Review: Sizwe Banzi Is Dead

Upon entering the theatre, wooden, hand-painted signs in English and Afrikaans direct whites and non-whites to separate seating areas – a segregation enforced by a burly, white bouncer. It is both bewildering and uncomfortable to watch as theatre-goers realise they are being segregated and yet seem to fall into line completely, with barely a murmur of consternation. Interracial couples come through the barriers in their correct signification before standing uncertainly on the stairs as they realise they aren’t meant to be sitting together. Girls of ambiguous descent shyly move forward, tittering amongst themselves at the absurdity of it all. Rebels steal over to the other section to sit with loved ones. Before the play begins, a police guard walks slowly up and down the stairs, peering at audience members whilst making notes in a little pad, the consequences of which are yet to be known.

Of course this is 21st century South London, not apartheid South Africa, so everyone knows this is part of the premise, this relic of a previous, tyrannical era, when whites and non-whites were forcibly segregated.

The set is made from boards of plywood upon which arbitrary numbers have been sprayed, ornamented with pieces of corrugated iron and centred about a large wooden box. The muted chords of “For What It’s Worth” come through a transistor radio. Suddenly the box is flung open to reveal a smiling black man and a makeshift photography studio, a hand-painted sign reading “Style’s Photographic Studio”.

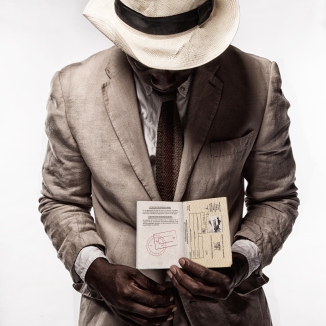

Styles introduces himself and begins to regale his audience with tales of how he came to be proprietor of his studio. In doing so he explores the context of apartheid South Africa, laying the framework for the second act. He calls his studio a “strong room of dreams” and alludes to the myriad ways in which photographs can encapsulate an identity in a land where identities are entrapped in the material nothingness of a passbook – the identity cards non-whites were forced to carry which denied them their freedom of movement and employment.

Soon a man called Robert Zwelinzima comes to the studio wishing to take a photograph to send to his wife back home, and it is through the second act, staged as a flashback, in which we find out how Sizwe Banzi comes to be dead, alongside a present time monologue in the form of a letter to Sizwe’s wife read by Robert.

Sizwe is a man who is trying to feed a wife and four children back home in King Williams Town. He has come to Port Elizabeth to work and yet through bureaucratic enforcement, he is banned from working and must return home. He has three days to report back to King Williams Town, but moving to the house of a friend of a friend – Buntu – together they hatch a plan to ensure that Sizwe Banzi is indeed dead.

How important is one’s name? asks this thought-provoking and emotional play. Steeped in humour yet dealing with a powerful subject, Sizwe Banzi Is Dead was heralded as a beacon of anti-apartheid fervour in 1970s South Africa and London. It cannot be overstated how contemporary the subject matter is in a world in which Palestinians and North Koreans and others are still denied freedom of movement and forced to bow down to the tyranny of the state.

Originally written by Athol Fugard, with the collaboration of actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona, ‘Sizwe Banzi…’ first premiered in Cape Town in 1972. In 1974 after a run at the Royal Court Theatre in Britain, it received the London Theatre Critics Award. Both Kani and Ntshona won Tony awards for their brilliant portrayals in this two-man play. In this contemporary reworking, Tonderai Munyevu and Sibusiso Mamba take up the roles splendidly, imparting on their audience both the desperation and hopes of the protagonists, the sorrow and the humour.

Director Mathew Xia has had a history of involvement with the theatre, first treading the boards at the Theatre Royal Stratford East from the age of 11. He is also well known under the moniker DJ Excalibah, having been part of the BBC 1Xtra team for many years. Winning the Genesis Future Directors Award has allowed Xia to direct this as his first feature length, and it is a commendable choice. It is his hope that young theatre-goers can appreciate this epic script in contemporary times. Although apartheid may be behind us, issues of identity, race and social standing remain pertinent.

Devised by Athol Fugard, John Kani & Winston Ntshona

Cast: Sibusiso Mambo and Tonderai Munyevu

Written by Nat Illumine