Black Travels, Dismantling ‘Fortress’ Europe, 19th Century Tropes and Blurring the Colour Line: An Interview with Igiaba Scego

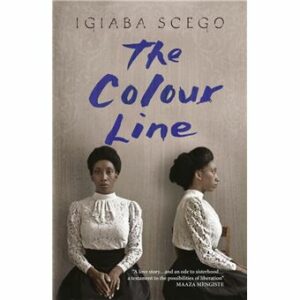

Born and raised in Italy and the daughter of Somali refugees, the multilingual writer, activist and scholar, Igiaba Scego understands very well the complexities of the Afropean identity. 2023 sees the English-language publication of her award-winning book, The Colour Line (Small Axes/Hope Road Publishing). This intriguing and often heart-wrenching historical novel charts the journey of one Lafanu Brown; a half-Haitian, half-Native American artist who, under the aegis of fickle Caucasian benefactors, flees the violence of US racism to seek her fortune in the Italian capital. Brown is a homage to real-life 19th Century African-American pioneers, Sarah Parker Remond and Edmonia Lewis. They made similar definitive transatlantic journeys to Europe, at a time when solo international travel for Black women was virtually unheard of. Scego speaks to Afropean.com about the genesis of The Colour Line, being sensitised to colonialism by her parents, outrage at hierarchical migration policies and a conflicted relationship with her hometown, Rome.

AP: Prior to writing the novel, you had immersed yourself in the history of the African presence in Europe. One source that had special resonance was the anonymous painting, Chafariz d’El Rey. Could you say a little more about the role art played in your research?

IS: When I began to research the novel, I was very interested in the presence of Africans in Europe and the African-European identity. I’m African-European, I’m African-Italian and I’m Somali-Italian. This [carries] a lot of meaning for me. I’m a product of colonisation. In 1970 my parents moved to Italy, which they chose because of the language. It’s strange. Italy is in the centre of the Mediterranean. It’s Europe but it’s [also] the Middle East, it’s Africa…it’s many things all together. Italians only became white [late into] the 20th century. [They were not considered] white at all when they migrated to the US or Brazil, for example. Now, Italians use the word ‘white’ and say ‘we are proud to be Western’, especially politicians and some media. But the story of this country involves the presence of black people as well as Arabs and others. You see it everywhere, especially during the Renaissance. You find a black presence in really famous paintings by Carpaccio and Veronese. There’s also the story of Alessandro de Medici, one of the dukes of Florence, who was black.

[In the novel] I wanted to connect the story of Africa with the story of Europe. I’m involved in that story. I wanted to show that the African presence in Europe isn’t just about recent migration. People here always say ‘We’re not as racist as the US because Italy didn’t enslave anyone’. This is not true. There were different kinds of slavery- not just the transatlantic, middle passage. There are a lot of sculptures [in Italy] with enchained black people. The [so-called Four Moors] fountain in Marino (pictured below), which I used in the novel, greatly impacted me.

AP: In the novel’s acknowledgements, you give a touching tribute to your late father and credit him for sensitising you to colonial history. Growing up, were you aware of other children from similar backgrounds also receiving this kind of input, or was your dad an outlier?

IS: In Somali families, stories are central to education. As in, telling the stories of what happened before; your real background and status. You lose status with migration. My father was a minister for foreign affairs in Somalia. He was an ambassador to the EEC at the time. He lost everything in a day when [Mohamed] Siad Barre came to power. My father tried to re-organise himself, which isn’t easy when you’re in your 50s.

My parents gave me new lenses through which to understand the world. I have another friend who’s the same age and went through similar experiences. Her mother gave her weapons to survive as a minority. Nowadays, diversity in Italy is normal but in the 1970s, 80s and 90s it was quite difficult.

AP: Your protagonist, Lafanu Brown, is an amalgamation of – and yet distinct from – two African-American women who had made Italy their home in the 19th century: midwife and activist Sarah Parker Remond and the sculptor, Edmonia Lewis. Could you explain how you came to know of these trailblazers?

IS: I was aware of Edmonia for a long time. I knew her sculptures, her story and where she’d lived in Rome. It was an Italian friend of mine who sent a picture of Sarah Parker and asked me to write a novel about her. I thought, ‘Oh my god, that’s impossible’. I’m not African-American. I didn’t want to be guilty of cultural appropriation. For that reason, I invented a new character. I wanted to speak about travel between the US and Europe but with a black body.

AP: How did you go about choosing Lafanu’s name and heritage?

IS: Lafanu is a variation on the [sur]name of [Irish] gothic writer [Sheridan Le Fanu]. I chose the name of a horror writer because I wanted to say our lives are hard and we have to live through things that white people don’t. There’s more struggle and fight. But I’m also being ironic. For example, for the modern [counterpart to Lafanu] I chose the name Leila, in honour of a friend who is the only Afrodescendant woman senior academic in all of Italy’s universities. We have a big problem of representation in Italy.

AP: Lafanu’s mixed Black and Native American background seems to be based on that of Lewis but you gave her an Haitian father instead of African-American…

IS: I chose to add Haiti to the story because it was [the location of] the first black revolution. I studied Spanish and Portuguese so I always look to Central and South America out of interest. This Haitian heritage gives Lafanu the energy and power to survive rape and lack of opportunities. By the end of the book she finds her future.

AP: You speak about the Italy of Remond and Lewis’ era being ‘synonymous with welcoming…’. However, it was still a country with imperial ambition, as depicted in the opening chapter of the novel where you describe the country’s defeat in the battle of Dogali. Is this not therefore a rather idealised version of that time?

IS: I don’t believe so. In the early part of Italy’s story as a nation, a lot of people came here to study, or to seek a revolution and so on. Something changed when colonialism entered the frame. The elite of the North wanted to unite Italy but the South, not so much. That’s why people say the South was Italy’s first colony.

I was trying to understand why Edmonia and Sarah chose to live here. I used the trope of the Grand Tour; novels about the Upper Class travelling to Italy, reinventing themselves and their identity. A lot of people came here from the US, England, France, Germany…Goethe and Henry James, for instance. Within this Grand Tour frame, I placed a black woman and of course there’s a power shift.

We tend to fixate on the colonial power [itself] to explain what it is to be a colonialist but within these societies, there are many people against colonialism. Even during the 19th century. To illustrate, I use the figure of Ulisse Barbieri at the beginning of the book. He was an anarchist and wrote poems criticising colonialism. Empire-building is also a mess for the poor and the working class. It’s about exploiting lands overseas but also exploiting the working class internally. The problem is, some people don’t understand the mechanism of colonial power.

AP: You’ve talked about having to ‘unlearn’ everything about Rome, where you were born and raised, when writing the novel. What did this entail?

IS: Rome is a famous city. Everybody knows it. It’s a brand, in a way: The Roman Empire, Julius Caesar and so on. But for me, Rome is like a wedding cake; there are different layers. There’s the Renaissance, Rome in the Middle Ages and, of course, colonial Rome. It’s all around me. You find traces of the [colonial] story all around the city. I wrote a guidebook on colonial Rome and I added some ideas from that to The Colour Line. It’s like what happened with [the] Coulston [statue] in Bristol. We need to decolonise our cities. [To do that] I use my instrument, writing.

AP: The Colour Line is unapologetically political, from its very name, inspired by W.E.B Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk. You are especially vocal about ‘Fortress’ Europe’s racist migration policies. You speak more generally of a global ‘passport Apartheid’ which is embodied – literally – in the harrowing story of Binti. Considering the drift to the Extreme Right by successive Italian administrations, was there a tipping point that made you want to address this so thoroughly in the novel? Was there an autobiographical element to Binti’s story that brought together the political and personal?

IS: The Colour Line was born out of the situation with refugees in the Mediterranean. Through the novel, I wanted to explain in intimate detail both what happens to the body during travel and the right to mobility that all people deserve. For a lot of non-white people, your passport is rubbish. It depends on whether your country is powerful or not. Because of my Somalian-ess – what they call Somalinimo, in Italian – I take the side of refugees. My parents were refugees. It’s a nonsense to obligate people to pay smugglers and put their lives in danger to come to Europe. I wrote this book for that reason. Of course, I’m not a politician. I can’t do anything [on a policy level] but I can convince people here in Italy. It’s the main border of Europe. In Italy, even the Left sometimes uses the same code of ‘security’ as the Far-Right. Immigration is always [framed] as a security problem. The language used against migrant bodies, and above all black bodies, is Orwellian. For that reason I created the characters of Leila and Binti. It’s not autobiographical but I saw this kind of relationship in the [Somali] community. We are a Diaspora. Smugglers blackmail families in the [origin] country and in the Diaspora for money. One person trying to escape bad conditions means a group of people also suffer. It’s the middle/lower-middle class who have the possibility to move. For the poor, it’s impossible to find that money.

We need Europeans to raise their voices to demand a change in the framing of migrants [from the Global South]. The problem is not the numbers arriving. I have a lot of friends in Somalia who would rather go to South Korea than France or Germany, for example. What they want is a passport; the freedom to move. We live in a crazy world of borders, borders, borders and security, security, security. I’m trying to improve the discussion with my novels and by doing school visits to equip the new generation with knowledge.

AP: One of the most frustrating characters in the novel is the Italian/Ghanaian/Nigerian artist, Uarda who, in the name of Pan-Africanism, opts for a conflated and reductive definition of ‘blackness’ that dismisses cultural nuance. Is this representative of many Afro-Italians?

IS: I think so, yes. There are Afro-Italians who are confused about their identity. When I was growing up, I had no concept of being African. I identified more with my city; as Roman-Somali. That’s quite a strong identity in me. Identity is a struggle for anyone in Italy. In this strange unification of the country, we are so different. Sometimes we only become Italian when there’s an international football match. The problem we have as second-generation [African migrants] in Italy is one of citizenship. When you reach 18, you become a foreigner in your own country. This breaks your heart and soul. For people born here like me, you have to complete many documents to obtain your citizenship. It creates a half-identity and thus you try and find it elsewhere. For many years, Afrodescendants in Italy looked to African-Americans. That was the only pillar we had. We began to read Malcolm X, bell hooks, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin – whom I love – and tried to create a pantheon. Eventually, we came to understand we needed to create our own identity as African-European.

For that reason, sometimes second generation [African migrants] lump everything together. There’s a lot of confusion depending on your background. We come from different parts of Africa too; West and East. So in Italy, in terms of politics and the problems of citizenship, we live ‘in-between’. A Far-Right government is not the only problem for me. It’s also the tokenism of the Left. Politicians do not see us. We’re here as a body but no-one speaks to us and our problems. Lack of representation is one of the layers.

AP: It’s funny you should bring up the issue of representation again, as that was the next question. You’ve said that ‘as an adolescent, models help keep you from going under’. What would you say is the state of play when it comes to representation for Afrodescendant teens today, compared to when you were growing up? Does it change depending on where you travel?

IS: I think the situation is a little better in literature. Publishers are smarter than those working, say, in cinema. It’s easier to get into the world of literature. Otherwise, I think the situation with representation is horrible. It has changed a little through platforms such as Instagram because it’s the users who create [content] but the mainstream [in Italy] is awful. For example, if discussing second generation migration or even the Israel-Palestine war, it’s an all-white panel talking about it, always. In cinema, Italian movies are so white. What happened here? Why is knowledge and art only white in Italy?

We need better representation; not only in art, but academia. Nowadays there are many people of all backgrounds who have skills to contribute but nobody asks us. Sometimes they deny the diversity of the country. If you go out in my area there are many people from all over the world; Peru, Bangladesh, Egypt, Ghana…It’s crazy that this is not represented in art. As for the police, after George Floyd and BLM things improved a little bit…

AP…But Italy has had its own George Floyd-like incidents, such as the horrific case last year of Nigerian immigrant, Alika Ogorchukwu…

IS: He’s not the only one. In 1979 a Somali man was burned in one of the main squares in Rome. There are lots of people who have died because of racism in Italy. Nobody does anything about it. Story is important. It’s why I and many other Afrodescendant writers – mostly women – try to uncover these stories and speak about what went before. Outside of Italy, I think it’s a bit better. I spent two months in North Carolina at Duke University. It’s so diverse.

AP: There’s an element of the ‘saviour’ trope in Lafanu’s main love interests, Ulisse Barbieri and Frederick Bailey, based on Frederick Douglass. Were you conscious of any such tension between the novel’s feminist slant and these depictions of male ‘rescuers’?

IS: Yeah, but this is a Victorian novel. Sometimes I used those kinds of tropes. When I started writing the novel, I read a lot of 18th and 19th century novels with white protagonists by James, Edith Wharton and Jane Austen. The thing I love about Austen is the role money plays in her work; connections, the possession of land and a ‘name’… Her books are very useful for understanding Capitalism, Colonialism and the situation of women in that era. Lafanu attempts to survive the problems of a male world – because it is a male world. With the novel, I wanted gradually to create something that was different. I tried and I hope it worked.

AP: So it’s satirical, in a way? – Of course. The only character who is not satirical is Ulisse Barbieri.

AP: Do you speak any indigenous languages?

IS: Yes, I use the Somali language in my new novel, Cassandra a Mogadiscio, published in February 2023. It’s about war, drama, the Somali and Italian languages… Sometimes you need to approach your origins in a different way. The Colour Line gave me the courage to do that.

AP: What is your relationship like with the English language? How involved were you in the Italian to English translation of The Colour Line? There are two translators and there’s a notable qualitative difference between the first and second half of the text, for example…

IS: It’s so sad. The original translator, John Cullen died so a second translator was brought in to continue his work. I wasn’t involved in the translation myself for many reasons. For my new book, I’ve asked an African-American friend to translate it into English. She knows Italian very well.

As for my relationship with the English language, now it’s better. My father lived through different kinds of colonialism. He learned English through his exposure to the British army. If there was trouble in the house, he used English (laughs). ‘Oh-oh, there’s a problem. He’s speaking English today’. For him it was the language of colonialism. For many years, I refused to speak English at all. Then little by little – thanks to Malcolm X, Toni Morrison and James Baldwin – I decided you can choose your [own] English. I try to practise and watch movies because it’s not my mother-tongue. It’s easier for me to speak Portuguese, Spanish and even Arabic. Now my relationship with English is wonderful. That’s why I want a good translation of my work and also to be involved in it. Since it’s an intimate story about my family, I sought another black woman’s involvement.

AP: In the Author’s Note of The Colour Line, you write that ‘Rome has become a city from which to escape [and] not to go back to. It repels both citizens and foreigners’. You remain in Rome, although seemingly disillusioned. You speak several languages and could live anywhere. What keeps you attached to the city?

IS: Everybody asks me that. I love Rome! It’s a contradiction. A professor who knew me deeply once said ‘If you leave Rome, you’ll only ever be able to write a single line’. Rome is my inspiration. It’s my city. I know it by heart. I want to try and decolonise the story of the city. I’m based in Rome but I’d still like to travel all over the world. I’m preparing to go to Brazil next year, for instance. But in the end, Rome is my home. I need to have a base where my family knows they can come and visit me.

This is an edited version of an interview that first appeared on the blog, I Was Just Thinking…