Black and Belgian: Navigating Multiracial Identities in Ghent, Belgium

By Walter Thompson-Hernandez

Introduction

What does it mean to be Black and multiracial in Belgium? How does sub-Saharan African culture and experiences impact the lives of multiracial people or Afropeans in Belgium? How influential is the U.S. Black experience in the formation of an Afropean identity rooted in Belgian and African cultures? These were some of the questions that I pondered, seven weeks ago, at the outset of this project – eight weeks later, I am still grappling with them. This past summer, I arrived in Ghent, Belgium – a city with a population of 100,000 people, located forty-five miles northwest of Brussels – with hopes of understanding and delving into the multiracial experience of five people with parents from a sub-Saharan African country and the Flanders region in Belgium. Through interviews, observational data, photography, and other methods, I compiled valuable information regarding their stories.

Motives

I was drawn to Belgium for various reasons. As the son of an African American father and a first generation immigrant mother from Mexico, I have always been intrigued by the ways in which immigrant-origin populations impact the racial and social fabric of receiving sites. In attempting to construct my own multiethnic and multilingual identity, I have navigated, and often struggled, to understand my role in my family and community, and the subsequent reactions of my relatives – on both sides of the border, on both sides of my family tree. In Belgium, I found similar experiences with people who had at least one parent from an African country. The feelings of marginalization that I came across were all too familiar: ‘People didn’t know how to treat me’ and ‘I felt like I didn’t belong in either Belgium or Africa’ were some of the feelings that were expressed. Often, as I learned, my respondent’s relatives were faced with the challenges of conceptualizing both an African heritage and a Belgian identity. For many of these relatives, as I was told, the idea of a Belgian identity was already complicated by the French-Dutch language divide manifested in the Wallonia and Flanders regions in Belgium. ‘Identity in Belgium is already complicated,’ one person told me. ‘Are we French speaking or are we Dutch speaking? You add race and national origin to that and it really makes things interesting.’ As opposed to many societies around the world, many regions in Belgium, exercise – amidst contentious debate – a French and Dutch multilingual reality that, often, exacerbates identity formation for people of multiracial backgrounds, so that not only does an Afropean, in the spirit of W.E.B. Dubois, have to navigate a “double consciousness” of being European and African, but also split identities pertaining to language.

Secondly, in the age of European “Super Diversity” – a term coined by social scientists to describe the high rates of immigrant inflows to European nations – I was curious about the ways in which second generation children (the children of first-generation immigrants) were constructing their identities in the context of shifting racial and demographic landscapes. In the United States, interracial mixing is, often, romanticized and harmonized in the framework of multicultural ideas dating back to the 1970s. While once seen as a social and racial aberration, evidenced by anti-miscegenation laws and eugenics, multiracial children and families today have in many regions in the U.S. become a normative aspect of society. In Belgium, however, I learned of tacit and explicit “rules and regulations” for interracial mixing.

Religion, in addition to economic and class demarcations, were the factors impeding and sustaining most interracial relationships in Belgium. Muslim populations throughout Belgium – primarily of Moroccan, Turkish, and Tunisian descent – displayed the lowest rates of interracial mixing with white Belgians due primarily to differences in social and cultural practices such as alcohol consumption, language and religious practices. ‘Many people of Muslim descent in this country do not drink alcohol or take part in social experiences that other immigrant-origin groups and Belgians take part in. Whereas most sub-Saharan African people do. They drink beer, go out at night, and that’s important in Belgian for social reasons,’ I was told by an integration researcher. ‘Drinking beer in this country brings people together and provides spaces to mingle, and interact, which, essentially, makes it easier to integrate into Belgian society – and, of course, interracial mixing is one product of that.’

Lastly, as an immigration and race scholar who has primarily focused his work on the experiences of Latin American immigrant inflows into U.S. regional contexts, I was drawn by the opportunity to expand my general understanding of the intersection of immigration and race from an African and European framework. Particularly, I wanted to learn how Afropeans were being integrated into the national narrative. Like the U.S., Belgium, since the 1950s, has been a thriving receiving society for immigrant-origin populations from disparate regions of the world because of guest worker programs, social programs such as healthcare and housing assistance, family reunification laws, and a colonial past. As a result, Belgium’s political, social, and racial fabric has been continually reshaped and rewoven.

Who Are They?

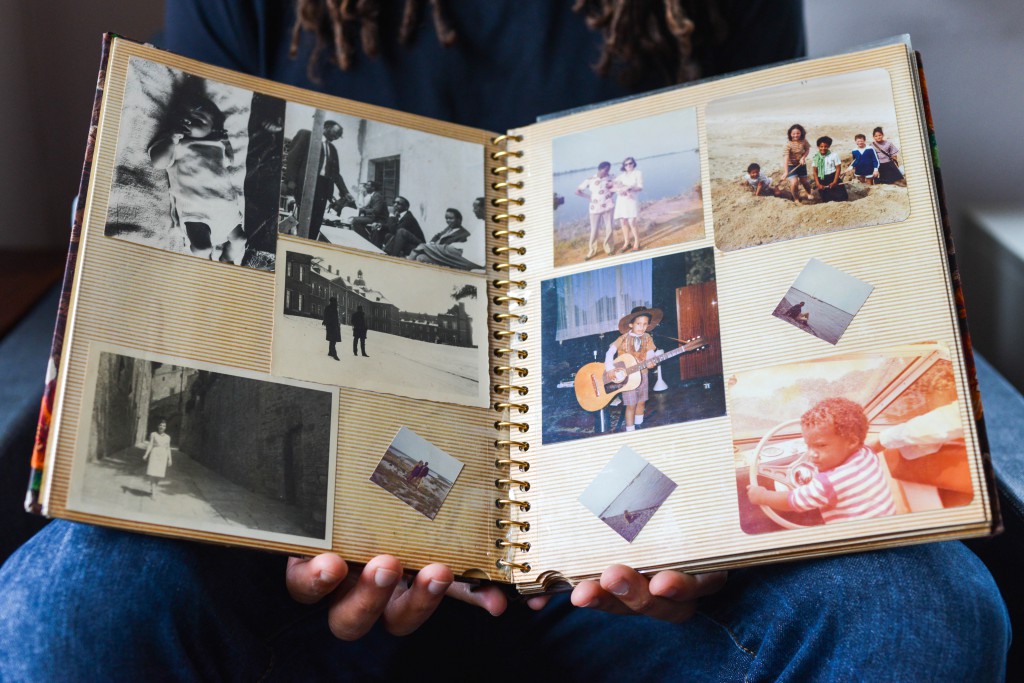

The people in these photos are the children of one first-generation African immigrant and a native Belgian from Flanders. While choosing to withhold their names for the purpose of anonymity, I have chosen to present their photographs as the founding premise of this project. Their stories and experiences are intertwined with their Belgian upbringings as well as their family’s migration experiences from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Sudan, Egypt, and Rwanda. Nearly everyone I spoke to addressed the importance of asserting their “Black” identity throughout their lives in the context of ethnic and racial discrimination, isolation, and a predominantly “white” Belgian society. Those who took part in this project ranged between the ages of 21 to 42. Yet, each person invariably spoke about being “the only one” in many circumstances. “The only one” symbolized being the only Black or Afropean throughout their lives and in different contexts. These feelings of isolation were slightly quelled by their strong connection to their African heritage and identity, however. Thus, I asked: How did having a tangible and viable connection to your African heritage impact the construction of your Black, multiracial, or Afropean identity? ‘Yes, I’m Belgian,’ one person told me. ‘But, because I’ve been to Africa, speak the language, and have a relationship with my relatives there, it makes it easier to fight any forms of discrimination, isolation, or racism that I face here, you know? When I here racist things, it’s funny to me because I know that what I’m hearing is not true – it’s based on stereotypes which aren’t based in facts. And I know this because I’ve been to Africa several times.’

Stereotypes founded on misperceptions rather than empirics were at the heart of their concerns. And statements like these compelled me to juxtapose the existing relationship between U.S. Black Americans, Africa, and identity formation. Was it easier for my respondents in Belgium – as a result of their direct connection to Africa – to combat personal and systemic racism? And, thus, did it make it more challenging to embrace a Belgian identity? It appeared that having a strong and tangible connection to their African cultural heritage helped to combat racism, but, ultimately, as I was told, the U.S. Black experience with racism was often used as a reference point for their own identities.

The U.S. Black Experience

Both the reconciliation and adoption of the U.S. Black experience proved to be both beneficial and problematic. ‘The U.S. Black experience has helped Black people around the world deal with discrimination. Hip Hop music, groups like Public Enemy, helped me a lot. I knew I wasn’t in this alone.’ Others spoke about similar feelings of solidarity. ‘I remember the first time I watched MTV rap videos, man, I was like, yes, wow, those are my people! There were Black people on the television screen who kind of looked like me. That was a powerful moment because before that I hadn’t really seen Black figures on T.V. I was used to seeing a lot of white Belgians.’ One respondent, however, narrated an experience related to U.S. Black history, which triggered negative and frightening memories. ‘When I was a teenager I remember biking in my hometown one day and these four (white) guys started chasing me in their car. They eventually caught up to me and dragged me off of my bike, and in that moment I suddenly thought they were going to lynch me. Why did I think this? I had just watched a U.S. movie about lynching during the 1960s civil rights movement in Mississippi and it was terrifying. So at that moment I thought because I was Black and because that had happened to Black people, that I was going to die in that way as well. Later on I asked myself: Were they chasing me because I was Black? Or would they have chased anyone who would have been in my position?’ Although assuming that the U.S. Black experience provides only positive or negative feelings for people in Belgian with Black and African heritage is reductive, understanding this person’s ideas about his attackers, his racial identity, and the history of lynching and racism in the U.S. illustrates the transnational reality and complexities of Black identity.

Artistic Vision

I advised each person to hold their photographs in a way that could represent their story – or stories. For some, it was the first time they had ever been asked questions about how their parents met or how they self-identified. Others have dedicated their lives to researching their family history, and had published articles and created documentaries on the subject of multiracial identity in Belgium. Most chose to hold each photo close to their bodies, proudly, and intimately. Holding the photos in each palm, in my estimation, shows us the salience of multiracialism. Through these photos we are exposed to a series of faces, emotions, and colors, and it is our job to piece their experiences together, and, in the process, we are naturally inclined to ruminate over the experiences that have outlined their lives. How and where did their parents meet? Where were these photos taken? The hope of this project was not only to show the beauty of these unions, but also the physical, emotional, and psychological barriers and divisions that multiracial people and families navigate through. Some of the people in the photos are still together, others have separated, but what remains is the reality that a connection and bridge was once forged between two people, between two continents, between two worlds.

Reflexivity

As a researcher from the United States, I was reflexive about my position amid my respondents, and the personal subjectivity and academic framework that I have acquired – one almost entirely based on the U.S. Black and multiracial experience. My understanding of “blackness” as a social, cultural, and political signifier – although often spoken through a pan-African lens – is not entirely applicable to the Belgian racial framework. Belgium’s whiteness and blackness are based on hierarchies that took place, primarily, in the Congo – in contrast to the U.S. Black-white racial experience. Additionally, Belgium’s Black populations exist almost entirely as a result of recent immigration inflows beginning in the 1950s, which brings the element of immigration to the fore, so that discrimination and xenophobia faced by Black people in Belgium are potentially rooted in both anti-Black and anti-immigrant attitudes.

It is often the case that U.S. researchers consciously or subconsciously superimpose U.S. theoretical models to social contexts around the world. This I have found to be problematic, and can limit the potential and viability of research projects. The U.S. understanding of race is rooted in U.S. taxonomies lived through the inception of the transatlantic slave trade, Jim Crow laws, and the modern-day explicit and implicit realities of racism. As a result of these enumerated factors, it was often challenging to process the racial and ethnic dynamics, which I encountered throughout Belgium. When creating contacts for my project, I spoke, rather naively, about wishing to speak to people who were “half-black” and “half-white” – as a result, I was often met with blank stares. Because although white and black has been understood to symbolize people of darker and lighter skin hues, in most parts in the world, people in Belgium, if considered to be “ethnic” or non-white, tend to be characterized by their country of origin and not their race, i.e., Congolese-origin, Turkish-origin, and Moroccan-origin. In the same vein, whiteness is something that is understood in an entirely different capacity. When speaking about white racial status or whiteness, I was, again, confronted with the reality that to understand the Belgian, Black, and Afropean experience, I had to adjust my vantage point to mirror Belgian racial and ethnic realities.

What Can We Learn?

While this project might ostensibly appear to create distinction rather than commonality, understanding nuances in the Belgian context vis-à-vis immigration and racial identity ultimately brings us closer to understanding the experiences of multiracial people within U.S. borders – particularly those with at least one parent of immigrant-origin. Immigrant-origin populations and multiracial people experience marginality in both Belgium and the U.S. – systemically and in their personal lives. The feeling of liminality and exclusion creates impediments, which disconnect individuals and groups to larger societal and national narratives. Delving into the genesis of these inequities can, in many instances, help to combat marginalization. In essence, helping to integrate all people in society with immigrant, non-immigrant, and multiracial backgrounds. How well this is accomplished is entirely incumbent on how well the immigrant experience is understood – both in receiving and sending contexts. Partly, there is the realization that immigration is a multifaceted process, which brings about intended and unintended changes to receiving societies. As we transition further into the 21st century, there are searing realities emanating from our nations’ historical treatment of non-white, ethnic and racial groups. The rise of multiracial children and unions, ostensibly, paints a picture of “new age” racial harmony and understanding. However, there are questions, which need to be addressed moving forward: How is the U.S. going to address the concerns of this growing multiracial population? And, is this country ready to conceptualize race and immigration together, and move beyond black-white dichotomies? Failing to take these questions into account will not only negatively impact individuals of multiracial backgrounds, but also people of all ethnic and racial identifications who have the capacities to contribute to the political, social, and racial potential that the U.S. prides itself on.

I think Belgium assumes all “black” is either from the States or from Africa or the Caribbean. They seem to think that Polynesia “doesn’t exist” or that it’s “America,” (It’s the South Pacific between the Equator and NEW ZEALAND) and they sure as hell can’t acknowledge that France’s DOM-TOM isn’t “Africa” or “America” either. I mean, they’re racist as hell but also too THICK to really “blame” them. They’re used to all “blacks” being “foreigners” who “need visas” to be here because Belgium’s former colonials aren’t entitled to Belgian passports like France’s are. They can’t get that I’m FRENCH. Not African or “American.” I’m tempted to try Luxembourg but there’s less to apply for there. But at least there I’d be dealing with both languages I”m literate in. (No Dutch).