Lower (northern) and Upper (southern) Egypt were united under his authority. Enthroned at Thebes, the Black pharaohs were politically astute. They re-established stable government, revived state religion, erected monuments and built temples on a grand scale, tried to extend Egypt’s influence in the Near East, and are given credit for generating economic growth.

Taharqa, the fourth of the Black pharaohs, is remembered not only for building temples and pyramids but also for coalescing aspects of Egyptian and Kushite culture. He strategized to frustrate the rising threat of Assyria by forming foreign alliances and winning military campaigns (most consequential his crushing defeat of Assyrian king Esarhaddon in 674 BC). The Old Testament prophet Isaiah recorded that the frightened leaders of Jerusalem sought help from Egypt because they had “trust in the multitude of their chariots and in the great strength of their horsemen” (Isaiah 31:1).

Thus, when Assyrian King Sennacherib, Esarhaddon’s predecessor, convinced he would add to his string of conquests, arrived at the walls of Jerusalem in 701 BC, the then 20-year-old Prince Taharqa’s Egyptian-Kushite army sallied forth for a showdown. To be brief, a chastened Sennacherib blinked – did a timely about-face and left for home – sparing the Hebrew nation catastrophic finality. There remains the possibility that a mysterious plague played a role in Sennacherib’s retreat and that Taharqa may even have faced Sennacherib in combat (the unconfirmed Battle of Eltekeh). The preceding is, essentially, the rigorously studied conclusion of Canadian journalist-historian Henry T. Aubin, whose deep dive into ancient history began when he adopted an African American boy and, hoping to inform him about a proud heritage, began exploring African history. The upshot of a ten-year odyssey of research was an alternative interpretation of a Black-Jewish alliance and legacy that he explained in rather convincing detail in his acclaimed book, published in 2002, titled The Rescue of Jerusalem: The Alliance Between Hebrews and Africans in 701 BC (Anchor).

Aubin’s work is a refreshing corrective to the smug, Eurocentric slant in writings over generations that superficially portrayed Nubia. Too often these writings were dismissive of the capabilities and achievements of this formidable ancient Black civilisation, relegating it to footnote status. Though hardly an attempt at revisionist analysis, the academic community seemed somewhat reluctant to deliver a verdict on Aubin’s assertions, but in 2020 a solid majority of distinguished scholars agreed with his major points in their collected critiques in the book Jerusalem’s Survival, Sennacherib’s Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE: An Examination of Henry Aubin’s Rescue of Jerusalem(Gorgias Press).

The Assyrians eventually ended the line of Black pharaohs but their descendants restored the vitality of their kingdom administered in Meroë. They remained proud and feisty. Herodotus tells us that when spies for Persian King Cambyses II were caught, they were returned with a message from Nubian King Amani-Nataki-Lebte, who criticized Cambyses for not being a “righteous man” because he wished to conquer and enslave people who had not wronged him. He mocked Cambyses and dared him to attack, saying: “The king of the Ethiops (meaning Nubians) thus advises the king of the Persians when the Persians can pull a bow of this strength thus easily, then let him come with an army of superior strength against the long-lived Ethiopians – till then, let him thank the gods that they have not put it into the heart of the sons of the Ethiops to covet countries which do not belong to them.” Such insolent provocation could not stand, so in 524 BC Cambyses led an ill-fated punitive force into northern Nubia that, due to some unforeseen circumstances (poor logistics, desert climate, rebellion), soon had to withdraw before a decisive battle was fought.

When Nubians Clashed With Romans

Unlike the problematic Battle of Eltekeh there is credible evidence that indeed blood was drawn when Kushite armies from Nubia invaded Roman-controlled Egypt in 25 BC.

In 1910, the world of archaeology was stunned when an elegant bronze head of Emperor Augustus, apparently detached from a full body statue, was excavated at the site of Meroë. Naturally, the inescapable question was who brought the head to that faraway ancient capital and why was it buried there?

The suicide of Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the wake of their fleet’s defeat at Actium allowed for the subjugation of Egypt by Rome Augustus. Romans fantasised about Nubian gold and welcomed the prospect of exploiting new markets along trade routes deeper into Africa, where ivory, ebony, exotic beasts, and animal pelts could be acquired. Egypt’s Roman governor, Aelius Gallus, in an extraordinarily short-sighted act of overreach, levied tax on areas traditionally considered in Kush’s realm. This ill-advised measure – probably demanded by officials in Rome – aroused the Kushites who readied for war.

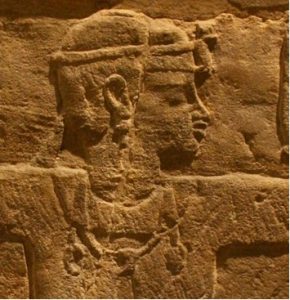

Incensed, the very able Queen Amanirenas, who the Greek geographer-historian Strabo described as “a masculine sort of woman blind in one eye,” rose from the royal family of Kush to lead an army of 30,000 men who crossed a buffer zone into Egypt. Her large expeditionary force overran Philae, Elephantine, and Syene (Aswan) and enslaved their inhabitants and defenders.

Before leaving the battle-front, the queen’s soldiers ruined symbols of Roman dominance, most significantly a statue of Emperor Augustus that was pulled down and decapitated. This aligns with the often-repeated claim that Amanirenas carried a trophy bronze head back to Meroë to have it interred at the entrance to her palace (or the ‘ceremonial path that led to the Altar of Victory’) where people trod. One explanation for why this was done was to insult and show contempt for her supremely cunning foe; another is that Nubians believed that walking over a representation of an adversary diminishes or terminates his power. Both explanations provide a plausible reason as to why the bronze head of Augustus was discovered at Meroë nineteen hundred years later and nineteen hundred miles from whence it had been sculpted and cast.

In retaliation, the Romans sent a punitive force of 11.000 soldiers under Gaius Petronius that reclaimed lost territory, pushed deep into Nubia’s heartland, and destroyed Napata before returning to Egypt with plunder and captives. He thought it unwise to march farther south through more difficult terrain where he would undoubtedly have encountered strong resistance from Queen Amanirenas entrenched in Meroë. After a while the queen regrouped, rallied her fighters, and went north again to retake what was now the Roman garrisoned town of Primnis. Outside its gates Kushites faced off against Romans waiting behind fortifications, anticipating the order to charge. But on this tense occasion diplomacy prevailed.

Having made her point about her people’s willingness to fight to preserve their sovereignty, she sent envoys to parley with Petronius who subsequently had them escorted to the Greek island of Samos where Emperor Augustus cordially received them. An often-recited story (of questionable authenticity) is that one of the envoys presented Augustus a bundle of golden arrows, saying that Queen Amanirenas offered them as a sign of her desire for peace and friendly relations, but that if he rejected her sentiments, he should accept them nonetheless for he would need them in his war against her people.

Both sides had pressing reasons to halt further conflict. An agreement was hammered out wherein Kush would pay tribute to Rome owed before hostilities commenced and compensation for ravaging places in Upper Egypt, while Rome would return Kushite lands taken during war and cease efforts to tax Nubians. Neither the queen’s husband, King Teritegas, nor her son, Prince Akinidad, survived war with the Romans but, henceforth, the grasping tentacles of the far-flung Roman Empire would never again reach into Nubia and its kings and queens would never be compelled to cede land, convey its resources, or pay tribute to Rome. In a new era of mutually beneficial trade Nubia prospered and peace endured, to the extent that during the reign of Emperor Nero a hospitable Nubian king assisted Roman explorers seeking the source of the Nile (they may have traversed as far as Uganda).

Reflections and Legacies

In closing his conference paper, The Invisible Superpower, British scholar Dr. Lewis R. Peake wrote: “Today if one were to approach the average person or even a mainstream historian . . . (and) suggest that 2,700 years ago a Black African (Pharaoh Taharqa) ruled over one of the two largest and most powerful empires on Earth, and for short periods might even have been the most powerful man on the planet . . . the response would likely be one of derision.”

The lack of accurate knowledge about Nubia in English-speaking countries is undeniable and it has been conspicuous in the declarations of the literati. In 1934 Arnold Toynbee, one of the high priests of European history – haughty, insufferable, and perfectly comfortable in his conviction about Black Africans – wrote: “It will be seen that, when we classify Mankind by colour the only primary race that has not made a creative contribution to any civilization is the Black Race.” As late as 1963 another eminent British historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, pontificated with a sneering air of superiority and contempt: “Perhaps in the future there will be some African history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness . . . and darkness is not the subject of history.”

Possibly Toynbee and Trevor-Roper would not have spouted such nonsense had they been reminded that when their ancient ancestors were spiking up their bleached hair with lime and painting themselves blue before running butt naked into battle, and, as recent archaeological evidence confirms, were practicing ritual cannibalism, sub-Saharan Blacks were constructing hundreds of pyramids and three-story palaces; that Nubians were managing complex government bureaucracies, had mastered astronomy thousands of years before Stonehenge; dressed themselves in patterned fabrics; had invented their own unique alphabet; developed an iron industry; and laid their deceased royalty on beds of gold. Trying to explain the kind of cold disdain for humans of a different colour or ethnicity exhibited by privileged, highly educated people like Toynbee, Trevor-Roper, and many others, the American intellectual Ben Hecht remarked: “Prejudice is a symptom that can thrive in the most acute and enlightened minds as it can in the darkened thought of fools.”

Five centuries of conquest, domination, exploitation – slavery in particular – of people on distant continents gave birth to a heretofore unparalleled manifestation of racism, the contours of which would have been alien and incomprehensible in the ancient world. In Homer’s Iliad, Ethiopians (what Greeks and Romans called all Blacks residing south of Egypt) were said to be “blameless,” “loyal, lordly men” whose nation Zeus “and all of the gods went” to feast. Herodotus, who had visited Egypt saw Nubians there thought they were “a mighty race” whose people were “the tallest and most beautiful of mankind”. The Sicilian Diodorus Siculus said Nubians believed their nation was older than Egypt which they considered their colony and “suppose(d) themselves also to be the inventors of divine worship, of festivals, of solemn assemblies, of sacrifices, and every religious practice.” The 4th century Roman commentator Lactantius Placidus mentioned the Black nation’s reputation for having “the most just men and for that reason the gods leave their abode frequently to visit them.”

It can easily be argued that the martial and cultural achievements of ancient Nubians have yet to be emphatically and authoritatively affirmed and imprinted in the public mind mainly because of longstanding disregard – some contend deliberate deception and obfuscation – by those who knew, or should have known the facts of the matter. And one of those obvious facts is that ancient Nubian/Kushite interactions with Egypt, Assyria, and Rome altered the course of history.

Had Taharqa’s army not shown up at the right moment in Judah to ward off Assyrians intent on reducing Jerusalem to ashes, Judaism may not have survived to spawn Christianity and Islam. Egypt might not have experienced a building and cultural renaissance had the 25th Dynasty of Black pharaohs not ruled. Had Queen Amanirenas not checked Roman expansion at Primnis, not only Nubia but also the ascending Kingdom of Axum (Ethiopia and Eritrea), would have been stunted and interior Africa would conceivably be unrecognisable to us today. Hopefully, sometime in the near future Nubian hieroglyphs, to date untranslatable, will be deciphered so that we can better understand from these ancient Blacks how they viewed themselves, their environment, people beyond their borders, and how they accounted for their actions. Until then, we impatiently await more clarity and insight.

Unknown FACTS! If we knew our (REAL) HISTORY and forget about “pushin weight”, every young kid being a superstar rapper or athlete and making babies, etc. If we had UNITY and KNOWLEDGE we’d be a lot better off!