Life in The Hinterlands; Growing up Gay & Mixed Race on The Isle of White

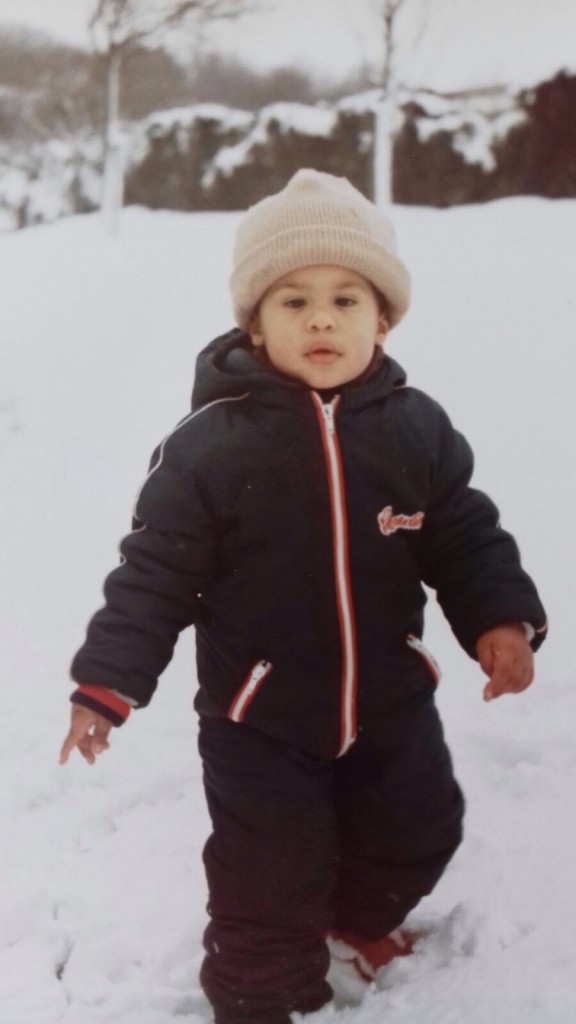

By Ashley Thomas

Life as a mixed gay man seems a singular experience.

Who, what and where are the fluid foundations on which I’m constructed, construed and constrained. To some I am black but not Black, clearly not white or not Black enough. To others, I am an undecided shade of, well, I suppose you might say…

…Brown?

The Isle of Wight is a brilliant homophone. With its crumbling chalk and its crumbling people, it’s REALLY FUCKING WHITE. It’s located somewhere between the English south coast and 27 years ago. The island could seem blank or barren, but this is no creative backwater. At best, rural seaside racism is imaginative: I admired coconut-kicker most for its tropical rhythm.

“What did you say?” In the kitchen one day, my dad was surprised when he found me singing “Eeny meeny miny mo, catch a nigger by his toe.” I didn’t know I was singing about myself. I sang this song with my school-friends but he didn’t tell me what it was that we had said.

He did say was that my skin was Something I Needed To Know About. My sister and I were sat in front of miserable BBC2 programmes about slaves, race riots and the Windrush. Through serious English whitesplaining, I sat through a domestic campaign of Black history and Roots and Jamaican music. On the one hand, I quite liked being different. But Blackness itself required really hard homework and white teachers. I didn’t feel Black. Or at least as Black as I should be.

But sounding or appearing or actually Being Black felt off limits. Even my first name felt like racial misdirection. Through her ex-colonial hardship, mum drummed her fears of a hostile future into her half-Jamaican children. We were taken to karate to defend ourselves. We learned piano to better ourselves. We made sure adults saw we could behave ourselves. We could never get in trouble for standing up for ourselves. Not Being Black was really tiring and, after a while, REALLY FUCKING BORING.

I had my first existential crisis at age eight in my friend’s dad’s 1991 executive white Ford Sierra when I was startled by the big, bold question: “Why are you brown?”

My frozen lack of response was very appropriate and, I suppose, really rather…

…British?

I often walked home from school through the council estate next to our house. One day a girl with neither haircut nor shampoo stood yelling from her shoddy patch of poor dead grass:

“PAKI!”

Accuracy was not her primary ambition. She specialised in the brand of racism that has scant regard for geography. She flogged my skin and flayed my confidence. She later discovered that my maroon blazer and matching cap with yellow shirt and charcoal shorts meant I attended the nearby private school my parents couldn’t afford. She tried lashing me with “PRIVATE!” but it only made a little mark. My meticulous way with words beat her angered estrangement from the letter T.

In contrast to council estates, private schools help children make early acquaintance with meter, prose and metaphor. This was my parents’ hard-earned way of avoiding the racism of state playgrounds in the ‘80s. Nevertheless, an Afro teamed with a maroon blazer, sparkling reading ability and a preference for playing with girls straight up smashed the race, class and gender rules that children innately know. Coconut-kicker was the almost inevitable outcome of a better education.

By phone I’m white, British and middle class. A Londoner maybe. Definitely educated and probably called Oliver. An accent they can’t place on a black baritone that blends with feminine cadences. Physically, I’m often mistaken for half-Asian. Occasionally when my broad shoulders, thick thighs and big belly are accounted for, the answer is Samoan. But my beard suggests I have a relationship with the Quran, certainly when it comes to airports in Southend, Stockholm and San Francisco.

So I feel the double-take when people meet me for the first time.

“Oh!” they will say. “I had no idea you were…”

…Gay?

An emotionally intelligent boy, I collected friends, tools and strategies that helped me survive my iconic attachments to Mariah Carey and heavyweight, bearish men.

I remember a warm summer day, dragging the hose over the lawn to water the overgrowing greenhouses and vegetable beds. I danced along to a cheap battery radio blaring a local commercial station. I imagine the song was Love Will Save The Day by Whitney Houston. Mum threw me a look and a stone-cold sucker-punch: “Stop it,” she warned. “People will think you’re a homosexual.”

I first found God in the form of dark handlebars, a roaring Trans-Am and soft-bellied brawn. Around the age of six, I would sit on an old bar stool drinking a carton of pineapple Just Juice at a place called the Fitness Factory. I watched him work out whilst my dad and sister did karate in the adjoining dojo. Every Saturday, I looked forward to his sweat-soaked singlet, fat-marbled muscles and supremely macho ‘80s hair. When I was dragged off and thrown in the dojo, I literally could have died.

Hell had reserved a special place for me. We ran out of money for private school and I found myself brown, gay and unbaptised. In a Catholic school. On a big white rock. School was run by nuns who were nothing like my favourite ode to religious isolation and repression, Powell & Pressburger’s Black Narcissus. Just like Sister Clodagh’s rival, the REALLY FUCKING CRAZY Sister Ruth, I mastered secrecy and obsession. I eluded everybody, nobody and eventually only myself. (Though I haven’t yet tried to throw someone off a bell tower.) Iconography, rosaries and verses hinted that my unsayable secret was one to keep at all costs.

Coming out is sold as a sort of coming home but, early on, I found the wrong gay neighbourhood. In the streets of Soho, the bars in Le Marais or the bear beach in Sitges, beauty is about the codification and exemplification of a type. We are not interested in the average or the outlier. Embodying and amplifying the social and sexual qualities of the men around you defines that which also makes you…

…Male?

A life on the outside is hard to learn yet richer to claim. There are no maps or guides or well-worn routes, no footsteps for a gay Afropean to follow.

I arrived on the frontiers of adulthood. I explored boundaries and found intersections. I discovered strength in ambiguity and plurality, virtues I would never now trade for a linear lifeline and a never-questioned identity.

In the hinterlands, I became the architect of my own masculinity, blending race, place and space. These are the gifts of this life apart; to disarm and engage; to delight and confound; to question and connect.

The singular experience never exists.